David McLaughlin's

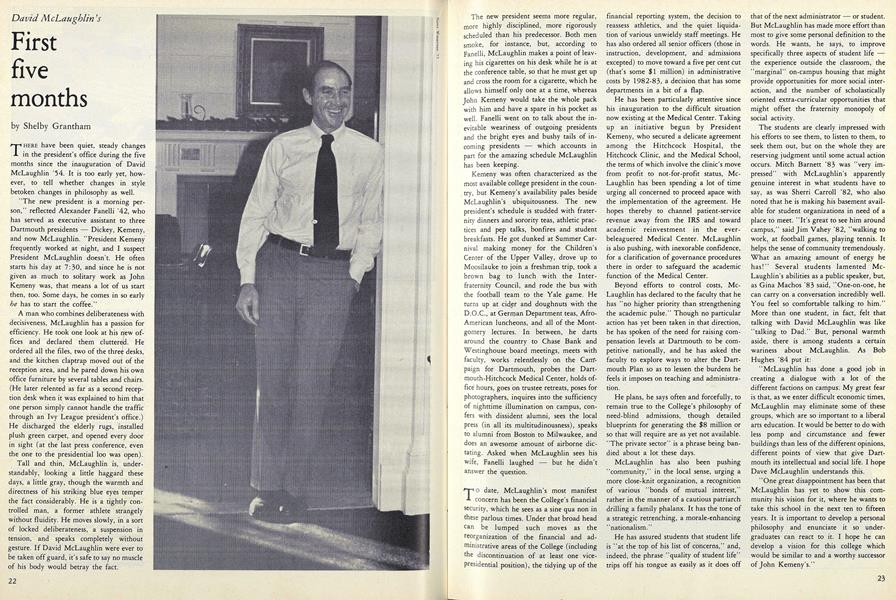

THERE have been quiet, steady changes in the president's office during the five months since the inauguration of David McLaughlin '54. It is too early yet, however, to tell whether changes in style betoken changes in philosophy as well.

"The new president is a morning person," reflected Alexander Fanelli '42, who has served as executive assistant to three Dartmouth presidents Dickey, Kemeny, and now McLaughlin. "President Kemeny frequently worked at night, and I suspect President McLaughlin doesn't. He often starts his day at 7:30, and since he is not given as much to solitary work as John Kemeny was, that means a lot of us start then, too. Some days, he comes in so early he has to start the coffee."

A man who combines deliberateness with decisiveness, McLaughlin has a passion for efficiency. He took one look at his new offices and declared them cluttered. He ordered all the files, two of the desks, and the kitchen claptrap moved out of the reception area, and he pared down his own office furniture by several tables and chairs. (He later relented as far as a second reception desk when it was explained to him that one person simply cannot handle the traffic through an Ivy League president's office.) He discharged the elderly rugs, installed plush green carpet, and opened every door in sight (at the last press conference, even the one to the presidential 100 was open).

Tall and thin, McLaughlin is, understandably, looking a little haggard these days, a little gray, though the warmth and directness of his striking blue eyes temper the fact considerably. He is a tightly controlled man, a former athlete strangely without fluidity. He moves slowly, in a sort of locked deliberateness, a suspension in tension, and speaks completely without gesture. If David McLaughlin were ever to be taken off guard, it's safe to say no muscle of his body would betray the fact.

The new president seems more regular, more highly disciplined, more rigorously scheduled than his predecessor. Both men smoke, for instance, but, according to Fanelli, McLaughlin makes a point of leaving his cigarettes on his desk while he is at the conference table, so that he must get up and cross the room for a cigarette, which he allows himself only one at a time, whereas John Kemeny would take the whole pack with him and have a spare in his pocket as well. Fanelli went on to talk about the inevitable weariness of outgoing presidents and the bright eyes and bushy tails of incoming presidents which accounts in part for the amazing schedule McLaughlin has been keeping.

Kemeny was often characterized as the most available college president in the country, but Kemeny's availability pales beside McLaughlin's übiquitousness. The new president's schedule is studded with fraternity dinners and sorority teas, athletic practices and pep talks, bonfires and student breakfasts. He got dunked at Summer Carnival making money for the Children's Center of the Upper Valley, drove up to Moosilauke to join a freshman trip, took a brown bag to lunch with the Interfraternity Council, and rode the bus with the football team to the Yale game. He turns up at cider and doughnuts with the D.0.C., at German Department teas, AfroAmerican luncheons, and all of the Montgomery lectures. In between, he darts around the country to Chase Bank and Westinghouse board meetings, meets with faculty, works relentlessly on the Campaign for Dartmouth, probes the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, holds office hours, goes on trustee retreats, poses for photographers, inquires into the sufficiency of nighttime illumination on campus, confers with dissident alumni, sees the local press (in all its multitudinousness), speaks to alumni from Boston to Milwaukee, and does an awesome amount of airborne dic- tating. Asked when McLaughlin sees his wife, Fanelli laughed but he didn't answer the question.

T o date, McLaughlin's most manifest concern has been the College's financial security, which he sees as a sine qua non in these parlous times. Under that broad head can be lumped such moves as the reorganization of the financial and administrative areas of the College (including the discontinuation of at least one vicepresidential position), the tidying up of the financial reporting system, the decision to reassess athletics, and the quiet liquidation of various unwieldy staff meetings. He has also ordered all senior officers (those in instruction, development, and admissions excepted) to move toward a five per cent cut (that's some $1 million) in administrative costs by 1982-83, a decision that has some departments in a bit of a flap.

He has been particularly attentive since his inauguration to the difficult situation now existing at the Medical Center. Taking up an initiative begun by President Kemeny, who secured a delicate agreement among the Hitchcock Hospital, the Hitchcock Clinic, and the Medical School, the terms of which involve the clinic's move from profit to not-for-profit status, McLaughlin has been spending a lot of time urging all concerned to proceed apace with the implementation of the agreement. He hopes thereby to channel patient-service revenue away from the IRS and toward academic reinvestment in the everbeleaguered Medical Center. McLaughlin is also pushing, with inexorable confidence, for a clarification of governance procedures there in order to safeguard the academic function of the Medical Center.

Beyond efforts to control costs, McLaughlin has declared to the faculty that he has "no higher priority than strengthening the academic pulse." Though no particular action has yet been taken in that direction, he has spoken of the need for raising compensation levels at Dartmouth to be competitive nationally, and he has asked the faculty to explore ways to alter the Dartmouth Plan so as to lessen the burdens he feels it imposes on teaching and administration.

He plans, he says often and forcefully, to remain true to the College's philosophy of need-blind admissions, though detailed blueprints for generating the $8 million or so that will require are as yet not available. "The private sector" is a phrase being bandied about a lot these days.

McLaughlin has also been pushing "community," in the local sense, urging a more close-knit organization, a recognition of various "bonds of mutual interest," rather in the manner of a cautious patriarch drilling a family phalanx. It has the tone of a strategic retrenching, a morale-enhancing "nationalism."

He has assured students that student life is "at the top of his list of concerns," and, indeed, the phrase "quality of student life" trips off his tongue as easily as it does off that of the next administrator or student. But McLaughlin has made more effort than most to give some personal definition to the words. He wants, he says, to improve specifically three aspects of student life the experience outside the classroom, the "marginal" on-campus housing that might provide opportunities for more social interaction, and the number of scholastically oriented extra-curricular opportunities that might offset the fraternity monopoly of social activity.

The students are clearly impressed with his efforts to see them, to listen to them, to seek them out, but on the whole they are reserving judgment until some actual action occurs. Mitch Barnett '83 was "very impressed" with McLaughlin's apparently genuine interest in what students have to say, as was Sherri Carroll '82, who also noted that he is making his basement available for student organizations in need of a place to meet. "It's great to see him around campus," said Jim Vahey '82, "walking to work, at football games, playing tennis. It helps the sense of community tremendously. What an amazing amount of energy he has!" Several students lamented McLaughlin's abilities as a public speaker, but, as Gina Machos '83 said, "One-on-one, he can carry on a conversation incredibly well. You feel so comfortable talking to him." More than one student, in fact, felt that talking with David McLaughlin was like "talking to Dad." But, personal warmth aside, there is among students a certain wariness about McLaughlin. As Bob Hughes '84 put it:

"McLaughlin has done a good job in creating a dialogue with a lot of the different factions on campus. My great fear is that, as we enter difficult economic times, McLaughlin may eliminate some of these groups, which are so important to a liberal arts education. It would be better to do with less pomp and circumstance and fewer buildings than less of the different opinions, different points of view that give Dartmouth its intellectual and social life. I hope Dave McLaughlin understands this.

"One great disappointment has been that McLaughlin has yet to show this community his vision for it, where he wants to take this school in the next ten to fifteen years. It is important to develop a personal philosophy and enunciate it so undergraduates can react to it. I hope he can develop a vision for this college which would be similar to and a worthy successor of John Kemeny's."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

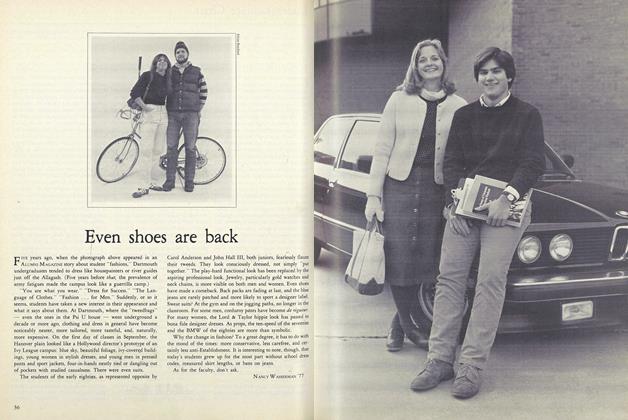

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

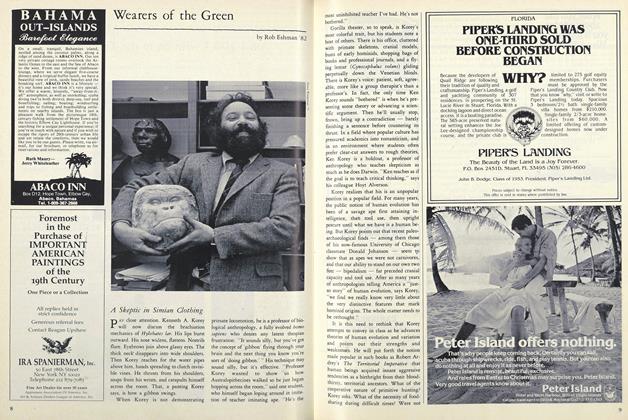

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

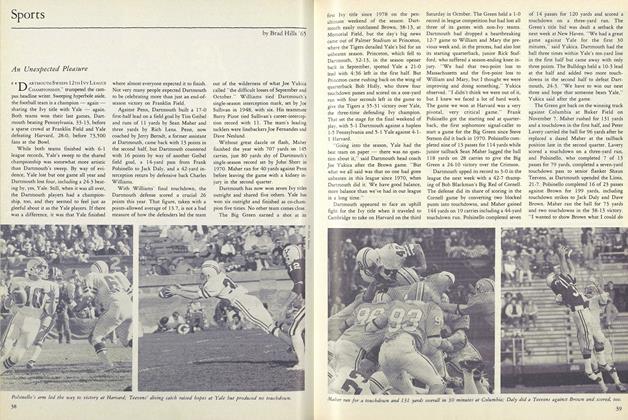

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

December 1981 By Adrian A. Walser

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe conquest of Kiewit (sort of)

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

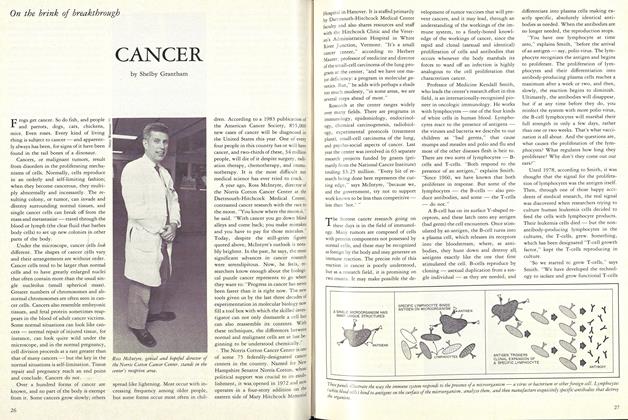

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

JUNE 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWar Memorial Planned in Center

MAY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureCarole Berger Professor of English 2 wolves in a single run

January 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Starscape That Is Just Amazing"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

FeatureJENNIFER LIND

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Blackboard

May 1998 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH IN THE PEACE CORPS

MAY 1963 By Clifford L. Jordan Jr. '45