Hostile Takeover

In 1969 the way to rid the campus of ROTC seemed obvious: Occupy Parkhurst Hall.

May/June 2007 MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05In 1969 the way to rid the campus of ROTC seemed obvious: Occupy Parkhurst Hall.

May/June 2007 MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05IN 1969 THE WAY TO RID THE CAMPUS OF ROTC SEEMED OBVIOUS: OCCUPY PARKHURST HALL. IN THIS ORAL HISTORY MANY OF THE PEOPLE INVOLVED RECALL THOSE HIGHLY CHARGED DAYSAND 12 OF DARTMOUTH'S DARKEST HOURS.

By the the spring of 1969 unrest over Americas involvement in the Vietnam War was erupting nationwide. Martin Luther King Jr. had spoken but against the war, calling America "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world" and urging a merger of the civil rights and anti-War movements.

Sentiment against the United States' role in the war was especially strong among college students, whose hometown friends were being shipped to Indochina by the thousands. In 1967 students at the University of Wisconsin demanded that corporate recruiters from Dow Chemical Cos., the manufacturer of napalm, be barred from campus. April 1968 saw a multi-day protest at Columbia University in which members of anti-war and civil rights groups joined forces to protest both the war and Columbia's construction of a new gym. The proposed building was envisioned as an attempt to create a barrier between the university grounds and Harlem, a predominantly black neighborhood. More than 700 students participated in the protest, and about 100 were injured during clashes with authorities.

Dartmouth, too, became politicized. A few anti-war protestors began a weekly vigil by the flagpole on the Green. More students focused their anger about the war on its one local representation—ROTC—and lobbied to ban the program from campus. Students protested in various ways: organizing sit-ins and teach-ins, signing petitions and passing pamphlets. The most daring joined Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a radical antiwar group whose tactics included a threat to incinerate a puppy on the Green to demonstrate the horrors of Dow's despised defoliant.

In January 1969 Dartmouth faculty voted to phase out ROTC over the next four years. To the anti-war activists this wasn't enough. They demanded that ROTC be abolished immediately.

At 3:15 P-m- on May 6,1969, between 75 and 100 people, mostly students, entered Parkhurst Hall to protest the Colleges commitment to a program they felt showed tacit support for the war in Vietnam. They set about ejecting the faculty and staff and barricading themselves in the Colleges main administration building. Not all left their parkhurst offices.

At 8 p.m. the sheriff of Grafton County read an injunction over a bullhorn, stating that anyone who remained in the building after a specified deadline would be arrested. At 3:20 a.m. busloads of state troopers, who had assembled at Lebanon Armory, pulled up outside Parkhurst and broke down its front doors. They carried out 40 undergraduates, two faculty members, two staff members and 12 others as a crowd of about 1,000 watched. Most of those arrested were sentenced to 30 days in jail (where students were allowed to do their coursework) and fined $100.

The ROTC program was gradually phased out, and by 1973 there was no military presence at Dartmouth. ROTC did not return until 1985, when President David T. McLaughlin '54, Tu'ss, overcame faculty sentiment to reinstate the program.

Most of those involved have not remained in touch with each other.

PRELUDE

"I was late, and the meeting inside was short. It was the biggest crowd I ever saw at anti-ROTC meetings, numbering perhaps 250 people. Dave Green was on the stage saying that the time for talking was over; it was time for action. He said he was going over to the administration building; anyone else was welcome. There was no haranguing, no rationalizing. He strode down from the stage and out the door."

STEVEN TOZER

"I arrived at the administration building with a tape recorder shortly after 2:30 p.m. The silence was shattered at 10 past 3 by the footsteps of a panting Jeff McHugh. He had been in College Hall; the vote had been overwhelmingly in favor of occupation—the radicals were on their way."

PAUL GAMBACCINI

"We locked all the files in the deans office. At that time we had files where every one of them had to have a separate lock. I went home with the keys in my shoe."

GINNY CATLIN

"We knew what was going to happen. We didn't lock the door or try to keep them out. John O'Connor, who was the proctor, said to me later, 'lf I'd just had one nun in a black robe standing on the steps saying, you go away, you bad boys! they would have stopped in their tracks.' "

THADDEUS SEYMOUR

"CRACK HIS HEAD WIDE OPEN"

"The demonstrators came in, and I went out and read the riot act twice, went back in my office and then a group started to push me out."

SEYMOUR

"On the main floor Dean Seymour played to one of the least attentive student audiences of his career. As several youths nailed shut the large wooden front door, he strode out of his office and planted himself at the base of the stairs in the marble foyer. 'You are in violation of the regulations of the College Committee on Standing and Conduct,' he bellowed. 'F—-you, a student's voice was heard to reply."

GAMBACCINI

"Paul G. and I were together when President Dickey spoke angrily with any protesters who cared to listen. Because of my long hair he assumed I was a protester and started to chastise me when Paul interceded and said, 'He's with me and WDCR,' which delivered me from the wrath of the president."

JEFFREY MCHUGH

"People used their shoulders and heads to push me down the marble staircase to the basement. Going downstairs, I had gravity on my side, while the students were off balance. I had Greens head under my arm, and as we reached a sharp corner at the bottom of the stair, I realized I could pivot just like that and crack his head wide open. For a fraction of an instant I wanted to do it—but, obviously, I didn't. I reflected on the moment a lot later. It scared me that I could even imagine thinking such a thing.Then David pushed me down the hallway and out the back door, and that was that."

SEYMOUR

THE CAST OF CHARACTERS

(IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE)

STEVEN TOZER '72, a protestor, is a professor in the College of Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. The quotes here are taken from an article he wrote for DAM in 1979.

PAUL GAMBACCINI '70 covered the takeover for College radio station WDCR. A copy of the tape he recorded is available in the archives at Rauner Library. He now lives in London, where he works as a broadcaster for the BBC. Some of the quotes here are taken from his autobiography, Radio Boy.

GINNY CATLIN was a receptionist in the office of the dean of the College.

THADDEUS SEYMOUR served as dean of the College from 1959 to 1969. When the takeover occurred he'd already accepted the presidency of Wabash College in Indiana, where he served for eight years. He was president of Rollins College from 1978 to 1990 and now teaches English there part-time.

JEFFREY MCHUGH '71, covered the SDS meeting—where the anti-war action was voted on for WDCR. He is now an educational consultant and dean of students at Fairfield (Connecticut) Woods Middle School, where he teaches a unit on the 1960s.

ALEXANDER "SANDY" MACKIE III '72, a protestor, was on a fulltuition Navy ROTC scholarship. He resigned his commission and forfeited his scholarship prior to the takeover as a result of the situation in Vietnam. "I came to believe that if I was opposed to the war I couldn't in good conscience remain in the ROTC, he says. He completed a 25-year career as a corporate communications manager with Chevron in 2005.

VLADIMIR SVESKO '69, a protestor, is now a physician specializing in emergency medicine who splits his time between Maui and a Navajo reservation in New Mexico.

DAVID GREEN '71 was the only student protestor to be expelled from Dartmouth for his role in the occupation. After a 15-year career in acupuncture, he now works for Multi-Pure Drinking Water Systems. On a May 2004 business trip to Florida'he visited with Thaddeus Seymour. The two discussed the past and reconciled, both say.

THOMAS GOULET '72, a protestor, is president of an architecturaland woodworking designcompany in Denver, Colorado, andfather of Kaelin '07, who graduates in June.

CHIP ELITZER '69, a bystander, spent two years in the BrazilianAmazon jungle as a Peace Corpsvolunteer after graduating from Dartmouth. He now works as an investment banker in the Berkshires.

ROBERT HEITZMAN '70, a protestor, is currently a consultant with Towers Perrin in New York City and a tournament bridge player.

PAUL MIReNGOFF 71, a protestor, went to Stanford Law School after Dartmouth. He is a lawyer with Akin Gump in Washington, D.C., a blogger at Powerline.com and father of Emily '10.

NEVILLE MODY '69 was the only international student to participate in the occupation. As a result of his participation, his student visa from India was not renewed and he was forced to leave the country within 10 days of his release from jail. He currently works as an environmental activist in India. He never received his Dartmouth degree.

WALTER PETERSON '47 was the governor of New Hampshire at the time of the occupation. From 1975 to 1995 he served as president of Franklin Pierce College. He lives in Peterborough, New Hampshire.

"Each of them [Seymour and Green] represented the others nemesis."

GAMBACGINI

"I was a little alarmed at how quickly things escalated. I had been reading a lot of Henry David Thoreau and Martin Luther King Jr., and I was definitely prepared to participate in a nonviolent protest. I thought it was going to be a much more gentlemanly affair."

SANDY MACKIE

"There were some calm voices but also a lot of screeching voices. There was an element within the group that was determined to have a high-profile confrontation."

VLADIMIR SVESKU

NOW WHAT DO WE DO?

"I was out of the building by 4; we went to Jack Stebbins's law office and started the injunction process. There were five or six of us from Dartmouth, including President Dickey. Also present were Jack, several other lawyers, the governor and members of his staff. We spent a lot of time around the conference table trying to figure out what to do."

SEYMOUR

"Nearly all the employees were out, with the exception of a faculty member in a basement office who was said to have heart trouble. Word spread that he was to be left alone; there seemed to be an unspoken agreement that our action should cause no injury. To my knowledge, it caused none. At this time people began milling throughout the building, taking stock of the situation and talking over strategy. It was certainly not clear what we would accomplish by occupying the building."

TOZER

"After we got everybody out, we looked at each other and said, 'Now what do we do?' Somebody took out a guitar and we started playing Beatles songs. We watched through the windows as a huge crowd started gathering on the front lawn."

DAVID GREEN

TWO SIDES

"The street was blocked with the curious, the sympathetic and the vociferously hostile. I recall my extreme puzzlement that these students could be so upset over the temporary occupation of property and yet remain calm in the face of hundreds of thousands of dead and mutilated bodies less than a day's jet-ride away. I was shaken by what seemed an impossibly wide gulf between that group and those in the building."

TOZER

"There was a real divide between the tweeds and the pipes and the bell bottoms and the tie-dye shirts."

THOMAS GOULET

"I found that the protesters tended to be strident and quick to put people in any position of authority on the other side and to treat people who differed from their point of view as less worthy of civility. Slogans were taking over for thought; simply by stating or chanting something loudly or repetitively enough, that trumped any rational discussion."

CHIP ELITZER

POINT OF NO RETURN

"Various ideas were now considered, and some decided to stay until forcibly ejected. It would, even if the ROTC issue was lost, demonstrate that this issue was not just a student whim; it was a principle that we were willing to risk our college careers to defend."

TOZER

"I left the building after being advised that if I remained after the injunction was served, I'd be a candidate for the clink."

GAMBACCIN

"When the New Hampshire troopers arrived, the crowd outside was incredibly agitated. People were cheering them; people were screaming at them. The police used a battering ram and eventually broke the doors down. We were on the steps right inside the big doors. We had linked arms and we were chanting: 'U.S. out of Vietnam, ROTC out of Dartmouth.' That was a very electric moment."

GREEN

WHY IT HAPPENED

"For me and many of the others of that time, political conviction did not arrive suddenly; it had been growing quietly For years. Mario Savio and the Berkeley free-speech movement had come into our Midwest home in Life magazine; Martin Luther King had marched and blacks had been beaten on home television; and Bob Dylan sang Masters of War' and 'The Times They Are a Changin on the radio. And they all spoke of ideals that home and school had taught me to respect: freedom, justice and equality among people."

TOZER

"We were a generation that was traumatized by assassinations, the horrible brutality of the Vietnam War and the violence associated with the civil rights movement. We had lost faith in the effectiveness of legitimate civil channels."

GREEN

"The young people in 1969 had a very defined sense of themselves as a separate generation. They had been through the civil rights movement on the side of Martin Luther King and that had trained them for a mindset of opposition to established authority. Vietnam tipped them over the side."

CAMBACCINI

"The whole point was to get in the way. Wherever they drew the line, we were going to cross it."

ROBERT HEITZMAN

"We were not interested in fitting into the society, we were interested in fitting out of it. It wasn't just the war. At that point in the 1960s a lot of people were looking to change the way they were living. A certain cultural revolution was going on that swept a lot of people along with it."

SVESKO

"I'd like to tell you that I did it purely out of political conviction, but some of it definitely had to do with being swept up in the emotions of the times."

MACKIE

"Being a radical held more panache back then."

PAUL MIRENGOFF

"Idealism was still alive."

NEVILLE MODY

LOOKING BACK

"I spent two terms as governor. Parkhurst was the most meaningful single thing because of my emotional ties to Dartmouth and because it was my first big challenge."

WALTER PETERSON

"I had a lot to do with writing Dartmouth's regulations on freedom of expression and dissent as well as its terms of''orderly process.' Now, as an English professor, I teach my students 'Letter from Birmingham Jail,' in which Martin Luther King Jr. writes that the biggest obstacle is the white moderate who says, 'I believe in What you're fighting for. I just think that you should take more time and be more orderly.' He describes them as people who care more about order than justice. And I was caught between those two poles. I think we all were."

SEYMOUR

"In retrospect, there was a lot of antagonism created that did not need to be created."

SVESKO

"What was interesting to me was that as soon as [President] Nixon abolished the draft, this moral fervor evaporated. If you listened to the anti-war protesters, they got on their moral high horse and expressed in general principles that the war was wrong. If that was true, why did removing their exposure to the war cause that cacophony of protest to fall silent?"

ELITZER

"I wish I had not participated. I don't think that we were on the right side."

MIRENGOFF

"The mechanisms by which the United States understands the world are very limited. The entire episode hung around the issues of free speech and the limits of power."

MODY

"To tell you the truth, I feel no bitterness about being expelled. I felt like I did what I had to do, and Dartmouth did what it had to do. Both of us were true to our principles. It was like I'd ordered a meal and then the meal wag served. As I reflect back, there are things I wish we'd done differently. We were extremely self-righteous. We hadn't learned to listen. I think ultimately we were on the side of morality, but we didn't think through all the emotions we were stirring up and the polarization. We were very full of ourselves."

GREEN

"Even though I went on to be a respectable member of corporate society, I am still proud of what I did."

MACKIE

"I have never regretted the episode that was Parkhurst '69. Part of who I am now is whatever small courage or abandon it took to join my fellows against Dartmouth's military cooperation."

TOZER

As protesters addressed the crowd in front of Parkhurst from the front door and upstairs windows, curious students gathered on the lawn.

Students gathered inside as tensions mount; Dean Seymour tried to reason with protesters before leaving the building; buses took prisoners away as onlookers jeered and cheered.

MARY SEYMOUR, the daughter of Thaddeus Seymour, is a writer/editorwho works at Northfield Mount Herman School in Gill, Massachusetts.Andrew Mulligan '05, a former DAM intern, lives and writes in Brooklyn,New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

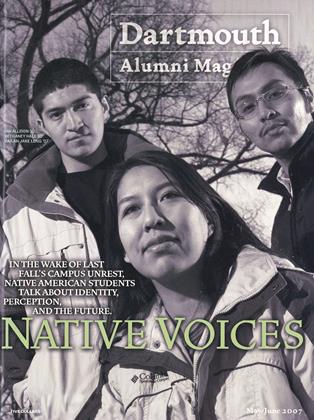

Cover StoryNative Voices

May | June 2007 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’05 -

Feature

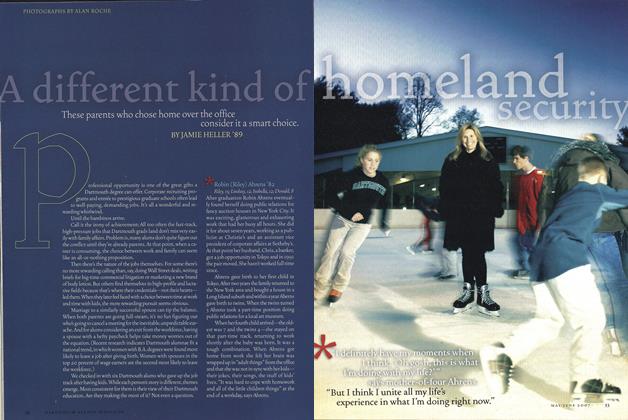

FeatureA Different Kind of Homeland Security

May | June 2007 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2007 By Joe Novak '52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May | June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2007 By BONNIE BARBER

Features

-

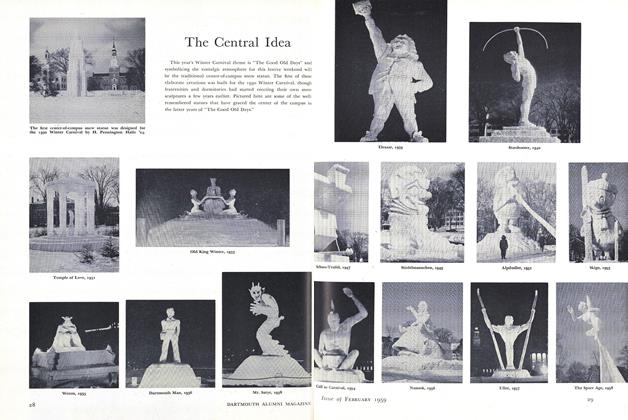

Feature

FeatureThe Central Idea

FEBRUARY 1959 -

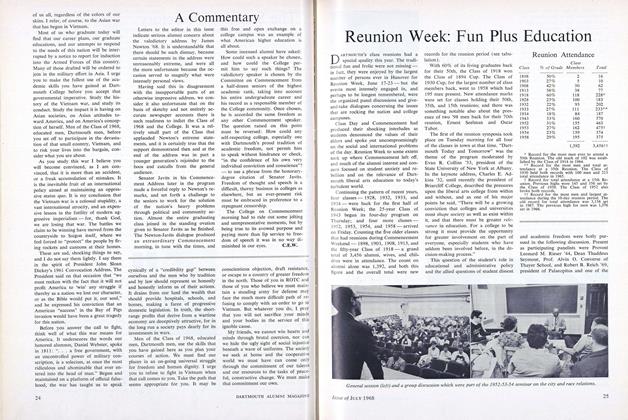

Feature

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

JULY 1968 -

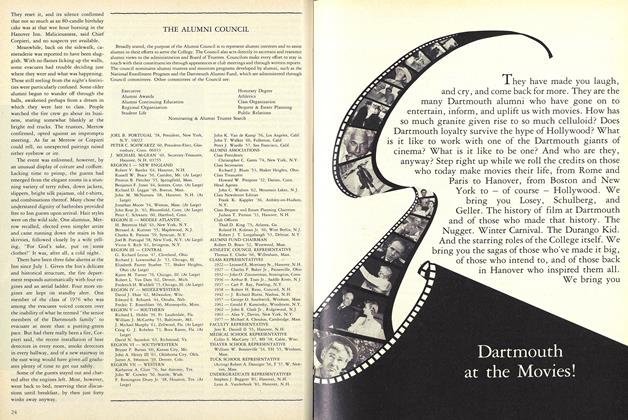

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth at the Movies!

November 1982 -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Cover Story

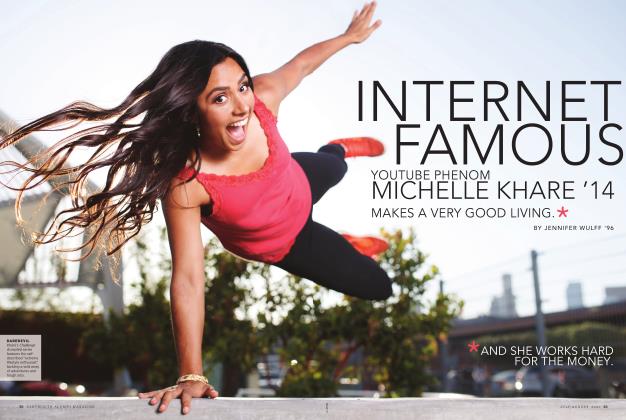

Cover StoryInternet Famous

JULY | AUGUST 2020 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN