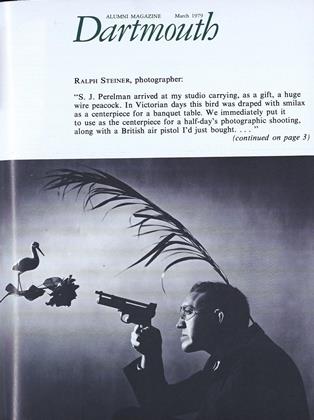

Ralph Steiner '21 is a photographer. If he were more brash, he says, he would also be a psalmist. Actually, he has been plying both trades for 60 years or so. These picture and the accompanying commentaries were selected from a current exhibition at Hopkins Center, where Steiner is artist-in-residence and where, with students and friends last month, he cut up his 80th birthday

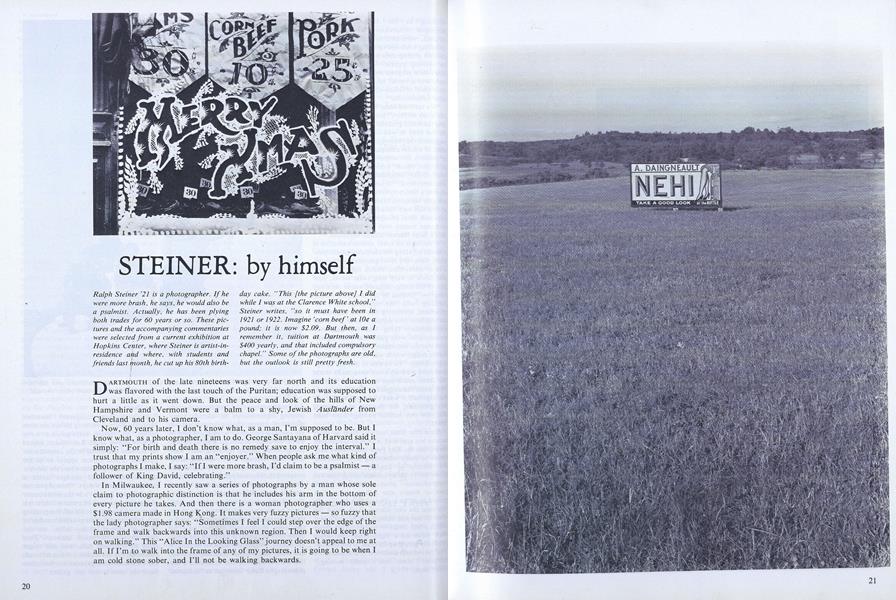

cake. "This [the picture above] I didwhile I was at the Clarence White school,"Steiner writes, "so it must have been in1921 or 1922. Imagine 'corn beef' at 10e apound; it is now $2.09. But then, as Iremember it, tuition at Dartmouth was$4OO yearly, and that included compulsorychapel." Some of the photographs are old,but the outlook is still pretty fresh.

DARTMOUTH of the late nineteens was very far north and its education was flavored with the last touch of the Puritan; education was supposed to hurt a little as it went down. But the peace and look of the hills of New Hampshire and Vermont were a balm to a shy, Jewish Ausländer from Cleveland and to his camera.

Now, 60 years later, I don't know what, as a man, I'm supposed to be. But I know what, as a photographer, I am to do. George Santayana of Harvard said it simply: "For birth and death there is no remedy save to enjoy the interval." I trust that my prints show I am an "enjoyer." When people ask me what kind of photographs I make, I say: "If I were more brash, I'd claim to be a psalmist - a follower of King David, celebrating."

In Milwaukee, I recently saw a series of photographs by a man whose sole claim to photographic distinction is that he includes his arm in the bottom of every picture he takes. And then there is a woman photographer who uses a $1.98 camera made in Hong Kong. It makes very fuzzy pictures - so fuzzy that the lady photographer says: "Sometimes I feel I could step over the edge of the frame and walk backwards into this unknown region. Then I would keep right on walking." This "Alice In the Looking Glass" journey doesn't appeal to me at all. If I'm to walk into the frame of any of my pictures, it is going to be when I am cold stone sober, and I'll not be walking backwards.

THOREAU observed that "Most men lead lives of quiet desperation." During my decades of using my camera to do advertising photography, my despair was hardly quiet; anyone within three New York City blocks could have heard my bitter complaints that my brains were turning to mush and my digestion to a torture from Dante's inner circle.

On the other hand, photographing for magazines and for public relations was far less destructive although it paid far less well. Often it could be challenging and sometimes I could add a tablespoon of humor to the recipe.

The man sitting amidst the black and white spaghetti needed a lot of persuasion to move from the machine where he made floor mops into the middle of his floor mop material. The photograph was rejected by the client because it had no sales compulsion. Some clients don't know when good fortune smiles upon them. If, during my earning-a-living years I'd paid full attention to what my clients told me they wanted, I'd have filled my darkroom right up to the ceiling with highly logical and highly boring pictures.

As subjects there are some things which remain obstinately themselves regardless of who photographs them - mountains, perhaps, stay put more than most things. Not even the most sentimental photographer could transform the grim, deathdealing Eiger into a Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. But a human being, as subject for a photographer, can be anything under the sun or anything under the photographer's lights. If the famous Karsh photographs a man, he turns into a bronze statue on the public square. If Arnold Newman snaps him, he becomes an element in an abstract design. And Richard Avedon portrays almost everyone as having died in a mental hospital and having been dug up two months after the poorest of embalming jobs.

I try my level best to photograph people so they are not responding to my camera but to a human situation. Sometimes I win and often I lose.

LATE one afternoon of the summer when I was earning my Ph.D. in making printable negatives, I saw, as the sun was going down over the horizon, this rocking chair and its shadow on the clapboard wall. No one in the world's history ever set up a huge, cumbersome 8 x 10 camera and snapped the shutter as fast as I did. There was not time to make another negative as a safety measure. Ten seconds later the shadow had dimmed on the wall.

This picture, labeled by someone at the Museum of Modern Art "American Rural Baroque," has been reproduced so often that many people think it is the only picture I've ever made.

THIS was another of the photographs made to satisfy my school-of-photography design teacher. I couldn't afford lenses for my British Full Plate (8½ x 6½) camera, so I mounted single, spectacle lenses in cardboard tubes. I used baking tins from the 5-and-10 store as reflectors for my light bulbs. The exposure at around f. 128 was more than an hour, and by the end, smoke was rising from the overheated typewriter. It never worked very well after having its portrait made. I guess bread toasts better than typewriters.

IN the teens and twenties when I began photographing, art critics, painters and photographers furrowed their brows with "is photography art?" After all, a painting came to life from a man's hand while a photograph was born of a mindless and soul-less machine.

The great and awesome Alfred Stieglitz answered the question in perhaps the only simple statement he ever made: "I prefer some paintings to most photographs. I prefer some photographs to most paintings."

Words can be weapons. Stieglitz left the question flat on the floor; never again to rise. I hope.

IT was about two months ago that an interviewer asked me: "What photographers influenced your work and what do you feel is the ambience in which you work?"

Those are not questions; they are blows to the head with a meattenderizing hammer. My first tendency was to deflate the question and the questioner with a bad pun, and fortunately one came to my rescue — as bad a pun as I've ever manufactured: An ambience is the conveyance which takes you to the hospital when you break your leg." But the tape was for Vermont Public Radio, which gives us joyful Baroque music at breakfast, so I held the pun in - where it still, most likely, festers.

These days I think the composers of music influence me more than any photographers or visual creators. I see something exciting or lovely and think to myself: "If Papa Haydn or Wolfgang Amadeus or the red-headed Vivaldi were here with a camera, they'd snap a picture of what's in front of me." So I take the picture for them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

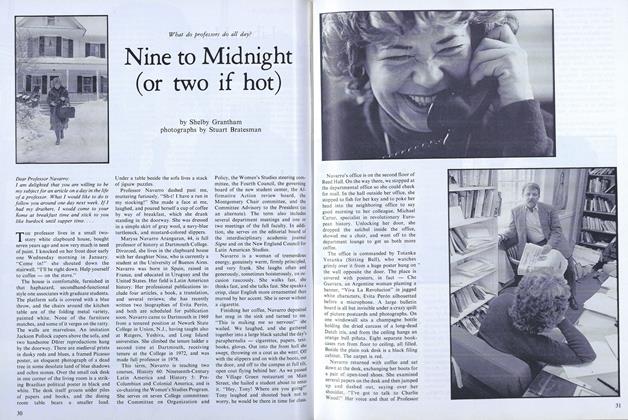

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Article

ArticleWinter Carnival Blues

March 1979 By Biĺ Conway '79 -

Article

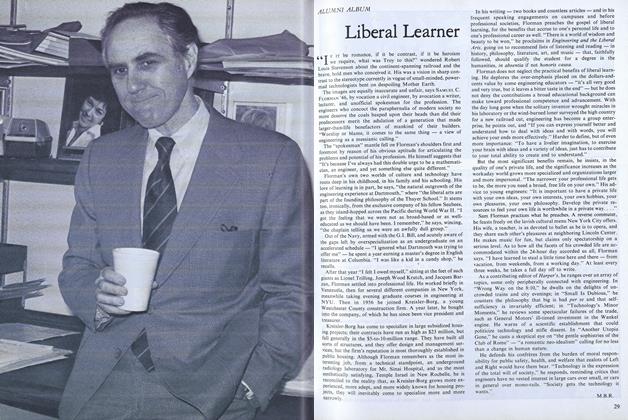

ArticleLiberal Learner

March 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1979 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1979 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHOW THE "IVY LEAGUE" GOT ITS NAME

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureWe Were Soldiers

Mar/Apr 2003 By CASEY NOGA '00 -

Feature

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38 -

Feature

FeatureD C U

May 1956 By GEORGE H. KALBFLEISCH -

Feature

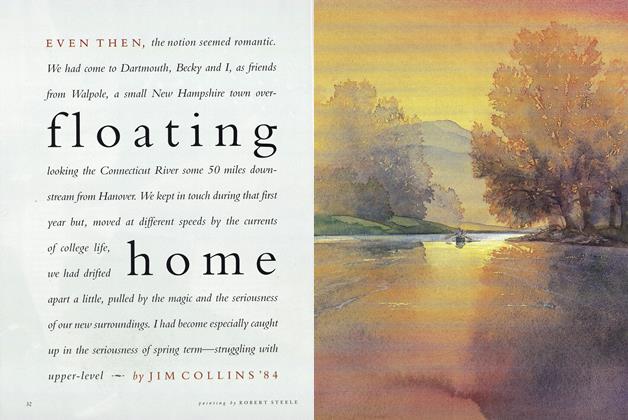

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

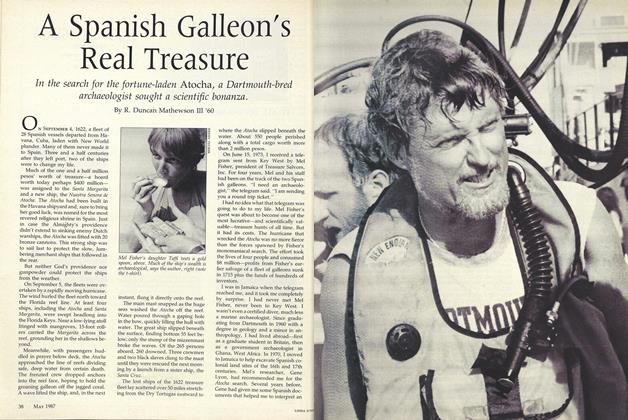

FeatureA Spanish Galleon's Real Treasure

MAY • 1987 By R. Duncan Mathewson III '60