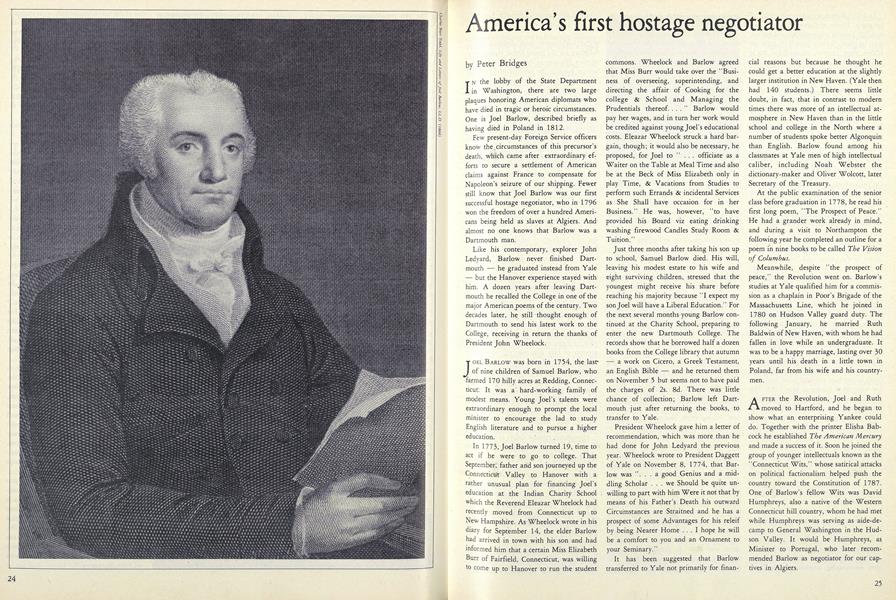

IN the lobby of the State Department in Washington, there are two large plaques honoring American diplomats who have died in tragic or heroic circumstances. One is Joel Barlow, described briefly as having died in Poland in 1812.

Few present-day Foreign Service officers know the.circumstances of this precursor's death, which came after extraordinary efforts to secure a settlement of American claims against France to compensate for Napoleon's seizure of our shipping. Fewer still know that Joel Barlow was our first successful hostage negotiator, who in 1796 won the freedom of over a hundred Americans being held as slaves at Algiers. And almost no one knows that Barlow was a Dartmouth man.

Like his contemporary, explorer John Ledyard, Barlow never finished Dartmouth he graduated instead from Yale but the Hanover experience stayed with him. A dozen years after leaving Dartmouth he recalled the College in one of the major American poems of the century. Two decades later, he still thought enough of Dartmouth to send his latest work to the College, receiving in return the thanks of President John Wheelock.

JOEL BARLOW was born in 1754, the last' of nine children of Samuel Barlow, who farmed 170 hilly acres at Redding, Connecticut': It was a' hard-working family of modest means. Young Joel's talents were extraordinary enough to prompt the local minister to encourage the lad to study English literature and to pursue a higher education.

In 1773, Joel Barlow turned 19, time to act if he were to go to college. That September, father and son journeyed up the Connecticut Valley to Hanover with a rather unusual plan for financing Joel's education at the Indian Charity School which the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock had recently moved from Connecticut up to New Hampshire. As Wheelock wrote in his diary for September 14, the elder Barlow had arrived in town with his son and had informed him that a certain Miss Elizabeth Burr of Fairfield, Connecticut, was willing to come up to Hanover to run the student commons. Wheelock and Barlow agreed that Miss Burr would take over the "Business of overseeing, superintending, and directing the affair of Cooking for the college & School and Managing the Prudentials thereof. ..." Barlow would pay her wages, and in turn her work would be credited against young Joel's educational costs. Eleazar Wheelock struck a hard bargain, though; it would also be necessary, he proposed, for Joel to ... officiate as a Waiter on the Table at Meal Time and also be at the Beck of Miss Elizabeth only in play Time, & Vacations from Studies to perform such Errands & incidental Services as She Shall have occasion for in her Business." He was, however, "to have provided his Board viz eating drinking washing firewood Candles Study Room & Tuition."

Just three months after taking his son up to school, Samuel Barlow died. His will, leaving his modest estate to his wife and eight surviving children, stressed that the youngest might receive his share before reaching his majority because "I expect my son Joel will have a Liberal Education." For the next several months young Barlow continued at the Charity School, preparing to enter the new Dartmouth College. The records show that he borrowed half a dozen books from the College library that autumn a work on Cicero, a Greek Testament, an English Bible and he returned them on November 5 but seems not to have paid the charges of 2s. 8d. There was little chance of collection; Barlow left Dartmouth just after returning the books, to transfer to Yale.

President Wheelock gave him a letter of recommendation, which was more than he had done for John Ledyard the previous year. Wheelock wrote to President Daggett of Yale on November 8, 1774, that Barlow was "... a good Genius and a mid dling Scholar . . . we. Should be quite unwilling to part with him Were it not that by means of his Father's Death his outward Circumstances are Straitned and he has a prospect of some Advantages for his releif by being Nearer Home ... I hope he will be a comfort to you and an Ornament to your Seminary."

It has been suggested that Barlow transferred to Yale not primarily for financial reasons but because he thought he could get a better education at the slightly larger institution in New Haven. (Yale then had 140 students.) There seems little doubt, in fact, that in contrast to modern times there was more of an intellectual atmosphere in New Haven than in the little school and college in the North where a number of students spoke better Algonquin than English. Barlow found among his classmates at Yale men of high intellectual caliber, including Noah Webster the dictionary-maker and Oliver Wolcott, later Secretary of the Treasury.

At the public examination of the senior class before graduation in 1778, he read his first long poem, "The Prospect of Peace." He had a grander work already in mind, and during a visit to Northampton the following year he completed an outline for a poem in nine books to be called The Visionof Columbus.

Meanwhile, despite "the prospect of peace," the Revolution went on. Barlow's studies at Yale qualified him for a commission as a chaplain in Poor's Brigade of the Massachusetts Line, which he joined in 1780 on Hudson Valley guard duty. The following January, he married Ruth Baldwin of New Haven, with whom he had fallen in love while an undergraduate. It was to be a happy marriage, lasting over 30 years until his death in a little town in Poland, far from his wife and his countrymen.

AFTER the Revolution, Joel and Ruth moved to Hartford, and he began to show what an enterprising Yankee could do. Together with the printer Elisha Babcock he established The American Mercury and made a success of it. Soon he joined the group of younger intellectuals known as the "Connecticut Wits," whose satirical attacks on political factionalism helped push the country toward the Constitution of 1787. One of Barlow's fellow Wits was David Humphreys, also a native of the Western Connecticut hill country, whom he had met while Humphreys was serving as aide-decamp to General Washington in the Hudson Valley. It would be Humphreys, as Minister to Portugal, who later recommended Barlow as negotiator for our captives in Algiers.

In 1787, Barlow arranged publication of his poem, Vision of Columbus, which ran to 5,000 lines. It was pompous, and not entirely original, leaning heavily in style on Milton, Pope, Juvenal, and the Bible. But it proved popular, ran through several printings, and appeared in both England and France. The basic idea was simple: A "radiant Seraph" appears to Columbus, moribund in prison, and takes him up to the Mount of Vision to look at the powerful America that will spring from his discovery. The mention of Dartmouth comes as the seraph points out America's colleges:

Great without pomp the modest mansions rise;

Harvard and Yale and Princeton greet the skies; Penn's ample walls o'er Del'ware's margin bend, On James's bank the royal spires ascend, Thy turrets, York, Columbia's walks command, Bosom'd in groves, see growing Dartmouth stand;

While, o'er the realm reflecting solar fires, On yon tall hill Rhode-Island's seat aspires.

By the end of 1787, Barlow was an established writer; he had also been admitted to the Connecticut bar. But he was restless, and not very well off, and eventually he went to Europe as the agent of a shaky if not shady land-development scheme. The Scioto Company had been authorized by Congress, and "the principal characters in America" were claimed among its shareholders. The idea was to purchase several million acres of Ohio land at a dollar an acre and resell it in Eufope to business speculators or would-be immigrants at a considerably higher price. The Company had still not raised sufficient funds to purchase the land when Joel Barlow went off to Europe in May 1788. The entrepreneurs hoped to obtain from European bankers a bridging loan which would enable the company to pay for the land and which could then easily be repaid from the land sales to Europeans. Unfortunately the scheme did not work, and when the first French settlers arrived in America early in 1790 they found they could not get title to "their" land. Barlow seems to have acted in good faith as the company's agent, however, and he continued to enjoy a good reputation among the many leading inhabitants of London and Paris with whom he had become acquainted, a distinguished body that included the Marquis de Lafayette, Thomas Jefferson, then U.S. Minister to France, and Sir Joseph Banks of the Royal Society, all of whom had recently been encouraging another notable Dart mouth drop-out, John Ledyard, in his travels.

After Barlow's business mission failed he turned to a life as political writer in Europe. There was revolution in France and ferment in England, and Barlow welcomed the turmoil and wanted to be a part of it. By 1790, he had become an active member of the London Society for Constitutional Information, one of several English groups lending sympathy and support to the French Republicans and hoping for reform in England. For the moment, English politics stood in the condition that Winston Churchill was to label "peaceful triteness." Louis XVI was still living; Bonaparte was still a subaltern; England and France were at peace; and Prime Minister Pitt prophesied many more years of peace. Meanwhile, Barlow was writing, helping to destroy the peaceful triteness: first a caustic poem on "The Conspiracy of Kings" and then, in 1791, a volume of political essays called Advice to the Privileged Orders, a fierce attack on abuses in European government.

After a long visit to France in 1792, Barlow wrote a 70-page Letter to the French National Assembly. It was a treatise on good government, and it expressed a good American point of view on such matters as equality of rights, the people's ability to govern themselves, the danger of a national church, and the need to grant independence to colonies. The Assembly showed its appreciation by granting French citizenship to Joel Barlow, the third American after Washington and Hamilton to be so honored. But events in France had now turned violent, and in England, government took an anti-radical turn. Tom Paine, whose Rights of Man had just appeared, was charged with seditious libel, and Barlow, fearing arrest, fled to France.

The succeeding years were not unkind to Barlow, despite the terror and turmoil of the revolution. Although he had not stopped being an American, he decided to make use of his new French citizenship and seek election to the National Assembly as a deputy from Savoy.

But Barlow failed of election, which may have saved his head, since many deputies lost theirs in the Terror. Barlow was not even arrested in France, although his friend Tom Paine was. To the contrary, he now began to make money, first as a shipping agent and later in French government securities, which he bought cheap and which rose steeply in value after Napoleon began to win battles. Eventually, Joel Barlow was a wealthy man.

BARLOW'S career as a diplomat began when his old friend David Humphreys, by then Minister to Portugal, came to see him in Paris in the summer of 1795 and offered him the job of securing the release of over a hundred American sea-captains and sailors held captive by the Dey of Algiers. The Barbary pirates had first caused trouble for the new American republic in 1785, when a Boston schooner was captured off Portugal and taken to Algiers, and in the next few years a number of American vessels were taken. It should have been clear that a strong navy would be necessary to stop this piracy. President Washington had in fact emphasized the need for a navy in his 1793 message to Congress, but national sentiment remained divided. Some thought a navy would put too much power in the hands of the federal government, and no one was anxious to pay the taxes necessary to build and maintain a fleet. So the Americans negotiated and paid tribute and ransom which, it has been suggested, cost as much as the navy would have. Minister Humphreys comprehended this situation fully, but as diplomat-on-thespot of a country without a fleet, he could only negotiate.

Barlow accepted Humphreys' offer to become U.S. representative at Algiers. He installed his wife in a comfortable apartment in Paris, spent several months buying presents to help win over the notables of Algiers, and left Paris southbound in January 1796. Meanwhile the Dey of Algiers and another American emissary, Joseph Donaldson, had reached an agreement calling for release of the American captives in return for payment to the Dey of over a half-million dollars, plus annual tribute.

Humphreys foresaw delays in raising the funds and believed that, despite conclusion of the treaty, Barlow's presence in Algiers would be valuable. Barlow reached his destination in March and found Donaldson still there. The two seem to have gotten on reasonably well, but Donaldson left for Italy after a month, leaving Barlow in sole charge of protecting American interests above all, seeing to actual release of the prisoners.

As the spring of 1796 turned into hot summer, there was no sign of the gold needed to redeem the captives. Congress and the President had approved the agreement there was no doubt of American willingness to pay up but there was the question of finding the bullion in a warring Europe where gold was in short supply. Payment was finally arranged through a banker at Algiers named Micaiah (the Americans called him Joseph) Baccri, a native of Leghorn. It was a complex deal, possibly masterminded from the start by Barlow, that involved transferring a laundered loan worth some $200,000 from the Dey to local French authorities and thence into the control of Baccri. This done, Barlow asked Baccri to accept liability for the whole half-million-dollar treaty debt owed by Washington to the Dey, against a U.S. credit of $400,000 payable to the Baccri house at Leghorn plus some promises. And this was done. It may have turned out to be good business for Baccri, but it was also, in the words of one historian, "a remarkable gesture of faith in the new United States of America and in the person of that nation's representative at Algiers."

Finally, the Dey was willing to let the Americans go. Plague had broken out meanwhile, and several of the captives had died. Barlow chartered the only ship available from Baccri, the banker named a captured captain as master, and on July 12, 1796, watched as the Fortune sailed out of Algiers harbor with 137 American "former hostages." Barlow had to remain in Algiers because, despite Baccri's agreement to be liable for the debt, the money had not been paid. And there were treaties still to be completed with both Tunis and Tripoli. As Barlow wrote sadly to his wife, "I am the only American slave in Algiers." Most of the required gold arrived in October, but the treaties took longer and it was not until July of 1797, a full year after release of the captives, that Barlow left Algiers, obviously pleased with his accomplishments. The treaties meant tribute, but for the first time in years the prisons of Algiers were free of Americans.

Barlow found his wife in good health in Paris. They settled down for several years in Napoleon's France and then finally came home to America in 1805, 18 years after he had left. They decided to settle in the District of Columbia, where Barlow had good friends, including President Jefferson, and where he wanted to help found a national institution that would combine the functions of an academy of sciences, a great museum, and a national university a dream partly realized after his death in the Smithsonian Institution. In 1807, the Barlows bought a mansion on 30 acres just across Rock Creek from Georgetown, which they named Kalorama, or "fine view" in Greek. Here Barlow wrote his longest work, The Columbiad, a poem of 450 pages which was an expanded version of his earlier Vision of Columbus. President John Wheelock of Dartmouth wrote a complimentary letter, acknowledging receipt of a copy for the College library. President Jefferson was also complimentary but said that he would wait for his retirement to read it through. It was, in fact, dull and over-long.

AFTER four relatively quiet years at Kalorama, his country called once more on Joel Barlow. He was 57 years of age and commencing work on a history of the United States, a project suggested by Thomas Jefferson, when he was recruited for a mission for which his experience particularly fitted him.

The reciprocal blockades declared by Britain and France had made havoc of American shipping and commerce with Europe. Joel Barlow a good friend, an honorary citizen, and long-time resident of France was deemed the best possible negotiator of U.S. claims for ships and property impounded by the French. President Madison appointed him minister plenipotentiary and put the frigate Constitution at his disposal. Accompanied by his wife and his favorite nephew Thomas Barlow to act as secretary, he set sail from Annapolis in August of 1811.

In his message to Congress that November, the President called for in creased military preparedness, since British actions "... have the character, as well as the effect, of war on our lawful commerce." He expressed hope of a settlement with France, however: "... our minister plenipotentiary, lately sent to Paris, has carried with him the necessary instructions. ..."

The Barlows' arrival in Paris was followed by a long wait and a lot of inconclusive talk. The Emperor's attention was fixed on the impending invasion of Russia, which he began in June 1812, and Minister Barlow must have wondered if there were any chance of the French considering the American claims. Finally, though, in October the French foreign minister, Bassano, wrote to Barlow from Vilna, in Lithuania, that "... if you will come to this town ... we will immediately be enabled to remove all the difficulties which until now have appeared to impede the progress of the negotiation."

Barlow, nothing daunted, left Paris for Vilna on October 25 in his carriage, leaving Ruth but taking his nephew along. Traveling at times all night, they finally reached their destination on November 18, after three weeks and 1,100 miles. The weather had been mild and their spirits high; Barlow wrote from Koenigsberg that "my patriotism created a great anxiety to get on fast, and that anxiety gave out a constant supply of animal spirits. ... " But bitter winter weather arrived with them at Vilna and so did the news that Napoleon was in full retreat from Russia, headed their way. Soon afterward came reports that Napoleon had left his army behind and was riding hell-bent for Paris.

There was no reason now for Barlow and his nephew to linger in Lithuania. On December 5, they left Vilna, intending to take a southern route Krakow/Vienna/Munich to Paris. The temperature fell to 12 to 14 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, and the cold in his unheated carriage, along with his sense of disappointment, began to work its effect on Joel Barlow. By the time the party reached Zarnowiec, a little town north of Krakow, Barlow had pneumonia. Several days later, just at Christmas, he died. He lies still in Poland.

With classical allegory, The Columbiad heralded American achievements and hopes.

Peter Bridges '53, a career diplomat, iscurrently deputy chief of mission at the U.S.Embassy in Rome. His chronicle of JohnLedyard, "A Triumphant Failure,"appeared in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE inOctober 1980.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

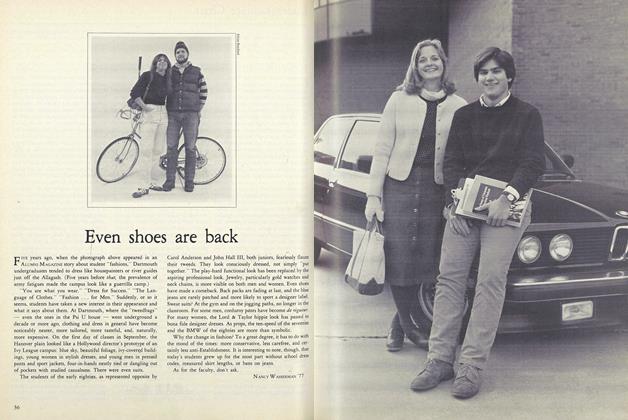

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

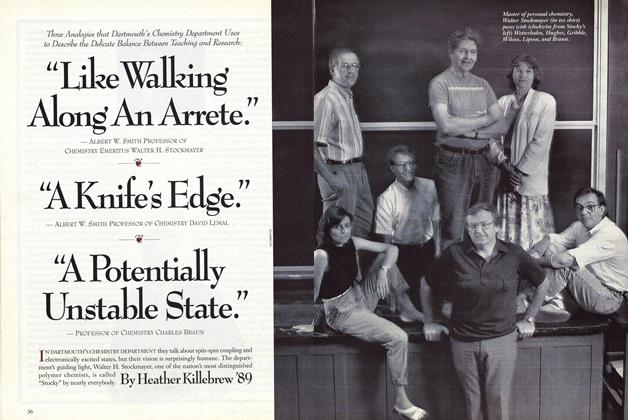

Class Notes1932

December 1981 By Adrian A. Walser

Features

-

Feature

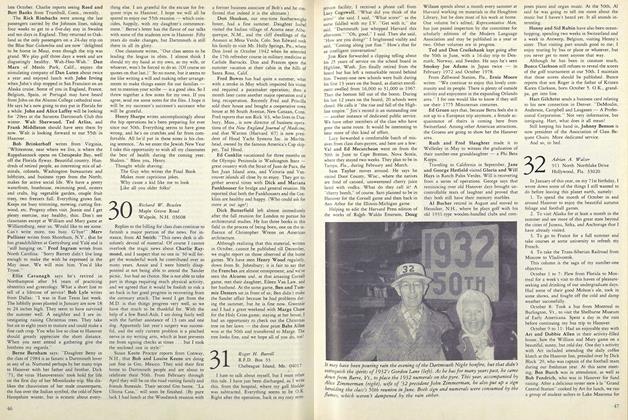

FeaturePsychologists Discuss World Tensions in a Conference Dedicating Gerry Hall

June 1962 -

Feature

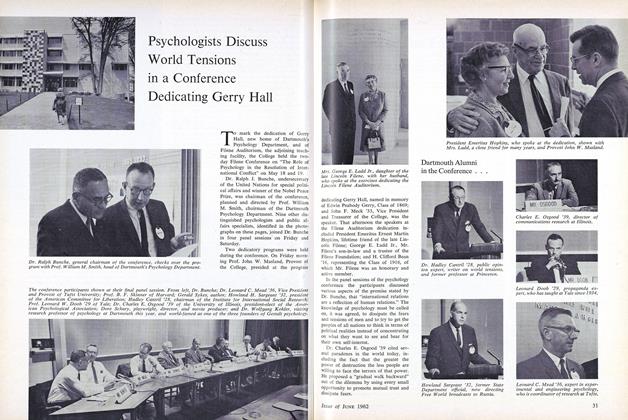

FeatureDARTMOUTH IN THE PEACE CORPS

MAY 1963 By Clifford L. Jordan Jr. '45 -

Feature

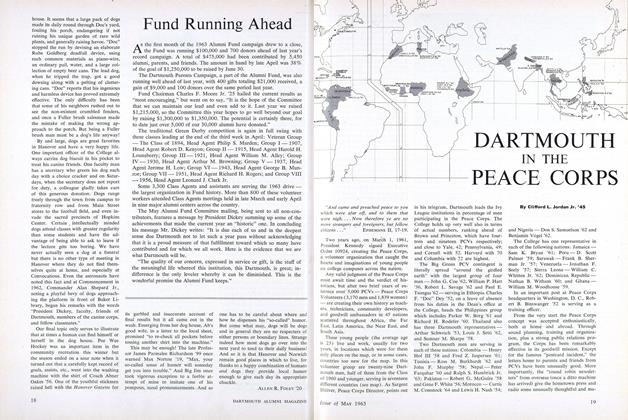

Feature"Like Walking Along an Arrete."

OCTOBER 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Cover Story

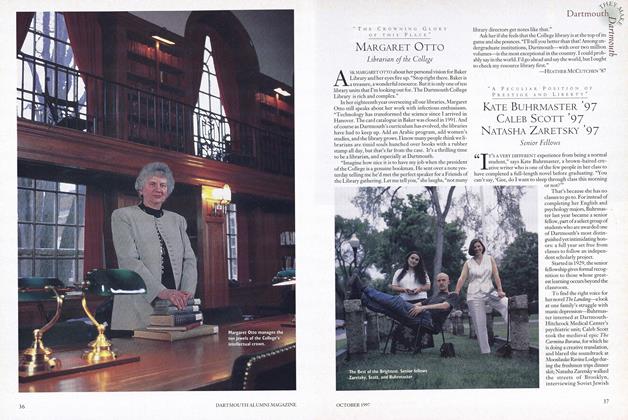

Cover StoryMargaret Otto

OCTOBER 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLouis Burkot

OCTOBER 1997 By Jon Douglas '92 -

Cover Story

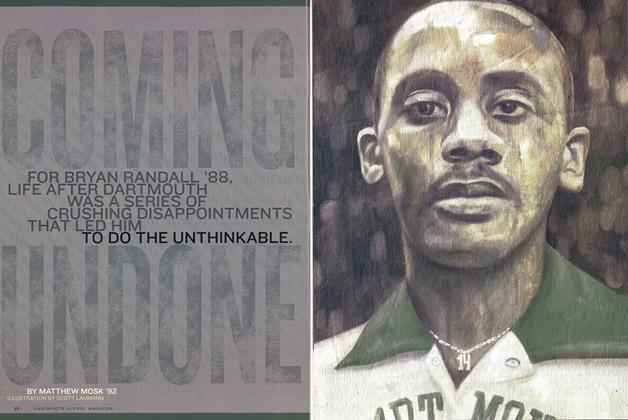

Cover StoryComing Undone

Jan/Feb 2005 By Matthew Mosk ’92