EARLY in the 20th century, the scholars of Korea enjoyed a position second only to that of the emperor, and after the scholars came the farmer-landowners. At that time there lived, in the northern part of the country, near the Yalu River separating Korea and Manchuria, a landowning family named Chung.

The Chungs had lived in the village of Pyung Book for generations, 21 generations, in fact, ever since an ancestor from the south had been exiled there in the 15th century for choosing the wrong side in a royal shoot-out. The family was prosperous, father Chung having several businesses as well as the land, but his children suffered under the thumb of an unkind stepmother. In 1934, one of them, 16-year- old Sung Kook, ran away from home to Tokyo. There, for a while, he went to night school, but he was also learning to drive, and when he began earning money as a taxi-driver, he lost interest in the schooling.

Half a century later, Sung Kook Chung sat in a comfortable white house on Fairview Avenue in Hanover, recalling his'wild youth: "I was a pretty nutty boy, you know. Crazy, reckless. Now I know that education was the key, but when money starts coming through, who wants to go to school?" He laughed knowingly.

Young Chung returned to his father's home in 1940, and there his parents arranged his marriage to Kim Ye Rock. Then came 1945 and the partitioning of Korea. "After the Communists occupied North Korea," Sung Kook recalled, "they started changing everything around. They transferred the rich people away from their home towns, and we lost everything." In 1947, feeling he could take it no longer, Sung Kook made plans to get out. "Where will you go?" asked his horrified family. "Down south," replied the fearless traveler. And so, on foot, young Chung made the dangerous trek across the 38th Parallel into South Korea, where he knew no one. After six months of hand-to-mouth existence in Seoul, he found a job driving a jeep for the American Army. Then, again on foot, he braved the political dragons a second time, to bring his wife out of North Korea.

Chung paused in his recounting and leaned forward. "You just do it, you know? Thinking this, thinking that, you'll never make it. Sometimes I wonder about American families. It has never happened here, but if the country were invaded, what would they do? Carry the TV? Want this, want that? Just get out, that's all."

When South Korea became a republic in 1948, Chung's army unit became the American embassy, and Chung automatically became an embassy chauffeur. Buffeted about as the Cold War developed, the embassy was driven out of Seoul in 1950, only to return later the same year, only to leave again when U.N. forces abandoned and evacuated the city. The embassy then moved to Pusan, a refugee setting of chaos and great poverty.

The new American ambassador to Korea, Ellis O. Briggs '21, arrived in Pusan with his wife Lucy in the fall of 1952. Chauffeur Chung was the first Korean they met, and it did not take them long to discover how remarkable he was and to become his friends. Shortly after the embassy returned to Seoul in 1953, the Briggses were reassigned, to Peru. Chung told Lucy Briggs he wanted to go to the United States when they left Korea. She tried to talk him out of it, she said, feeling that the difference between the two cultures would be devastating. But Chung was heart-set on securing an education for the three children who had been born to him and Kim Ye Rock, an education he could not afford in Korea.

The question was how to get the Chungs out. A friend of the Briggses, Col. John Ames '16, suggested they contact Dartmouth College for help. The ambassador sat down at once and wrote to his friend Sidney Hayward '26, then secretary of the College, recommending Chung. Hayward and his wife Barbara agreed to sponsor the Korean family and promised to see to the necessary job offer and housing. Lucy Briggs relayed the news to Chung and asked him how his wife would feel about it. "I asked her if she wanted to go to the United States," said Chung. "She said, 'Will it be hard? As hard as Pusan?' 'Yes,' I told her, 'it will be as hard as Pusan but no harder.' 'Very well, then', she said. 'I will go.' "

The intrepid couple left their homeland forever in September of 1955, taking one bag's worth of possessions and their children, Kyung Hi, 6, Won Kun, 3, and Won Hyung, 9 months the first Koreans to come to the United States under the U.S. Refugee Relief Act of 1953. Dartmouth had arranged a job for Chung as a carpenter in Buildings and Grounds, and vigorous housing efforts by the Hanover Women's Club had secured a two-bedroom apartment and furnished it.

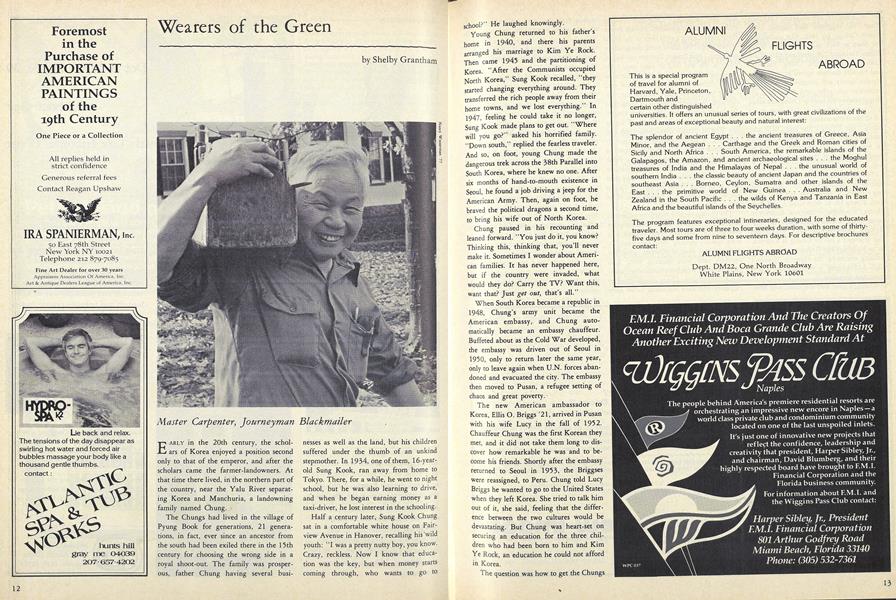

Chung, a good auto mechanic, was, however, no carpenter. Long-time College mason and union president Stewart Fraser remembers Chung's early days in the Dartmouth shop. "He knew some things about carpentry," said Fraser, "but not our way of doing it. He was used to hand tools." He mentioned Chung's popularity in the shop and described how quickly and how well Chung learned the trade, despite the considerable language problem. Chung also developed a shop specialty door-closers. "He has developed a technique of taking any kind of outside door-closer apart and repairing it so it operates and operates well," said Fraser. "He's really an expert at the door-closing business. I don't think there's another man here who could do what he did the other day to that huge glass door at Hopkins Center in the time that he did it. Yes, Chung's a person who, if he does a thing, does it well."

The Chungs became American citizens as soon as they could, to secure citizenship for their children, and then began to work with them toward securing their educations no mean task even in America, given the numbers they were working with. Two more children were born in Hanover, making a total of five. Chung moonlighted at carpentry and auto mechanics to set aside money for land, and in 1959, the couple bought the lot on Fairview and Chung built their home on it, a simple, pleasant white clapboard house that he and Kim Ye Rock now occupy alone, for the children have all flown the nest on the wings of substantial Ivy League scholarships.

Kyung Hi, Chung's daughter, went to Smith as an undergraduate and then to Dartmouth and the University of Pennsylvania medical schools. She now lives in Farmington, Connecticut, and practices internal medicine at Hartford Hospital. Won Kun '73, first of the four sons, ran out of courses to take at Hanover High when he was a sophomore there and began taking Dartmouth courses in his junior year, at the end of which he enrolled at Dartmouth as a sophomore. Graduate scholarships took him to Yale and to Switzerland, and he now has his own graphic design firm in Brookline, Massachusetts. Harvard graduate Won Hyung went to Stanford University Business School for his M.B.A. and now works in New York City with Morgan Stanley Investments. James and Robert have followed Won Hyung to Harvard, where the older, now a senior, is majoring in mechanical engineering, and the younger, a sophomore, is mulling over the possibilities of a career in economics. Like the man said, whatever Chung does, he does well.

The Chung children spoke gratefully of having been pushed through the educational blind spots of childhood - those times when the homework palled and the television called and they were quick to give credit also to Hanover's schools and to the American scholarship system. Chung's own description of his ruling passion brought out his sense of humor, which is, as Kyung Hi said, "on the dry side." "I am a blackmailer," he said, grinning.

"I scared them. Each child was badly spanked one time, every one one time, that's all, just once. I used a small stick and really spanked. It was like horse-breaking: one time you did that and after, when there was trouble, you just reminded them. I never needed to spank them again. The bad times came about the 11th grade, when they started to have their own ideas. We begged them that until after high school, as long as they were under our roof, they would go by my way. Then, we said, you are free. So, whether they liked it or didn't like it, they had to wait. That was our agreement." Chung smiled. "One-sided agreement, right? Dictatorship."

Then he leaned forward and said very seriously, "But you think about it. American people love children. The little children play with knives. They take the knives away, right? Danger, right? What is the difference when the big boys play some other way? If there is danger you have to stop it. But, you say, we don't want to bother their freedom. Let them go, smoke dope, go this way, go that. But if you really love them, you've got to stop that."

Chung has been back to Korea once, for a week only, to pay his respects to his father's tomb. Kim Ye Rock has never been back. America is their country, say all the children, and they feel no particular tug to visit Korea. Sung Kook Chung, after 25 years at Dartmouth, is beginning to think about retirement. He will probably continue his hobby of fine cabinetwork, several handsome black-and-mother-of-pearl examples of which adorn his home. "Right now, I'm building three oak chests of drawers," he said. "Busy, busy, you know. One child asked me to make one, and when it was done, the next child looked like he would like to have one, too. So I make another, and another. It costs money, but they will say, This was made by my dad.' That makes it nicer, doesn't it?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Now we had to go in different directions"

November 1981 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureA record of their fame

November 1981 By Eddie O'Brien -

Feature

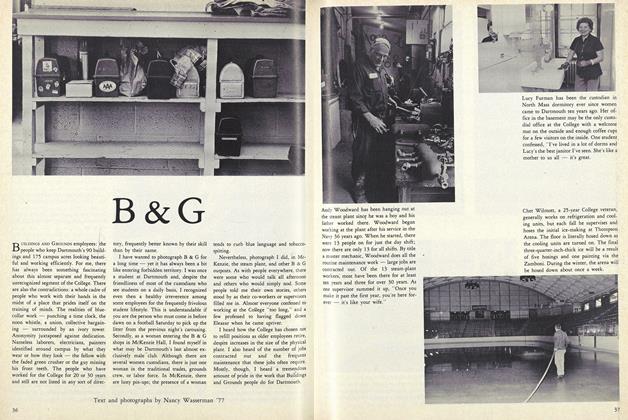

FeatureB & G

November 1981 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1981 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

November 1981 By Robert H. Conn -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

November 1981 By Robert D. Blake

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

MARCH 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

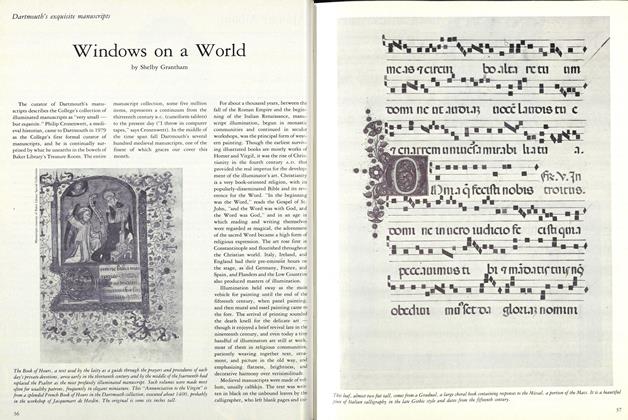

FeatureWindows on a World

DECEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham

Article

-

Article

ArticleWHO'S WHO ON THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

January, 1926 -

Article

ArticleMedal for Ray Comerford

DECEMBER 1931 -

Article

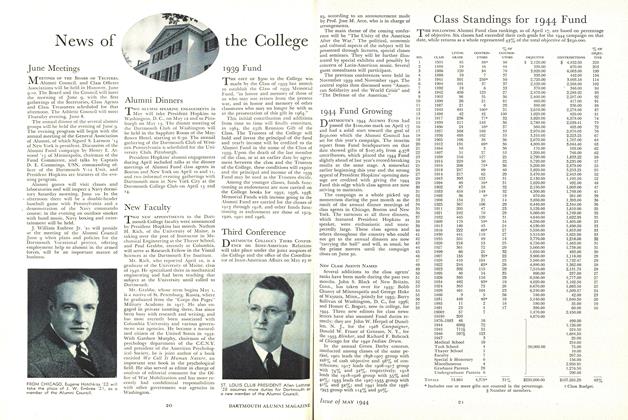

ArticleClass Standings for 1944 Fund

May 1944 -

Article

ArticlePresident Changes Staff

NOVEMBER 1971 -

Article

ArticlePresident of the Year

June 1975 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR LORD'S HISTORY OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, 1815-1909*

March, 1914 By Herbert Darling Foster