IT is snowing outside, and at the moment the tall, white-haired scholar sitting amid the piled paper, of her office is probably one of the few people in the Upper Valley who has a kind word for Air New England. She says she enjoys the relative inaccessibility, the remoteness it represents. Elise Boulding doesn't need to add that she flies a lot anyway; as a distinguished sociologist and activist, she is on call the world-over.

Boulding, who heads the Sociology Department here, is explaining the whys of her decision to accept a Dartmouth faculty appointment in 1979. (She and her hus- band Kenneth, an eminent economist, had spent much of the previous year here as Montgomery Visiting Professors.) She wanted, she says, to teach at a small college that had displayed a commitment to public affairs, and Dartmouth fit the bill. Her considerable international work, she concluded, could be accomplished as easily from Hanover as from anywhere else in the U.S., and family ties had already influenced her to remain in this country.

The conversation quickly progresses from airlines and Hanover to Tokyo, where Boulding will shortly attend her first meeting as a member of the United Nations University Governing Board, which is roughly equivalent to Dartmouth's Board of Trustees. The U.N. University established by the General Assembly in the early 1970s sponsors research and international conferences on the subjects of natural resources, world hunger, and human and social development. Boulding has long been associated with the U.N.; she presently serves on the U.S. Commission for UNESCO.

Eager to discuss substantive questions, Boulding explains that the importance of the U.N. University programs for her own intellectual growth lay first in impressing upon her the diversity of development models currently circulating among the world's nations. "I had been educated to a completely unreal image of the world community: that all the rest of the world was backward and it was all going to become Westernized and then we'd all sort of go forward. And that's not what's happening at all. As the other [cultural] traditions begin to formulate their development models and pick and choose what they want from the West, the 21st century is going to look different from anything any of us can imagine."

The last phrase is coincidentally ironic: Boulding is a well-known advocate of the imagination and its ability to provide alternatives to unpalatable but seemingly necessary choices, says Dana Meadows, the friend who first persuaded her to teach at Dartmouth for the 1975 summer term. Boulding's interest in the imagination stems from her first major publishing effort, the translation from the original Dutch of futurologist Fred Polak's two volume study, Image of the Future. Polak's notion of "imaging the future," or conceiving of options not present in the current environment, struck a sympathetic chord in Boulding. Meadows, associate professor of environmental studies, explains that her friend, motivated by Quaker pacifism, had been looking for a way of engendering in her children the ability to find non-violent solutions to disagreements. In Polak, Boulding found a theoretical answer that blended her early work in the sociology of the family with an interest in the then inchoate academic field of peace and conflict-resolution.

A pioneer in the sphere of peace studies, Boulding was named, in January 1980, as one of three members of a congressional committee on Proposals for the National Academy of Peace and Conflict Resolu- tion. The committee is charged with in- vestigating and documenting the feasibility of establishing such an academy and is now in the process of writing its final report. Says Boulding, "There is a desperate need for training in the skills of conflictresolution and the analysis of conflict in such a way that you can de-escalate it rather than escalate it. We're very good at escalating conflict and very poor at deescalating it." She contends that the military has supported the concept of a peace academy. Military officials, she relates, say, "We're being brought in where we shouldn't be. Our business is to be the last resort when all other means have broken down, but nobody's working on the other means." Boulding, admittedly "a hopeless optimist," also admits that it will take some time to convince Congress and the new administration of the urgency of this need.

Boulding the scholar, who supplements Boulding the anti-war activist, feels that the United States needs a more inclusive and far-sighted definition of national security, one not characterized by the pre- sent "excessive preoccupation with nationalism per se, with being number one,"but "with the security and welfare of our society over the long run." She sees environmental damage as a serious threat to our security, and hence has become involved in a series of panels, sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, on potential climatic disturbances induced by carbon dioxide pollution.

The subject of atmospheric perils seems fairly far afield for a sociologist whose primary work has been done with the family, women, and the resolution of con- flict, but Boulding considers environmental issues and society's ability to handle them as much a matter of security as short-run concerns about weaponry equivalency. "Our security," she affirms, "lies in knowledge and the application of knowledge, in the skills of mediation and resource distribution. I see the climate project as a way of getting us into a more problem-solving mode."

In her work with society's manifold problems, Boulding steps outside the conventional limits on the academic. Says associate dean of the faculty Donald McNemar, "Her thought and scholarship will not be bound by ordinary disciplinary boundaries." Dana Meadows adds "Everything about her is consistent and absolutely purposeful, and everything that's happened to her she's used to gain a more complete view of [the world]. Her diversity is something that cannot be summed up."

Boulding's past does provide her with a rich collection of experiences on which to draw. The wife of an academic, she decided to lay aside her own scholarly ambitions when her children she has five started to arrive. "I was working on a master's degree when our first child was born and I did continue studying for a couple of years afterwards, but it just became a little too complicated. By the time our third was born I realized that I couldn't do it all. My frame of mind was, 'This is a stage in my life and this will have everything of me during these years. The children will be older later and then other choices will be open to me.' That's a very traditional attitude and I don't think many young people today would do it that way, but I had been socialized to be able to think that way. And I enjoyed every minute of it."

Boulding did manage to produce some research during those years, thanks to her fellow mothers in the Ann Arbor, Michigan, Friends Meeting, who took turns caring for one another's children. Quaker activities are a constant in Boulding's life: She participates in the Hanover Meeting and has written a number of articles and pamphlets relating to her religious thinking. Meadows describes her as a deeply spiritual person who has integrated belief and deed. But beyond the social aspects of her personal theology, Boulding values the solitude and introspection that are an essential part of her religious life. (From one religious retreat came her cookbook, From aMonastery Kitchen.) "Helping everyone and being sensitive to one's own needs for quiet, for times of retirement and reflection is very important," she suggests. "Without being centered and having quiet times there's just no way I could function."

Perhaps Boulding's most outstanding academic achievement is her study TheUnderside of History: A View of WomenThrough Time. In it, she traces women's activities over the centuries with the aim of discovering how society operates beyond the kings and wars and revolutions. According to Meadows, Boulding argues that much of the burden of society is carried by women but that their contribution to what is commonly regarded as history is often overlooked. Says Boulding, "I'm always looking for ways to document what is socially invisible. What is visible in our society is, to put it very crudely, what white men between the ages of 25 and 60 think. But what's happening in society is what everybody is doing, from the ages of two, three, four until they die."

Her work on broad social processes has not, however, blinded Boulding to the relevance of individual experience. Because she sees the family as a microcosm of the world,, she uses her personal and scholarly knowledge of the family's workings to balance her extended research. "It's no use knowing something at the global level if you don't understand how it connects with people locally," she says. One instance of this principle at work is her current research project with a team of social scientists at the University of Colorado's Institute of Behavioral Science. (Boulding was a project director of the institute while on the Colorado faculty). The all-woman team a demographer, a geographer, an economist, and a sociologist has just published its initial study on women in boomtowns.

What they found in the case of two Colorado towns was that economic upsurge brings with it an array of punishing effects; violence, crime, drug use, divorce, alcoholism rates all rise. The study-inprogress, involving door-to-door surveys by Boulding, will attempt to "look underneath the surface disorder and see how people are coping, what the conditions are under which they can actually begin constructing a more human environment for themselves. We're looking at it with the particular policy interest of helping planners see how they can relate to the strengths of a community without bringing in outside professionals who may erase all local capabilities and capacities and maybe do things that are irrelevant, that ignore some of the good things that are already happening."

The lesson is well learned in Hanover. In just a short while, Boulding has become one of the faculty most involved in issues of College life and policy. Having served on the Committee on the Quality of Student Life, she is articulate about the pressing lack of campus social facilities and the relative merits of the Dartmouth Plan, which she considers an asset particularly because of its off-campus learning opportunities. She also advises the Gay Students Association, has conducted a survey on the fears in the College community in general and among women in particular, has arranged lunches and seminars for women faculty, and is organizing an informal curriculum and advising staff for students interested in peace and conflict-resolution studies all in addition to the normal teaching load, administration of the Sociology Department, an active role in the local community, research, and her many outside commitments.

"There are a lot of caring people," she says of Dartmouth. Clearly, she is one of those attempting to make this a better place. "My husband always says that 'everything you do to help people hurts them, and everything you do to hurt people helps them.' What that means is we have very little understanding yet of social process. What's appropriate there is humility. But it doesn't make me despair of studying social process. I'm continually trying to understand under what circumstances we make things better for each other. Because sometimes we do."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

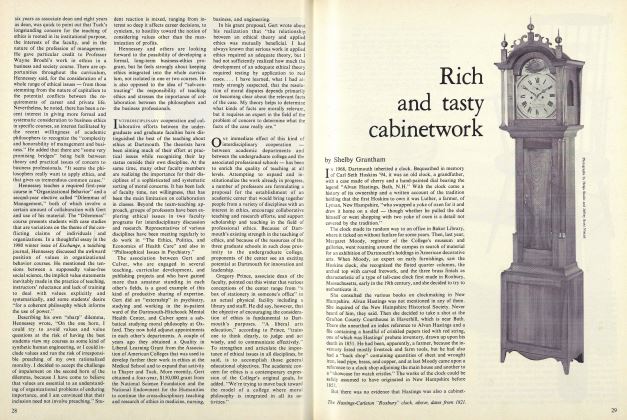

FeatureRich and tasty cabinetwork

March 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

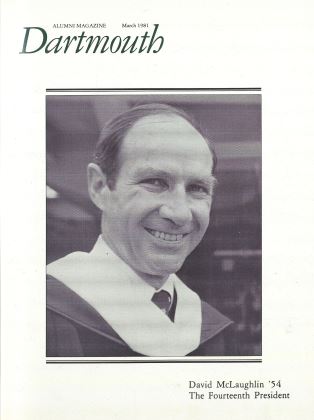

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1981 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1967

March 1981 By CLEMSON N. PAGE, JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

March 1981 By ROBERT D. BLAKE

Don Rosenthal '81

-

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleA Little Medicine

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleBeware the Shrimp

Jan/Feb 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleWhere They Live

April 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleMind for Adventure

May 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleA Straight Talk

June 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81