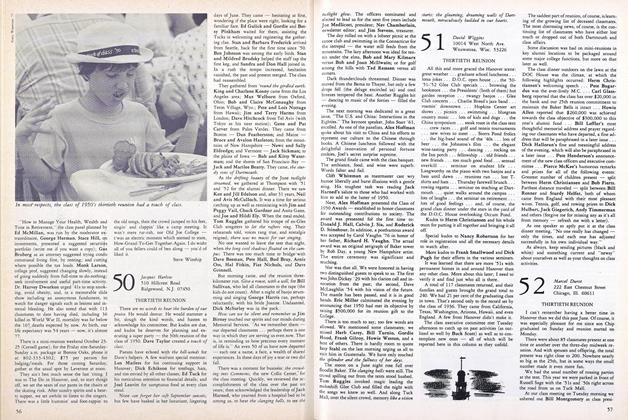

AT THE beginning of spring term seniors vote to select a "professor of the year," marking three choices. One student told me she had no hesitation. Her choices, in order: Mary Kelley, Mary Kelley, Mary Kelley.

Assistant professor of American intellectual and cultural history, Kelley has attracted an enthusiastic following. The first class she offered here in 1977 drew seven students. ("None had registered before the lectures began.") Now, course size has swelled to 80, forcing a move from Reed Hall to Hopkins Center. Her courses American Intellectual History through and since the Civil War demand the work the word "intellectual" in the title implies: Kelley inspires and challenges.

"What I want to talk about today," she begins, clearly outlining the topic as she stands behind the podium, and then proceeds to discuss the conflicting views of Bourne and Dewey on World War I. She remembers trying to conceal shaking hands and knees the first time she taught. But she recalls, too, "I liked it. I felt very natural at it." Now she speaks with measured calm, delivering her well-prepared talk like carefully edited prose already in print. Her hands gesture discreetly to emphasize points; her voice is melodious. If teaching seems natural to her, Kelley admits, "You have to work at it all the time." She brings American history not the battles and wars but the debates and attitudes to life, touching on issues like Puritanism, Enlightenment, and pacifism.

Seeking to avoid what she calls "pitchercup" learning in which the professor pours knowledge into cups and the "cups are dumped onto the examination booklets," she strives to make learning a dialogue. "My task as a teacher is not simply to dispense knowledge to you," she told incoming freshmen last year. "In the classroom we will together attempt to research and interpret the history of the United States. We will try to discover the nature of America's past and to understand how that past merges with the present." She encourages questions, learning as many students' names as possible to make the exchanges real.

Teaching does not stop at the end of the period. She waits class to straighten puzzled brows. Students find her ap- proachable and fair. She advises them on papers, research projects, theses, and ma- jors, taking time to criticize, to probe, and to laugh. "The classroom is only the tip of the iceberg," explains Kelley. Hours are spent preparing for lectures. She sifts through primary sources, reconstructing and analyzing American history to find threads to draw throughout her courses and to find quotations to illuminate the perspectives of the period.

Some challenge her approach to history, maintaining that she is teaching philosophy chronologically. "No," she counters. "The ideas are important in shaping peoples' perceptions of reality." When she explores the religious movements of early American history, for example, she places the perceptions in a historical context, pointing to "the reciprocal relationship of the environment and the idea."

To Kelley, history is broad by definition. It is a splendid, multi-colored, rich tapestry," she says. "By examining the tapestry, the threads and how they are woven together, we can understand what we are today." In her own research Kelley examines the history of American women, "enlarging the tapestry and finding out more about women's pasts" finding, too, the exploration of previously "uncharted territory" exciting. When she first mentioned Charlotte Perkins Gilman, an early 20th-century feminist, in class, one student asked, "Why are you doing this?" Today, Kelley finds increased awareness. She cautions students to test generalizations to find out if they are universally true, asking "When they say men, are they using the term generically to mean all of humanity or do they mean men?" She notes language can be prescriptive as well as descriptive. "If we want as full an understanding of history as possible, we have to examine all of humanity."

Just as new material can be integrated into the classroom, new courses are being integrated into the curriculum through the Women's Studies Program. On the program steering committee, Kelley is one of a team teaching the introductory course and '"Women's Work and Culture in Industrializing Societies," a new course this fall. One issue the program considers is feminism, but Kelley tells her students, "There is no such thing as feminism. There are feminisms, a wide variety of perspectives." She pauses. "In the end the issue is human equality. In that context everyone defines themself as a feminist." She laughs, admitting that she has worked on this definition for some time.

Whether she is teaching women's studies, history, or summer courses for corporate executives, public servants, and nonacademic professionals at the Dartmouth Institute as she did last term Kelley's humor and enthusiasm seldom flag. She draws her energy from her research, she says. "Most institutions make a choice between teaching and scholarship," she says, "while Dartmouth tries to do both." It's a commitment she finds as exciting as it is demanding.

Having published two years ago an anthology entitled "Women's Being,Woman's Place: Female Identity and Vocation in American History, Kelley has almost completed work on a book about a dozen 19th-century women writers among them Harriet Beecher Stowe. She has examined their fiction and their personal papers letters, diaries, and journals to explore the contradictions and tensions within their roles as homemakers and writers. "They could not fully define themselves as writers," she has found. "They saw two worlds: women in the private sphere and men in the public sphere."

Kelley's commitment to a career as a writer and teacher was encouraged from the first by her husband, novelist Robert Kelley '61. "Robert is simultaneously my most supportive and most stringent critic," she notes. The Kelleys' lifestyles blend together in a rich harmony of shared enthusiasms and concerns. If her marriage has been a supportive and stimulating partnership helping her in her career, Kelley recognizes some of the obstacles other women faculty may face - raising children or living apart from spouses who work elsewhere.

Kelley s profession takes her beyond the boundaries of the College. She has lectured in many places throughout the nation and served as a consultant for the National Endowment for the Humanities. Among other extra-curricular responsibilities at Dartmouth, she was one of six faculty members who advised the search committee that recommended President McLaughlin to the trustees.

She sees two major objectives ahead for the College: increasing heterogeneity and deeper emphasis on the intellectual environment. "We should encourage as much heterogeneity as possible so that the College reflects the diversity and richness of the culture from which we come." Kelley finds this consistent with the educational purpose of the institution "we should not be educating men and women but humanity." With diversity comes the dialogue she treasures in and beyond the classroom, a dialogue that favors analysis and critical thinking over stereotyping, that encourages intellectual exchange.

Dartmouth needs to emphasize this intellectual environment, she believes, to make the implicit more explicit. In an address to the freshman class she described a community at Dartmouth "the community of intellectuals dedicated to the life of the mind" and invited freshmen to join. "Above all, if you leave here with the intense conviction that the life of the mind is crucial to any life worth living, then you will leave here as a permanent member of the Dartmouth intellectual community." She dismisses the separation between thinking and acting thinking in the "unreal" world of college and acting in the "real" world after Dartmouth. "Do not think that you are here to prepare for life, because your life is now."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

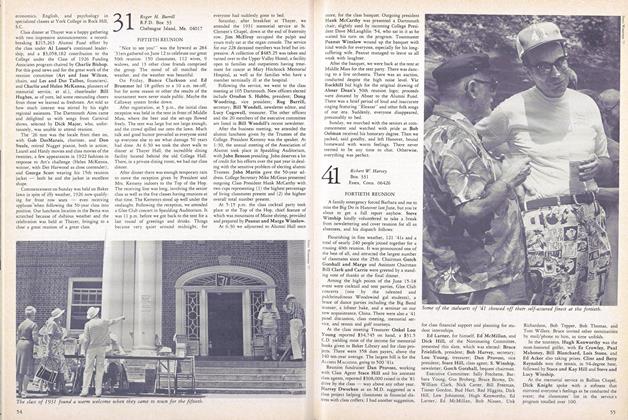

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

September 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryInauguration of the 14th President: The Spirit of Eleazar Wheelock ... Transmitted through his Successors'

September 1981 -

Feature

FeatureAll the Presidents's People

September 1981 By J. N. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

September 1981 By Clement B. Malin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

September 1981 By Jacques Harlow -

Sports

SportsMany Are Called

September 1981 By Brad Hills '65

Beth Ann Baron '80

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE NEW GYMNASIUM IN OPERATION

May, 1911 -

Article

ArticleTHE TRUSTEES' MEETING

April, 1915 -

Article

ArticleOBERAMMERGAU OF THE PASSION PLAY

May 1934 -

Article

ArticleHopkins Center

December 1946 -

Article

ArticleTrustees endorse $2-million divestiture

MAY 1985 -

Article

Article"Kiki" McCanna: Steward of Sanborn

APRIL 1986 By Lee McDavid