How do you stop 24,000-percent inflation? The hard way, says the Dartmouth-bred finance minister of Bolivia.

FINANCE Minister Juan Cariaga has a simple formula for ensuring that Bolivia doesn't return to the night-marish days of a 24,000-percent inflation rate. Every morning, the 1969 Dartmouth graduate in economics receives a computer printout showing how much money the cash-strapped government has available. He then authorizes paying civil service salaries and other government debts due that day until the available funds are gone. "If we don't have the money, we don't meet our obligations that day," Cariaga says with a smile. "We won't spend what we don't have."

That hard-nosed philosophy is at the core of perhaps the most sweeping free-market economic program ever adopted in Latin America. Like most countries in this region, Bolivia has traditionally believed that the path to economic growth is a governmentdirected economy. Bolivian President Hernan Siles Zuazo, whose 1982-85 term ended 18 years of military rule, carried to an excess a faith in government's ability to do good. Responding to pent-up demand for public expenditures, he printed money at an astonishing pace and thus sparked the 24,000-percent annual inflation rate, the seventh highest for any nation in world history and the only hyperinflation not caused by war or revolution. At the same time, from 1980 to 1985 the economy contracted by 25 percent.

Current President Victor Paz Estenssoro, implementing a plan that Cariaga helped devise, is dramatically changing the government's role here— and in the process is carrying out an economic revolution so far-reaching that it puts the so-called Reagan Revolution to shame. Along with ending hyperinflation and trying to revive growth, Paz, 79, is also seeking to practically reinvent the country's economy, which for years relied on tin to provide 75 percent of the country's legal export income.

Following a 66-percent drop in tin prices in October 1985, Paz, Cariaga and other government ministers are betting that ending the state's traditional heavy intervention in the economy will unleash a flurry of entrepreneurial activity that will generate enough income to replace tin exports.

They know that if their plan fails to produce positive results within the next year, the military may step in, as it has done dozens of times since Bolivia won its independence in 1825. In the meantime, while the country undergoes the painful transition from its reliance on tin, the economy has become dependent on dollar income from cocaine smuggling, as Cariaga admits with embarrassment.

Although he wasn't named finance minister until January 1986, Cariaga has played a key role in economic policymaking from the beginning (see the box at right). The most important action the revolutionary economic program took after President Paz assumed office in August 1985 was to float Bolivia's peso and to stop the printing presses, which were running day and night. These two steps together caused the peso, which had been devaluing hourly to keep pace with the spiralling inflation rate, to stabilize at approximately two million per dollar, where it has remained since then.

In conjunction, the government slashed tariffs and lifted controls on prices and interest rates. To reduce a budget deficit that had reached 25 percent of gross domestic product, Paz fired thousands of government employees, froze the wages of those kept on, raised state gas prices tenfold and imposed a ten-percent value-added tax. When tin prices plummeted, the government once again displayed its hardheaded approach to economic management by laying off 23,000 of the state tin mining company's 30,000 miners.

So far, the economic program has achieved notable successes. The strict monetarist program has caused inflation to plummet to ten percent, and the economy will grow by 2.2 percent in 1987, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), marking the first growth in seven years. As an added, mixed blessing, Bolivia's underground economy, which accounts for as much as 60 percent of economic activity, appears to be more vibrant than before.

But the cost of reshaping Bolivia's economy has been high, and both businessmen and the powerful Marxist-dominated labor unions have bitterly criticized the government. Demonstrations by ex-miners, teachers and students are so common that riot police are almost a daily sight on La Paz's cobblestone streets.

Even more alarming to Cariaga is an increasingly restive private sector. After years of calling on Bolivian governments to adopt free-market policies, businessmen are now saying that Paz and Cariaga went too far in eliminating a plethora of subsidies to which they had grown accustomed. The business leaders warn that if the government doesn't raise import tariffs on goods already produced in Bolivia and reestablish minimum price supports for agricultural products, many companies will go bankrupt.

Cariaga even faces pressure from politicians within the president's party who have traditionally expected finance ministers to hand out favors. In a highly political country, Cariaga is an apolitical independent. Before heading the Banco de Santa Cruz's La Paz office for nine years, he worked as a World Bank consultant in Washington and served as a diplomat in Bolivia's embassy there. Recently, in a politically risky gesture, he was critized by several other ministers when he imposed a $15,000 limit on the cars each was allowed to purchase for official use. "If we're going to ask the Bolivian people to sacrifice, we're going to have to be austere ourselves," he explains.

Unpopular in Bolivia, the government not surprisingly has won strong backing from the Reagan Administration for its market-oriented economic moves. "Cariaga deserves a great deal of credit for putting together an effective stabilization program in Bolivia," says Jeff Biggs, Deputy Chief of Mission at the U.S. embassy in La Paz.

While the government waits for a burst of entrepreneurial activity that will reflate the economy, the country remains afloat thanks to several hundred million dollars in loans from the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank and the IMF. These institutions enthusiastically back Bolivia's economic prescription.

At the same time, the economy depends on the country's flourishing cocaine business, which supplies almost 40 percent of the U.S. market. Illegal exports of the drug will generate an estimated $600 million this year, equal to total legal exports. The livelihood of as many as 500,000 Bolivians depends on cocaine. Santa Cruz and Cocha-bamba, the country's second and third biggest cities, are dotted with drug traffickers' houses, conspicuous for their garish architecture and electronic security systems.

Dollars earned from the cocaine trade are so vital to the nation that Cariaga initially questioned President Paz's decision in mid-1986 to invite 160 U.S. troops in an attempt to knock out the drug trade. "I was very worried," Cariaga says, recalling his fear that a cutoff in cocaine dollars would ruin his economic program. But the U.S. troops dried up demand for coca leaves only briefly during their four-month stay, and the Central Bank had enough dollars in reserve to absorb the minimal dollar loss.

Cariaga now says, "I agree with the president that we have to stamp out the cocaine trade. If we don't, someday we may have a cocaine president." Noting that cocaine paste addiction among Bolivian youths is rising at an alarming rate, he adds, "I hate to think that one day one of my children could get hooked on drugs."

Still, the economy is Cariaga's biggest passion for the time being. Born and raised in La Paz, which at 12,000 feet above sea level is the world's highest capital city, he went on after Dartmouth to earn a master's degree at Rutgers. But he says it was Dartmouth's Economics Department that first exposed him to the free-market economic philosophy he is implementing in this country of 6.5 million residents. "Professor Colin Campbell was very influential," says Cariaga, who graduated a year ahead of his class, referring to the Loren M. Berry Professor of Economics who has preached the free-market gospel for years.

The son of a travel agent, Cariaga came to Dartmouth by chance. After graduating from a Bolivian high school, he applied for a scholarship from the Institute of International Education to study in the United States. Several months later he received a letter saying that not only had he won a scholarship but that Dartmouth had accepted him. "I had never heard of Dartmouth, so I showed the letter to an American neighbor," Cariaga recalls. "He said to me, 'You're very lucky; you've been selected by one of the most prestigious universities in the U.S.' "

Although leftist political leaders regularly denounce "Yanqui Imperialism," no one makes an issue of Cariaga's Ivy League background. In a country where only one percent of the population graduates from college, his Dartmouth degree has helped him gain entrance into Bolivia's social and political elite. (He is only one of a sizable number of government ministers in Latin America with an Ivy League education.)

Living in Bolivia, the poorest and most underdeveloped country in South America with an annual percapita income of $400, has reinforced the economic views he acquired at Dartmouth. Only a fraction of the country's roads are paved, and thousands of children die from malnutrition every year. The underemployment rate is some 60 percent. "Bolivia has been a permanent economic disaster," he says. "Decisions have always been made by a few government bureaucrats who thought they knew all the answers." Cariaga himself does not act like a bureaucrat. He is the only minister in Bolivia who drives his government-issue car, a gray Toyota compact.

While Cariaga clearly relishes playing a key role in reshaping Bolivia's economy, he admits to feeling the pressures from the job. "I worry about whether the decisions I make will be good or bad," he says, noting that the gray in his beard and hair has appeared only in the past 18 months. "If I make a mistake, the whole country will suffer." He also wearies of the latenight meetings, the early morning phone calls and the little time he has to spend with his family. "This job is a disaster for a marriage," says Cariaga, who was divorced in 1981 and remarried two years ago.

What does a Dartmouth grad do after wielding enormous power as finance minister? Cariaga says he would like to resume teaching—he taught at La Paz's Catholic University and has authored several textbooks—and perhaps become a consultant to international lending institutions and development agencies. He plans to remain in Bolivia.

But he muses about the possibility of spending a year as a visiting professor at Dartmouth. Certainly, he would bring a unique background. How many professors can discuss their experience in helping stop a 24,000-percent inflation rate and trying to end a nation's economic dependence on cocaine? But in the meantime, there is much work to do in carrying out a revolution that he believes will right an economy gone wrong.

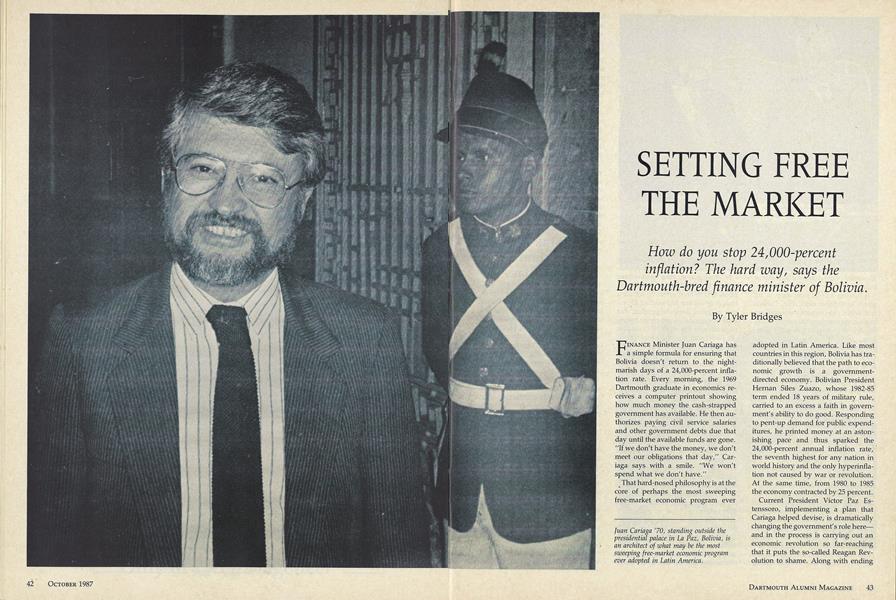

Juan Cariaga '70, standing outside thepresidential palace in La Paz, Bolivia, isan architect of what may be the mostsweeping free-market economic programever adopted in Latin America.

The finance minister sits with President Victor Paz Estenssoro. If thegovernment fails to revamp Bolivia's economy, the military may step in

Last July, the government presented its economic plan in a nationalbroadcast. Cariaga spoke as long as the other six ministers combined—andworried afterward that he had stolen their thunder.

Work mars the private life of Cariaga, shown with son Diego. "A familydeserves time and attention, but this is not something I'm giving," he says.

The plan is unpopular, but Cariaga insists an unencumbered market is Bolivia's best hope.

"If I make a mistake,"says Cariaga, "the wholecountry will suffer."

Tyler Bridges is a freelance writer travelling and writing in South America. He interviewed Cariaga and Aguirre in Bolivialast summer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

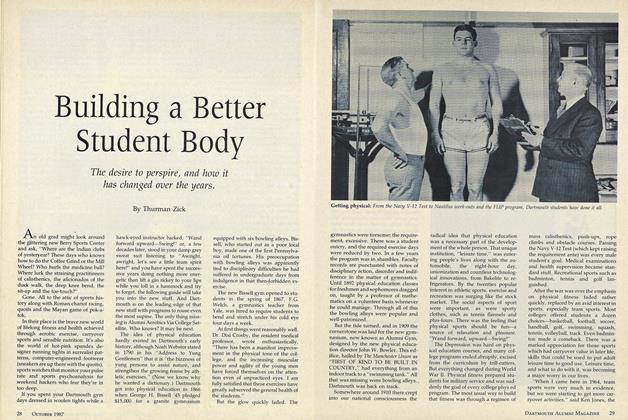

FeatureBuilding a Better Student Body

October 1987 By Thurman Zick -

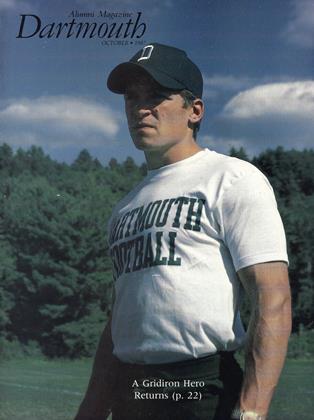

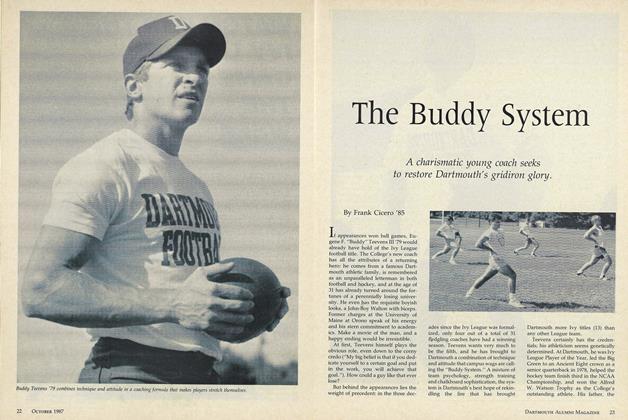

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Buddy System

October 1987 By Frank Cicero '85 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Glory?

October 1987 By Ted Leland -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Gym Scrapbook

October 1987 By Gil Williamson -

Feature

FeatureBad Things You Learned in Gym

October 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

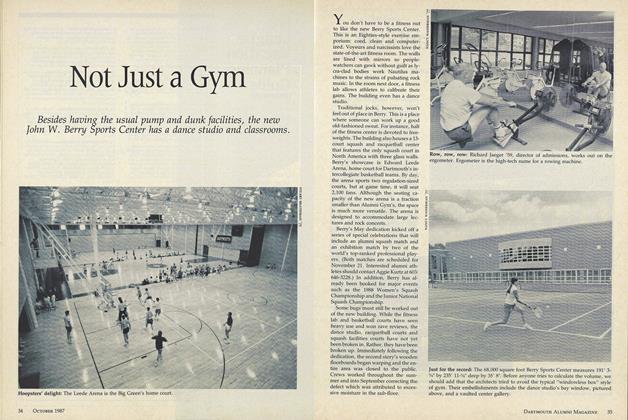

FeatureNot Just a Gym

October 1987

Features

-

Feature

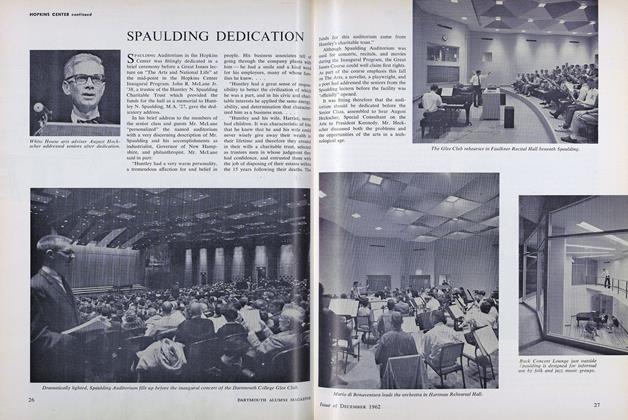

FeatureSPAULDING DEDICATION

DECEMBER 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBruce Allyn '80

March 1993 -

Feature

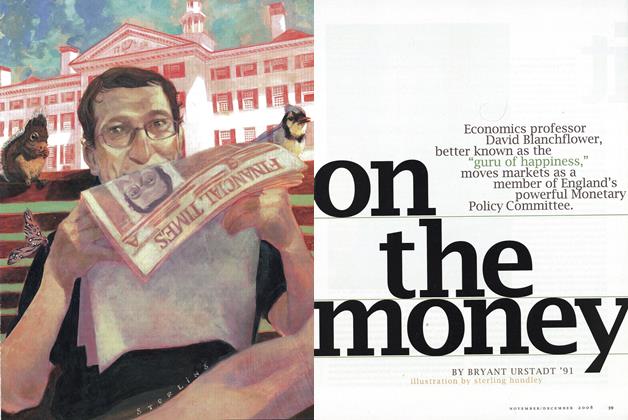

FeatureOn the Money

Nov/Dec 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

FeatureBattle Scarred

Sep - Oct By JAMES WRIGHT -

Feature

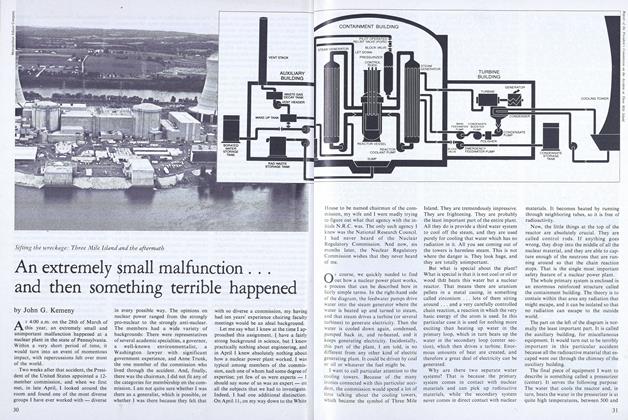

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

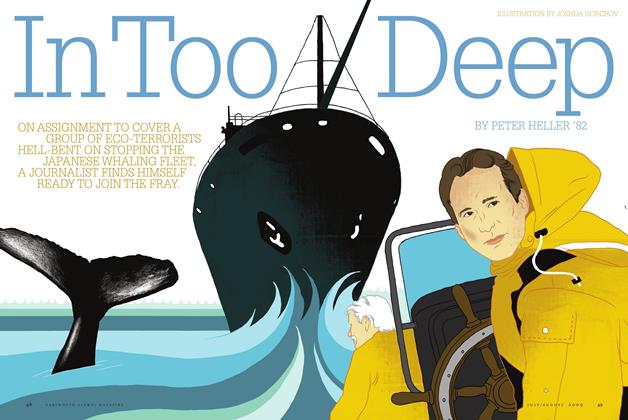

FeatureIn Too Deep

July/Aug 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82