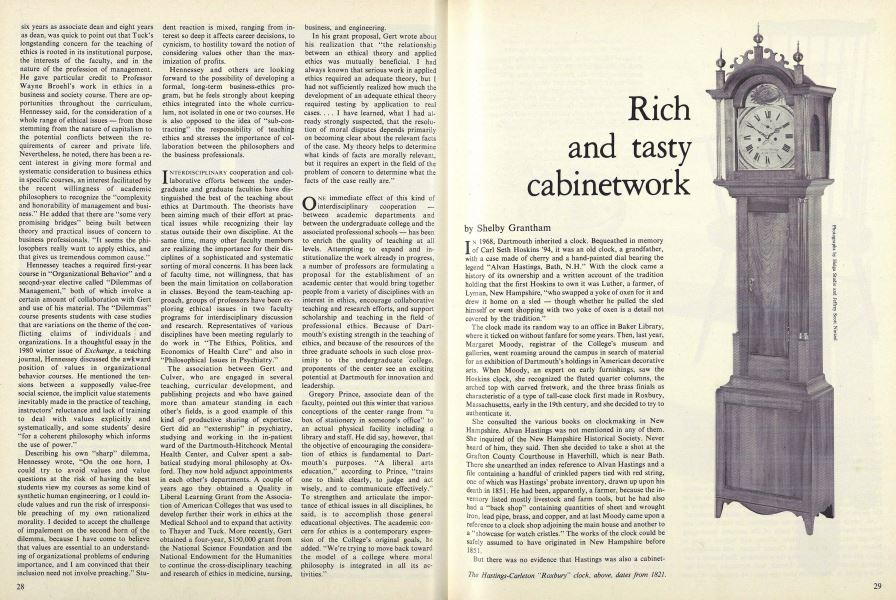

In 1968, Dartmouth inherited a clock. Bequeathed in memory of Carl Seth Hoskins '94, it was an old clock, a grandfather, with a case made of cherry and a hand-painted dial bearing the legend "Alvan Hastings, Bath, N.H." With the clock came a history of its ownership and a written account of the tradition holding that the first Hoskins to own it was Luther, a farmer, of Lyman, New Hampshire, "who swapped a yoke of oxen for it and drew it home on a sled though whether he pulled the sled himself or went shopping with two yoke of oxen is a detail not covered by the tradition."

The clock made its random way to an office in Baker Library, where it ticked on without fanfare for some years. Then, last year, Margaret Moody, registrar of the College's museum and galleries, went roaming around the campus in search of material for an exhibition of Dartmouth's holdings in' American decorative arts. When Moody, an expert on early furnishings, saw the Hoskins clock, she recognized the fluted quarter columns, the arched top with carved fretwork, and the three brass finials as characteristic of a type of tall-case clock first made in Roxbury, Massachusetts, early in the 19th century, and she decided to try to authenticate it.

She consulted the various books on clockmaking in New Hampshire. Alvan Hastings was not mentioned in any of them. She inquired of the New Hampshire Historical Society. Never heard of him, they said. Then she decided to take a shot at the Grafton County Courthouse in Haverhill, which is near Bath. There she unearthed an index reference to Alvan Hastings and a file containing a handful of crinkled papers tied with red string, one of which was Hastings' probate inventory, drawn up upon his death in 1851. He had been, apparently, a farmer, because the inventory listed mostly livestock and farm tools, but he had also had a "back shop" containing quantities of sheet and wrought iron, lead pipe, brass, and copper, and at last Moody came upon a reference to a clock shop adjoining the main house and another to a "showcase for watch cristles." The works of the clock could be safely assumed to have originated in New Hampshire before 1851.

But there was no evidence that Hastings was also a cabinetmaker, and the problem of the case remained. It reminded Moody of another tall-clock case known to have been made by Dudley Carleton of Haverhill. She examined the Hoskins case carefully and discovered, pasted over the arched hood, a dusty, almost illegible page from the New Hampshire Post & Graftonand Coos Intelligencer of some indecipherable date in 1821. The Baker Library files for the Intelligencer of 1821 were discouragingly incomplete, but Moody persisted, and finally, in the issue for April 11, 1828, she turned up a remarkable woodcut depicting a clutch of fashionable furniture as part of an ad for Carleton and Tracy's warehouse in Haverhill, which offered to the public a fine selection of "rich and tasty cabinet furniture."

So, newly explained, into the exhibition the clock went, and Moody moved on to other parts of the campus, rummaging through storage areas, private offices, and locked rooms in Baker, Sanborn House, and Choate House, and poking into likely private homes, including the president's. She located a surprising amount of English, French, and American period furniture given to Dartmouth over the past two centuries, in most cases by alumni and professors. Moody distilled from what she found a collection of 34 exemplary American-made pieces dating from the 18th and 19th centuries. To them she added 16 pieces from Dartmouth's small but outstanding collection of 18thcentury silver, and the result "American Decorative Arts at Dartmouth" has captured more than the local imagination. The exhibition opened in January at Hopkins Center to a record attendance for a gallery event there, and soon after, TheMagazine Antiques announced it would feature the exhibition in its May issue.

With this exhibition, Dartmouth enters the ranks of serious collectors of decorative arts silver, pewter, glass, ceramics, and furniture. "Utilitarian objects of exemplary design and craftsmanship," as Moody explained it. "In previous years," she went on to point out, "handmade furniture did not have the same status at Dartmouth as paintings or sculpture, so that gifts of furniture weren't always dated and catalogued with the same care." She spent over a year ferreting out and documenting the pieces in her- exhibition, and she had woeful tales to tell of whole households of fine furniture (such as that of Anton Raven, professor of English at the College) received by Dartmouth as bequests and then sold off without even being appraised. Other gifts of furniture were kept but were thoughtlessly put into general use, such as the inlaid Federal card table Moody discovered under a student's feet in Sanborn House and the 1817 tall-case clock she found at Thayer Hall, missing a hand and its face-glass, both having disappeared during the years of hard partying it saw as a fixture at the Outing Club House.

One of the most remarkable groups in the exhibition is a selection of early 19th-century furniture first owned by George Ticknor of the class of 1807. In 1829, Ticknor, a prominent Harvard professor of French and Spanish, furnished his new house on Boston Common with the latest in French-influenced Empire furniture, of which he was very proud. (Ticknor once visited Thomas Jefferson in Virginia and wrote home to say he didn't think much of the furniture at Monticello.)

Ticknor died in 1871, and in 1946 his descendants bequeathed to Dartmouth the contents of his entire library furniture, books, papers, even the draperies and the mantlepiece. The furniture went into storage, and the cataloguer who handled it, mistakenly attributing it to the 20th century, insured it for ridiculously low figures: The most expensive item in the insurance listing was $25. Finally, in 1966, Thomas W. Streeter "04, whose grandson was George Ticknor's great-great-great-grandson, gave the College some money to bring the furniture out of storage and install it permanently in Baker Library, in a room now known as the Ticknor Room. The group includes chairs, a secretaire a abattant, a sewing table, firescreen, two magnificent pier tables, card tables, a center table, a Grecian sofa all examples, according to Moody, of superb Boston high-style craftsmanship.

What Moody regards as the most exciting single piece in the exhibition very nearly slipped through her fingers. When the Friends of Hopkins Center sponsored a public antique appraisal last summer, during which the appraising services of an international auction house were made available (for a fee) to anyone with an old article thought to be valuable, Moody attended it, thinking she might hear of something for the exhibition. An officer of the College brought over for inspection photographs of an intricately inlaid sideboard recently left to Dartmouth by the late Philip Chase '07. Moody noticed the photographs and, perking up her ears, did a little eavesdropping.

She heard that the sideboard was then in a reception room of the National Archives in Washington, where it had been on loan for some years. The National Archives people were very interested, said the officer, in buying the sideboard, and, said the officer, the College was very interested in selling it. The appraiser opined that it was probably a Baltimore piece and worth, perhaps, some $12,000.

Moody, however, saw in the photographs some details suggesting to her that the handsome piece might have originated in the Connecticut River Valley, and she decided to ask a colleague in Washington to go and have a look at it for her. The colleague called back with the information that it could very likely be a Connecticut River Valley sideboard and that furthermore it had once belonged to the first treasurer of Dartmouth College, Mills Olcott of the class of 1790.

The news of a historical connection with Dartmouth spurred Moody to make a determined effort to prevent the sale of the sideboard. She spent several frantic days wading through what seemed like endless red tape trying to locate the officials with the authority to decide both to keep the piece and to allow its use in the exhibition, but she was, in the end, successful. The sideboard was carefully crated and tenderly transported to Hanover last December, just in time to become the centerpiece for the exhibition. With a little digging, Moody was able to trace its history and to attribute it to Julius Barnard, a cabinetmaker of Northampton, Massachusetts, who set up shop in Hanover for a single year 1801.

The College's collection of American decorative arts is young yet, said Moody, and it has some gaps. She turned up, for instance, no American furniture from the 17th century. There were some 17th-century chests, and a chair, but they all proved to be English. The earliest pieces are from the period 1730-50, and even then. Moody explained, not every form is represented: "We have no chairs, for instance, from the period of William and Mary or from the Federal period; and the only Chippendale chair in the collection has proved to be a very fine Centennial reproduction. We have only a couple of pieces of glass, one or two examples of pewter, and a few, mostly chipped, ceramic pieces." The furniture on exhibit (most of it from the first quarter of the 19th century) includes the Queen Anne "Eleazar" armchair (thought to have belonged to Dartmouth's first president), a cherry chest-on-chest, Grecian couches, Boston Empire chairs, and a desk owned by the father of Daniel Webster.

"The strength of this collection," said Moody, "lies in its examples from northern New England. The exhibition demonstrates that sophisticated designs and quality workmanship were available in this rural region and that local cabinetmakers could produce as elegant a piece as could be had from Boston or New York. I would like to see us concentrate on collecting more good examples of New Hampshire and Vermont craftsmanship, about which not much is known yet." Her hope is that her work in organizing Dartmouth's current holdings will spur the growth of the collection by alerting people within and without the College to its existence and to its aesthetic, its historical, and, of course, its monetary value. "Although," she concluded with a worried look around the tiny gallery storeroom, "right now 1 don't know where we would put more furniture."

The Hastings-Carleton "Roxbury" clock, above, dates from 1821.

Windsor chairs were introduced to this country inPhiladelphia about 1750. The one on the left, said tohave belonged to Asa Burton of the class of 1777, wasmade about 1800 of ash and white pine, probably inVermont, and it bears several layers of original paint.The silver porringer below, dated 1731, was made byPaul Revere I (born Apollos Rivoire), the Huguenotwho learned the silver trade in Boston and later passedit on to his son Paul, the patriot.

Windsor chairs were introduced to this country inPhiladelphia about 1750. The one on the left, said tohave belonged to Asa Burton of the class of 1777, wasmade about 1800 of ash and white pine, probably inVermont, and it bears several layers of original paint.The silver porringer below, dated 1731, was made byPaul Revere I (born Apollos Rivoire), the Huguenotwho learned the silver trade in Boston and later passedit on to his son Paul, the patriot.

When the China trade brought tea toAmerica in the 18th century, it becamevery popular, despite its expense, and soonspecial pots for storing, brewing, and serving tea were found in almost everyhousehold. The silver teapot on the rightwas made by Jacob Hurd, an early Bostonsilversmith, in 1745. It was a gift to H.Fayerweather and is engraved with theFayerweather coat of arms. Below is oneof a pair of Ticknor pier tables in Dartmouth's collection. It was made in Bostonaround 1820, of mahogany, chestnut, andwhite pine with highly figured mahoganyveneers. Such tables, designed to fill thewall spaces between pairs of windows, werecharacterized by columnar legs, marbletops, and mirrored back panels, and thisone is accented by ormolu caps, bases, anddecorative mounts probably imported fromFrance.

When the China trade brought tea toAmerica in the 18th century, it becamevery popular, despite its expense, and soonspecial pots for storing, brewing, and serving tea were found in almost everyhousehold. The silver teapot on the rightwas made by Jacob Hurd, an early Bostonsilversmith, in 1745. It was a gift to H.Fayerweather and is engraved with theFayerweather coat of arms. Below is oneof a pair of Ticknor pier tables in Dartmouth's collection. It was made in Bostonaround 1820, of mahogany, chestnut, andwhite pine with highly figured mahoganyveneers. Such tables, designed to fill thewall spaces between pairs of windows, werecharacterized by columnar legs, marbletops, and mirrored back panels, and thisone is accented by ormolu caps, bases, anddecorative mounts probably imported fromFrance.

At the beginning of the 19th cen-tury, a mirror was "a circular con-vex glass in a gilt frame," in which,the reflected rays being collected toa point, "the perspective of theroom . . . produces an agreeableeffect." Flat-surfaced mirrors werethen called "looking glasses." Thegirandole mirror here, a magnificent 65 inches high, was made in1810, probably in this country, ofgold leaf and gesso over wood.

At right is the Olcott sideboard,made of mahogany and satinwoodveneers on white pine or spruce.The unusual variety and arrange-ment of its inlays place it firmlywithin the rural cabinetmakingtradition of the Connecticut RiverValley, and it is thought to havebeen made in 180.1 by Julius Barnard, who lived in Hanover duringthat year and corresponded withMills Olcott about making furniture for him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

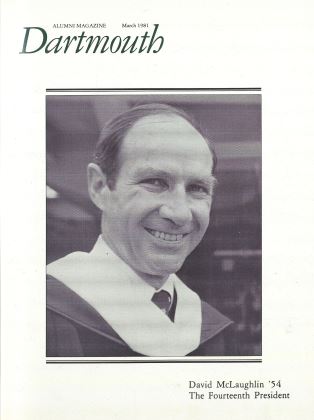

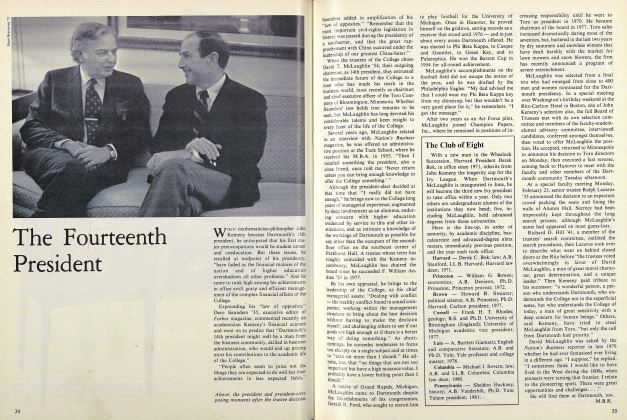

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleImagining Beyond Limits

March 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1981 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1967

March 1981 By CLEMSON N. PAGE, JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

March 1981 By ROBERT D. BLAKE

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

DECEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

DECEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

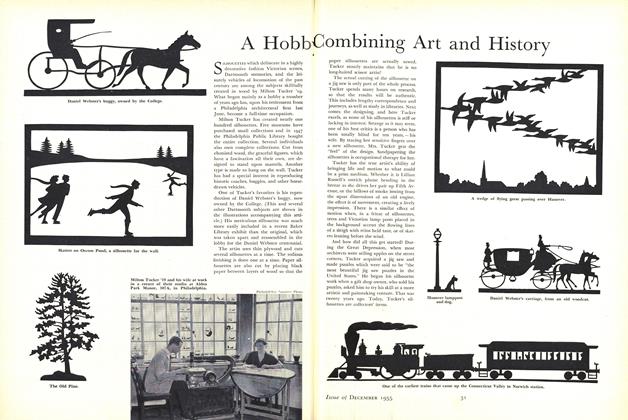

FeatureA Hobby Combining Art and History

December 1955 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPLEA TO ADMIT EDWARD MITCHELL, CLASS OF 1828

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

OCTOBER 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureFishing the Grant with John Dickey

NOVEMBER 1965 By EDWARD WEEKS, LITT.D. '50 -

Feature

Feature"The Record of Their Fame"

December 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

FeatureDiary of a Long Distance Runner

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Tim Hartigan '87