THE ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR IN THE NEAR EAST: Great Power Conflict and Diplomacy in Iran, Turkey, and Greece. By Bruce Kuniholm '64 Princeton, 1980. 485 pp. Softcover, $10.50

As World War II drew to a close with the Red Army firmly in control of Eastern Europe, it proved impossible to prevent the absorption of that area into the Soviet bloc. However, in spite of the post-war collapse of British power and influence in the Near East, in spite of clear Soviet expansionist ambitions in the area, and in spite of the fragile nature of the post-war regimes in Greece, Turkey, and Iran, the Iron Curtain was not dropped across the "Northern Tier" (as Greece, Turkey and Iran came to be known). This was due largely to the Truman dministration's realization that only the prudent application of American power, not highminded slogans, could preserve these countries against Soviet military, political, and economic pressure.

The Origins of the Cold War in the NearEast is a richly documented and powerfully written narrative describing the evolution of American foreign policy in this crucial area from 1945 to 1947, as Washington first awakened to, and then sought means to counter, Soviet encroachments. From disappointment, through crisis and intricate diplomacy, to a policy of firm commitment, Bruce Kuniholm shows how the struggle over the fate of Greece, Turkey, and Iran served to educate American statesmen to the harsh realities of post-war power politics.

The book places the delicate situations in the Northern Tier countries in 1945-1947 in their historical contexts and demonstrates that Soviet-American competition in the area was a natural extension of centuries of great power rivalry mainly between Great Britain and Russia. Then it examines closely British and American reactions to Soviet-supported guerrilla activity in Greece, Russian territorial demands and threats against Turkey, and the Soviet Union's prolonged occupation of Northern Iran. Kuniholm reveals a pattern of reluctant appreciation in the West that the Grand Alliance against Hitler would not survive the peace and that Great Britain was no longer strong enough to be delegated responsibility for Western security interests in the eastern Mediterranean and Persian Gulf.

One of the many virtues of the book is the great care given to the reconstruction of intricate diplomatic problems. Though such an effort might be expected to overwhelm the reader with unassimilable detail, such is not the case. Instead, one is led to grasp the difference that the keen analysis of savvy diplomats can make to success or failure in foreign policy.

When so much of what the United States tries to accomplish abroad these days runs afoul of forces and events that seem beyond our control, it is heartening and instructive to learn of an important political arena in which American foreign policy preserved, if it did not eternally secure, our interests and the prospects for democratic government.

But Kuniholm also warns overly enthusiastic readers against taking Truman's successful containment of Soviet expansion along the Northern Tier as signaling the wisdom, of vigorously asserting American power around the world. Indeed, it was the very success of the Truman Doctrine, Kuniholm contends, that led American policy-makers astray in their search for an appropriate response to instability in Southeast Asia. From 1945 to 1947 Washington learned how to conduct 20thcentury diplomacy with the Soviets according to the rules of 19th-century power politics. This was a rude awakening for a country that believed the defeat of the Axis powers would usher in an age of international law and global collective security. It is perhaps an even ruder awakening to find that rules for conducting a successful foreign policy in the 1980s have never been written.

A specialist in the Near East, lan Lustick is anassistant professor of government.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

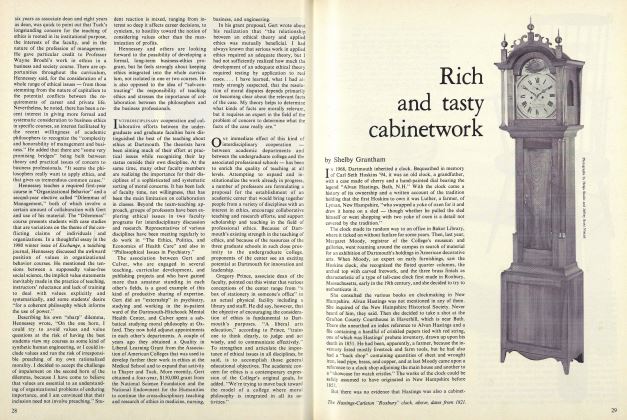

FeatureRich and tasty cabinetwork

March 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

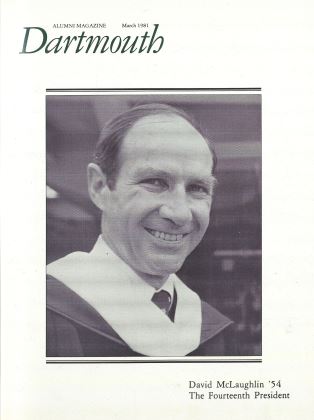

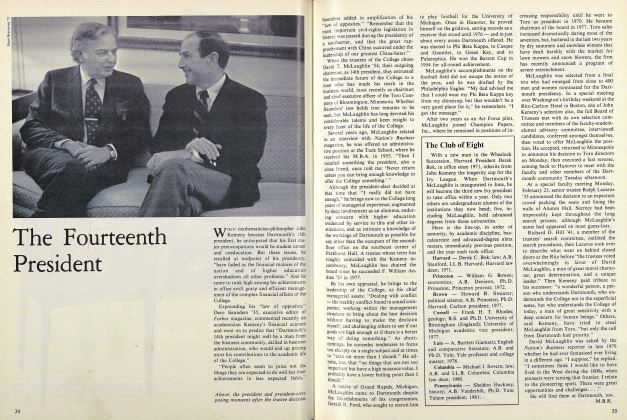

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleImagining Beyond Limits

March 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1981 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1967

March 1981 By CLEMSON N. PAGE, JR.

Books

-

Books

Books"The Technology of New York State Timbers"

APRIL, 1927 -

Books

BooksRobert S. Monahan '29

January, 1931 -

Books

BooksPOEMS.

January 1958 By DILYS LAING -

Books

BooksAUBURN, NEW HAMPSHIRE 1719-1969.

APRIL 1971 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Books

BooksTHE RUSSIANS IN FOCUS

October 1953 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Books

BooksFAINTING.

April 1951 By SVEN M. GUNDERSEN, M.D.