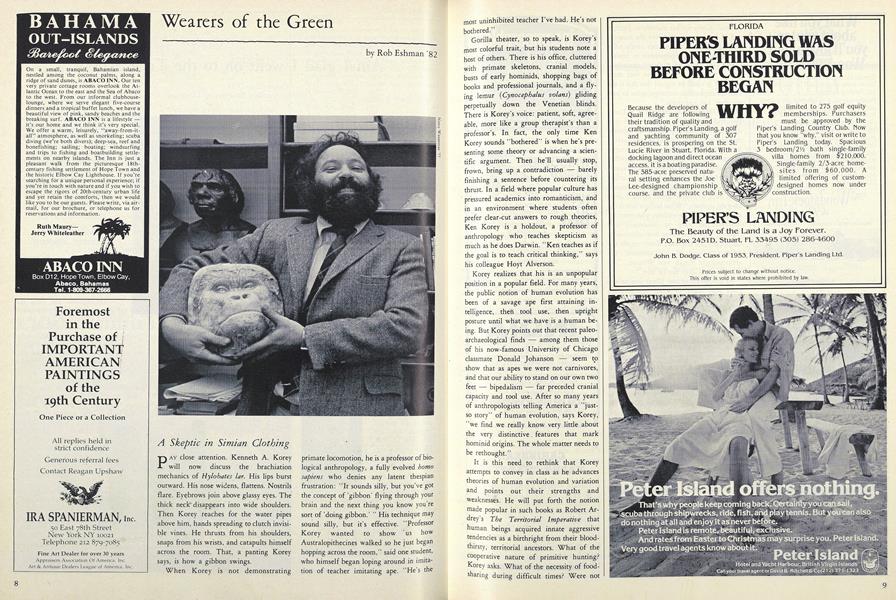

PAY close attention. Kenneth A. Korey will now discuss the brachiation mechanics of Hylobates lar. His lips burst outward. His nose widens, flattens. Nostrils flare. Eyebrows join above glassy eyes. The thick neck disappears into wide shoulders. Then Korey reaches for the water pipes above him, hands spreading to clutch invisible vines. He thrusts from his shoulders, snaps from his wrists, and catapults himself across the room. That, a panting Korey says, is how a gibbon swings.

When Korey is not demonstrating primate locomotion, he is a professor of biological anthropology, a fully evolved homosapiens who denies any latent thespian frustration: "It sounds silly, but you've got the concept of 'gibbon' flying through your brain and the next thing you know you're sort of doing gibbon.' " His technique may sound silly, but it's effective. "Professor Korey wanted to show us how Australopithecines walked so he just began hopping across the room," said one student, who himself began loping around in imitation of teacher imitating ape. "He's the most uninhibited teacher I've had. He's not bothered."

Gorilla theater, so to speak, is Korey's most colorful trait, but his students note a host of others. There is his office, cluttered with primate skeletons, cranial models, busts of early hominids, shopping bags of books and professional journals, and a flying lemur (Cynocephalus volaris) gliding perpetually down the Venetian blinds. There is Korey's voice: patient, soft, agreeable, more like a group therapist's than a professor's. In fact, the only time Ken Korey sounds "bothered" is when he's presenting some theory or advancing a scientific argument. Then he'll usually stop, frown, bring up a contradiction - barely finishing a sentence before countering its thrust. In a field where popular culture has pressured academics into romanticism, and in an environment where students often prefer clear-cut answers to rough theories, Ken Korey is a holdout, a professor of anthropology who teaches skepticism as much as he does Darwin. "Ken teaches as if the goal is to teach critical thinking," says his colleague Hoyt Alverson.

Korey realizes that his is an unpopular position in a popular field. For many years, the public notion of human evolution has been of a savage ape first attaining intelligence, then tool use, then upright posture until what we have is a human being. But Korey points out that recent paleoarchaeological finds - among them those of his now-famous University of Chicago classmate Donald Johanson-seem to show that as apes we were not carnivores, and that our ability to stand on our own two feet-bipedalism - far preceded cranial capacity and tool use. After so many years of anthropologists telling America a "justso story" of human evolution, says Korey, "we find we really know very little about the very distinctive, features that mark hominid origins. The whole matter needs to be rethought."

It is this need to rethink that Korey attempts to convey in class as he advances theories of human evolution and variation and points out their strengths and weaknesses. He will put forth the notion made popular in such books as Robert Ardrey's The Territorial Imperative that human beings acquired innate aggressive tendencies as a birthright from their bloodthirsty, territorial ancestors. What of the cooperative nature of primitive hunting? Korey asks. What of the necessity of foodsharing during difficult times? Were not these behaviors more integral to our species' survival? Korey teaches students to question and, if necessary, discard even the most ingrained theories. Yet he can rarely offer more than a rough hypothesis to replace them. "It's judicious to leave unresolved certain questions until we can find more evidence. It could be argued that this is the time for responsible anthropologists to button their lips and think."

Some students say they leave a Korey class frustrated, not having been given anything but shattered hypotheses and tentative theories. Alverson defends Korey, saying there is a "bottom-line mentality" among such students that demands hard facts when none may truly exist. Korey remains as uninhibited about doubt as about acting simian: "It's very hard to sell uncertainty, but I have no qualms about saying I don't have the answers." What bothers him is the attitude among some students who yearn for "information easy to memorize and classify," and who accept that information uncritically. In response, Korey recalls the words of one of his mentors, the anthropologist Leigh van Whelan: "All that we know may not be true."

As an undergraduate, Korey says he was more than eager to accept the concrete answers offered him as a "science jock." He entered the University of Chicago's graduate M.D.-Ph.D. program in biology and mathematics. While he was tutoring some anthropology students on the computer, Korey recalls, "It readily became apparent that what they did was more interesting than what I was doing." The chance anthropology presented to "think new thoughts," combined with young Korey's romantic view of anthropology as "the academic navy - sign up and see the world," led him to physical anthropology, the study of human evolution and variation. He completed graduate work at Chicago, did some field studies in the high Arctic and Great Britain ("I discovered the first Pleistocene beaver in Britain"), and arrived at Dartmouth in 1972. The Anthropology Department at Dartmouth is a relatively small college department, but Korey feels it adds an important "holistic" dimension to the curriculum. Anthropology provides an "interlocked view of culture from an evolutionary perspective," useful to those whose lives will involve cultures outside their own. As Korey says and as rising department enrollment figures seem to indicate - that includes us all.

From a "pre-med weenie" trained in gross anatomy and computer science, Korey has become the acting chairman of the department. In the process, he has changed from someone who had been a "trading post for other's ideas" to someone who senses a "higher obligation" to students than providing pat answers to complex questions. This tendency toward skepticism comes through in his professional papers, too. Alverson says Korey has made "signal contributions" to the field through his analyses of current research methodologies. Though his topics range from skin-color variation to animal mastication, Korey sees all of them as serving a "gadfly" function in his discipline. One of these papers, which has secured Korey a respected place among his national and international colleagues, came about as a result of a class session in which both teacher and students discovered a flaw in the a logic of a well-known anthropological proof. "I had heard about the cross-fertilization of teacher and students, but that was amazing." The discovery helped settle a decade-long argument between molecular biologists and paleontologists over the rate of evolutionary change. The skepticism Korey emphasizes paid off.

A Korey exam is as frustratingly demanding of the students' ability to associate different evolutionary "clues," criticize theories, and explore ramifications as a Korey class. "You can't study for them," muttered one student, "you have to think." When I interviewed Korey he had just finished grading midterms and had found that freshmen scored higher than upperclassmen. Was that because freshmen were better able to think imaginatively than upperclassmen, who may have become accustomed to filling up with facts and pouring them out on exams? Korey winced: "Oh, no, do you think so? That would be frightening. If that were true, I'd say we owed you all some tuition:"

Does what Alverson calls Korey's "strenuous moral exercises and intense intellectual integrity" spill over into Korey's family life? Korey laughs. He and his wife Jane, a Ph.D. candidate in cultural anthropology at Brandeis University, have two preschool-aged children, Julia and Margaret. When Julia started to ask questions about death, Korey began offering the stock "we'll-all-get-together-on-theother-side" explanations. Then he checked himself: How could he give his children such pat answers? Welcome to the Korey classroom, Julia.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

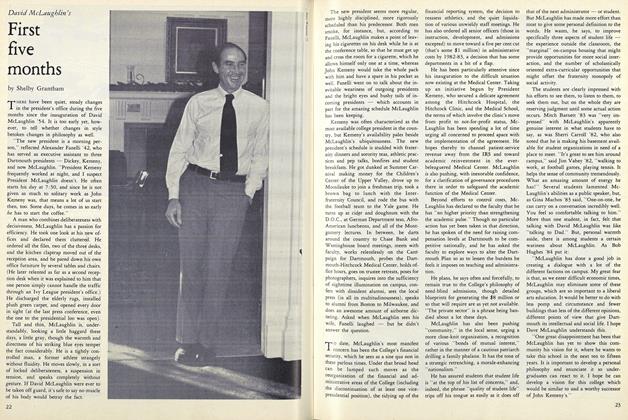

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

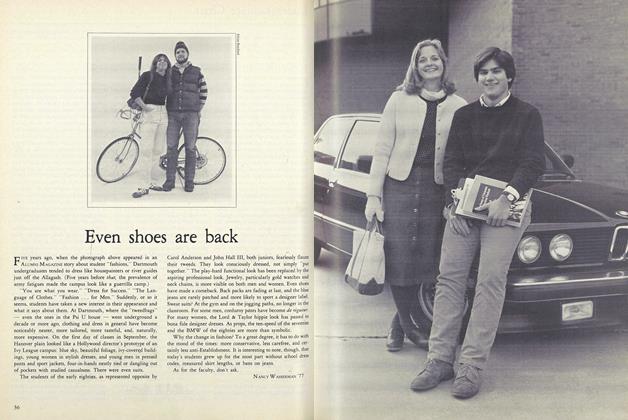

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Sports

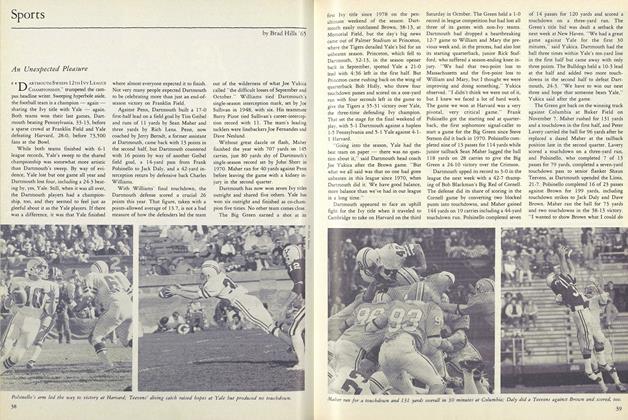

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

December 1981 By Adrian A. Walser

Rob Eshman '82

-

Article

ArticleA Time Away

OCTOBER 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Article

ArticleTo Play Is to Lose

DECEMBER 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

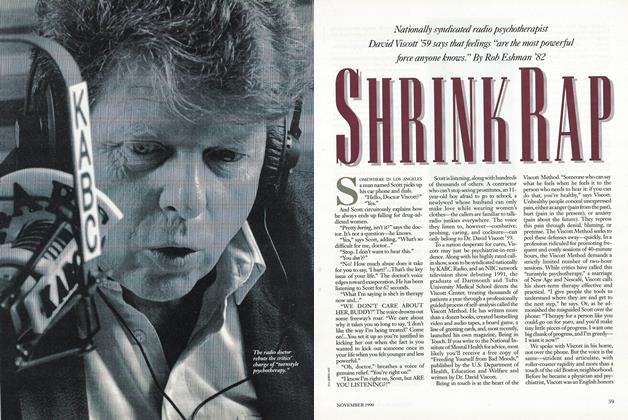

FeatureShrink Rap

NOVEMBER 1990 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ascent of Korey

MARCH 1995 By Rob Eshman '82

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

April, 1915 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ROLL OF HONOR

January 1919 -

Article

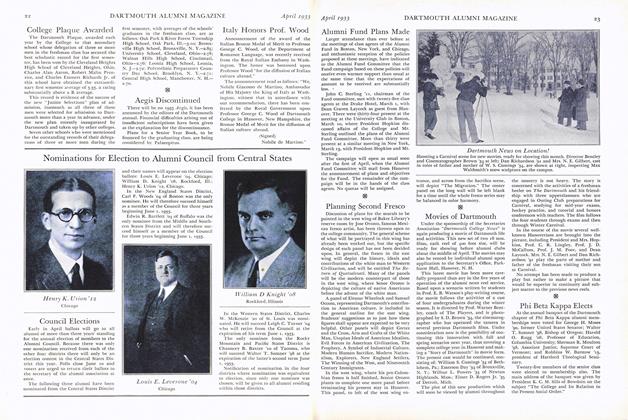

ArticleCollege Plaque Awarded

April 1933 -

Article

ArticleValedictory to All-Star Class Agents

January 1943 -

Article

ArticleLECTURES WERE RARE

DECEMBER 1929 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett -

Article

ArticleAre You Looking for Work?

June 1937 By WILLIAM L. FLETCHER '14