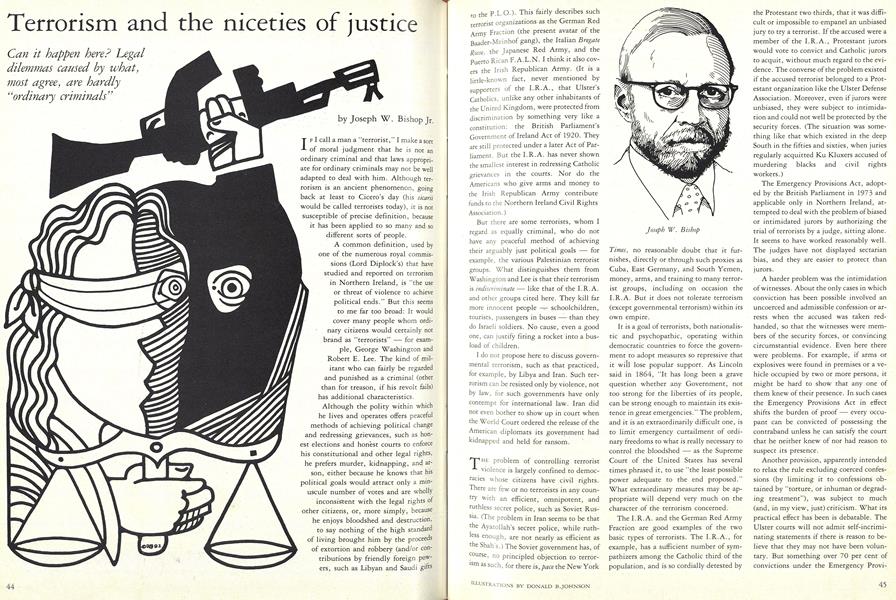

If I call a man a "terrorist," I make a sort of moral judgment that he is not an ordinary criminal and that laws appropriate for ordinary criminals may not be well adapted to deal with him. Although terrorism is an ancient phenomenon, going back at least to Cicero's day (his sicarii would be called terrorists today), it is not susceptible of precise definition, because it has been applied to so many and so different sorts of people.

A common definition, used by one of the numerous royal, commissions (Lord Diplock's) that have studied and reported on terrorism in Northern Ireland, is "the use or threat of violence to achieve political ends." But this seems to me far too broad: It would cover many people whom ordinary citizens would certainly not brand as "terrorists" for example, George Washington and Robert E. Lee. The kind of militant who can fairly be regarded and punished as a criminal (other than for treason, if his revolt fails) has additional characteristics.

Although the polity within which he lives and operates offers peaceful methods of achieving political change and redressing grievances, such as honest elections and honest courts to enforce his constitutional and other legal rights, he prefers murder, kidnapping, and arson, either because he knows that his political goals would attract only a minuscule number of votes and are wholly inconsistent with the legal rights of other citizens, or, more simply, because he enjoys bloodshed and destruction, to say nothing of the high standard of living brought him by the proceeds of extortion and robbery (and/or contributions by friendly foreign powers, such as Libyan and Saudi gifts to the P.L.0.). This fairly describes such terrorist organizations as the German Red Army Fraction (the present avatar of the Baader-Meinhof gang), the Italian BregateRosse. the Japanese Red Army, and the Puerto Rican F.A.L.N. I think it also covers the Irish Republican Army. (It is a little-known fact, never mentioned by supporters of the I.R.A., that Ulster's Catholics, unlike any other inhabitants of the United Kingdom, were protected from discrimination by something very like a constitution: the British Parliament's Government of Ireland Act of 1920. They are still protected under a later Act of Parliament. But the I.R.A. has never shown the smallest interest in redressing Catholic grievances in the courts. Nor do the Americans who give arms and money to the Irish Republican Army contribute funds to the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association.)

But there are some terrorists, whom I regard as equally criminal, who do not have any peaceful method of achieving their arguably just political goals ― for example, the various Palestinian terrorist groups. What distinguishes them from Washington and Lee is that their terrorism is indiscriminate ― like that of the I.R.A. and other groups cited here. They kill far more innocent people ― schoolchildren, tourists, passengers in buses ― than they do Israeli soldiers. No cause, even a good one, can justify firing a rocket into a busload of children.

I do not propose here to discuss governmental terrorism, such as that practiced, for example, by Libya and Iran. Such terrorism can be resisted only by violence, not by law, for such governments have only contempt for international law. Iran did not even bother to show up in court when the World Court ordered the release of the American diplomats its government had kidnapped and held for ransom.

THE problem of controlling terrorist violence is largely confined to democracies whose citizens have civil rights. There are few or no terrorists in any country with an efficient, omnipotent, and ruthless secret police, such as Soviet Russia. (The problem in Iran seems to be that the Ayatollah's secret police, while ruthless enough, are not nearly as efficient as the Shah's.) The Soviet government has, of course, no principled objection to terrorism as such, for there is, pace the New York Times, no reasonable doubt that it furnishes, directly or through such proxies as Cuba, East Germany, and South Yemen, money, arms, and training to many terrorist groups, including on occasion the I.R.A. But it does not tolerate terrorism (except governmental terrorism) within its own empire.

It is a goal of terrorists, both nationalistic and psychopathic, operating within democratic countries to force the government to adopt measures so repressive that it will lose popular support. As Lincoln said in 1864, "It has long been a grave question whether any Government, not too strong for the liberties of its people, can be strong enough to maintain its existence in great emergencies." The problem, and it is an extraordinarily difficult one, is to limit emergency curtailment of ordinary freedoms to what is really necessary to control the bloodshed as the Supreme Court of the United States has several times phrased it, to use "the least possible power adequate to the end proposed." What extraordinary measures may be appropriate will depend very much on the character of the terrorism concerned.

The I.R.A. and the German Red Army Fraction are good examples of the two basic types of terrorists. The I.R.A., for example, has a sufficient number of sym- pathizers among the Catholic third of the population, and is so cordially detested by the Protestant two thirds, that it was difficult or impossible to empanel an unbiased jury to try a terrorist. If the accused were a member of the I.R.A., Protestant jurors would vote to convict and Catholic jurors to acquit, without much regard to the evidence. The converse of the problem existed if the accused terrorist belonged to a Protestant organization like the Ulster Defense Association. Moreover, even if jurors were unbiased, they were subject to intimidation and could not well be protected by the security forces. (The situation was something like that which existed in the deep South in the fifties and sixties, when juries regularly acquitted Ku Kluxers accused of murdering blacks and civil rights workers.)

The Emergency Provisions Act, adopted by the British Parliament in 1973 and applicable only in Northern Ireland, attempted to deal with the problem of biased or intimidated jurors by authorizing the trial of terrorists by a judge, sitting alone. It seems to have worked reasonably well. The judges have not displayed sectarian bias, and they are easier to protect than jurors.

A harder problem was the intimidation of witnesses. About the only cases in which conviction has been possible involved an uncoerced and admissible confession or arrests when the accused was taken redhanded, so that the witnesses were members of the security forces, or convincing circumstantial evidence. Even here there were problems. For example, if arms or explosives were found in premises or a vehicle occupied by two or more persons, it might be hard to show that any one of them knew of their presence. In such cases the Emergency Provisions Act in effect shifts the burden of proof every occupant can be convicted of possessing the contraband unless he can satisfy the court that he neither knew of nor had reason to suspect its presence.

Another provision, apparently intended to relax the rule excluding coerced confessions (by limiting it to confessions obtained by "torture, or inhuman or degrading treatment"), was subject to much (and, in my view, just) criticism. What its practical effect has been is debatable. The Ulster courts will not admit self-incrimi-nating statements if there is reason to believe that they may not have been voluntary. But something over 70 per cent of convictions under the Emergency Provisions Act are based wholly or partly on admissions to the police, and there have been many complaints by accused terrorists, both Catholic and Protestant, of police brutality. None has been substantiated, but some are probably true. (The problem, as pointed out by an able and impartial observer, is that the complainants are exactly the sort of people the security forces would be tempted to mistreat, and also exactly the sort of people who would claim they had been mistreated even if they had not been.) Likewise the Emergency Act expands the security forces' powers of arrest, permits detention for a period up to 48 hours (or seven days under another emergency statute), and search and seizure without warrant.

The purpose and effect of these and other, less drastic, provisions of the British legislation was to facilitate prosecution and conviction by something like the usual criminal process, thereby eliminating the need for internment, which meant locking suspects up for an indefinite period, without either charges or trial. The convict population has approximately quadrupled since the passage of the Emergency Act and the number of bombings and shootings has declined by about a third. The government felt able to end internment at the end of 1975.

THE problem was very different, and different emergency legislation was enacted, in the Federal Republic of Germany. The principal similarity between West Germany and England was that in each the legislature made membership in a violent organization an offense, to facilitate conviction of those who planned acts of terror but did not themselves carry them out. In Germany, there was virtually no bias in favor of the terrorists in the general population. It has been estimated that the left-wing terrorists, who number only about 20 or 30 hard-core killers, have not more than a thousand reliable supporters — although the recent increase in leftradicalism ― among German youth, especially university students, may mean that there are more potential recruits and more aiders and abettors.

Perhaps the most difficult problem, which seems not to exist in Northern Ireland, was presented by the radical lawyers who represented accused terrorists. They regularly attempted to turn the trials into forums for radical propaganda and otherwise to disrupt them ― conduct which an American court could have punished as contempt. But German judges had no inherent power to punish contempt; all they could do was temporarily remove from the courtroom lawyers and spectators who engaged in such conduct. Moreover, some of the defense counsel abused their privilege of conferring privately with their clients, not merely by acting as couriers between captured terrorists and those still at large, but by smuggling into the prison such contraband as weapons, explosives, and radios. These deficiencies were remedied by emergency legislation, notably the Sperrkontaktgesetz, which empowers a judge to prohibit physical contact between the lawyer and his client.

The police were given expanded powers of search and seizure. For example, if the police have reason to believe that a suspect is concealed somewhere in a large apartment complex, but do not know in which apartment, they can be authorized to search all the apartments and for a limited period to stop and examine all persons leaving the area. So far, these measures seem to have been reasonably effective. The only serious terrorist outrages in the last two or three years were the planting (by a member of a neo-Nazi organization) at the 1980 Munich Oktoberfest of a bomb which killed 13 people, happily including the terrorist himself, and the bombing by left-wing extremists of an American military installation in which several people were killed. Although there was no evidence that the leaders of the neo-Nazi group had ordered or been privy to the planting of the bomb at the Oktoberfest, it was declared an illegal organization, membership in which could be prosecuted as a crime.

In neither Northern Ireland nor Germany, nor in Italy or Israel, is the death penalty authorized for murder, no matter what the murder's motivation. In my opinion, this is a mistake in the case of terrorist murderers, for several reasons: Imprisonment is a less effective deterrent for terrorists, many of whom (like the I.R.A.) are convinced that they will be released when their cause triumphs; an imprisoned terrorist is simply an invitation to his friends to force his release by raiding the jail, kidnapping hostages, or hijacking airplanes. Against the argument that hanging a terrorist murderer strengthens his cause by making him a "martyr," it may be pointed out that he is also a "martyr" as long as he stays in prison and that, if he be sufficiently fanatical, he can turn himself into a dead martyr by a hunger strike (as in the case of the I.R.A. zealots) or by other methods of suicide (as in the case of some of the German terrorists).

In my view, one of the strongest defenses against terrorist extortion, when hostages are kidnapped or airplanes hijacked, is a strong, consistent policy of never bargaining with the terrorists, except in order to persuade them to surrender or to gain time to mount a military strike. Israel has steadfastly maintained such a policy, and so has the .Federal Republic of Germany afer a shaky start at the Munich Olympics in 1972. The United States has not been firm or consistent. Governments like Libya, North Korea, and Vietnam cannot have failed to conclude from the Carter administration's irresolute, vacillating handling of the Iranian crisis that the way to. extract concessions from the United States is to kidnap its diplomats and hold them for ransom. Unless and until the present administration demonstrates a determination like that of Israel and West Germany, diplomatic relations with such lawless governments as Iran or Vietnam seem to me highly inadvisable. Civilized behavior is wasted on the likes of the Ayatollah Khomeini or Colonel Quadaffi

WE do not have in the United States today terrorist violence like that in Ulster or Germany or Italy. The F.A.L.N., the terrorist branch of the Puerto Rican independence movement, has destroyed life and property out of all proportion to its minuscule membership, but it has so far been adequately controlled by normal criminal procedures. The Weather Underground and the Black Liberation Army have recently demonstrated that, although they have been chased down ratholes, they are not dead. But they are so much less skilled than their foreign counterparts, and have so few supporters among the citizenry and the legal profession (except for the likes of William Kunstler), that no extraordinary measures have thus far been needed to control them.

We are, however, certainly not immune to the terrorist plague. Suppose there were in this country violence like that in Northern Ireland, not controllable by the ordinary process of law enforcement, would the courts and the Supreme Court allow Congress and the President to do some or all of the things the British government has done? Juryless trials? Making mere membership in organizations committed to violence itself a crime? Shifting the bur- den of proof to the accused in certain cases? Internment? Three years ago I participated in a conference in England on terrorism. Eminent British judges and lawyers who were there all thought such things would be impossible under the Constitution of the United States. This was because they had read the First, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments but not the decisions of the Supreme Court applying those amendments to the actions of Congress and the President in great emergencies.

Some of those decisions are difficult or impossible to reconcile with others. Thus, in Ex parte Milligan, decided in 1866, the Supreme Court held that neither Congress nor the President could in any circum- stances authorize the trial of civilians by military tribunals so long as the civilian courts were "open." But in 1942, the Court, implausibly distinguishing the Milligan case, held in Ex parte Quirin that the President, acting under a provision of the former Articles of War (an Act of Congress), could constitutionally order the trial of eight Nazi saboteurs, all civilians and one an American citizen, by a military commission - although the civilian courts were, of course, open and functioning. In 1946, however, the Supreme Court, relying on Milligan, held in Duncan v. Kahanamoku that the state of martial law that was declared in Hawaii after Pearl Harbor could not justify the trial of two civilians by military courts. (Technically, the decision held that the "martial law" authorized by the Hawaiian Organic Act was not intended to authorize such trials, but the Court's language made it plain that if the act had explicitly permitted military trials, it would have been held unconstitutional.)

The Fifth Amendment's provision that no one shall be deprived of liberty without due process of law would seem to forbid internment, locking people up indefinite ly without any sort of trial or even charges. But in 1909, Justice Holmes, in Moyer v. Peabody, upheld the power of a state governor to confine, without charges or trial, a labor leader whom the governor thought likely to add to the violence of a violent labor dispute. And in Korematsu v. UnitedStates (1944), the Supreme Court held that, pursuant to an Executive Order of President Roosevelt (which had been quickly ratified by an Act of Congress), American citizens could constitutionally be deported from their homes on the West Coast and confined in "relocation centers," without being convicted of or even charged with any sort of wrongdoing, for no other reason than that their ancestors had been Japanese. (Even in the Milligan and Duncan cases the Court conceded that the military could "arrest and detain civilians . . . at a time of turbulence and danger from insurrection or war." If the military authorities can do such things, it is hard to see why civilian officials could not.)

These apparent contradictions can be explained if one notices that the principal cases upholding military trials and internment were decided during the great national emergency of war, the others after the war was over. The whole pattern of the Supreme Court's opinions on the curtailment of civil liberties in time of war shows that the justices will be very slow to interfere with the discretion of the executive and legislative branches in dealing with what the Court perceives as a great emergency. (If there is no substantial support for the authorities' belief that there is any serious emergency, the judges will not tolerate curtailment of civil freedoms.)

Another example: The Constitution provides that "the Writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the Public Safety may require it." It has generally been thought, although the issue has never been decided, that only Congress can suspend the Writ. But Lincoln suspended it unilaterally at the outbreak of the Civil War, and Roosevelt suspended it in the case of the Nazi saboteurs, without either Congressional sanction or the existence of either invasion or rebellion. In each case the Supreme Court managed to avoid deciding whether the suspension was constitutional.

THE rule that I believe the Supreme Court would apply if the United States were faced with a situation like that in Ulster, or any sort of serious violence which could not be controlled by the ordinary criminal process, and if Congress and the President were to resort to some or all of the measures adopted by the British Government, was best stated in two decisions of the court, 80 years apart. Mitchell v. Harmony (1852) involved the legality of the military authorities' seizure of a citizen's property during the Mexican War. Chiefjustice Taney said, "Every case must depend on its own circumstances. It is the emergency that gives the right, and the emergency must be shown to exist before the taking can be justified. (The Court went on to find that there was no emergen cy sufficient to justify Colonel Mitchell's seizure of Mr. Harmony's mules.) Eighty years later, [a. Sterling v. Constantin (1932), the Supreme Court invalidated a state governor's declaration of "martial law," pursuant to which he had ordered the state militia to block enforcement of a federal court's order, because it found that there was in fact no emergency requiring any such drastic action. Chief Justice Hughes quoted Taney's language and added, "What are the allowable limits of military discretion, and whether or not they have been overstepped in a particular case, are judicial questions." These principles seem applicable to both state and federal gov ernments and to civilian as well as military authorities.

In short, applying these tests, if the Court found that there was in fact a serious emergency,, and that the means employed to control the violence were "the least possible power adequate to the end proposed," it would hold constitutional every measure the British have taken in Ulster and possibly even more drastic steps Moreover, if history is a guide, it would give the government the benefit of the doubt, so long as the emergency lasted.

Can it happen here? Legaldilemmas caused by what,most agree, are hardly"ordinary criminals''

Joseph W. Bishop

Joseph Bishop '36 is Richard Ely Professor ofLaw at the Yale Law School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat keeps them going? A 'Mystic Glue' Perhaps

May 1982 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Feature

FeatureImpacts simply positive

May 1982 -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

May 1982 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1964

May 1982 By Alexander D. Varkas Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

May 1982 By John L. Gillespie -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

May 1982

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Hopkins Center Concept

April 1956 -

Feature

FeatureThe Medical School

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

FEBRUARY 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Cover Story

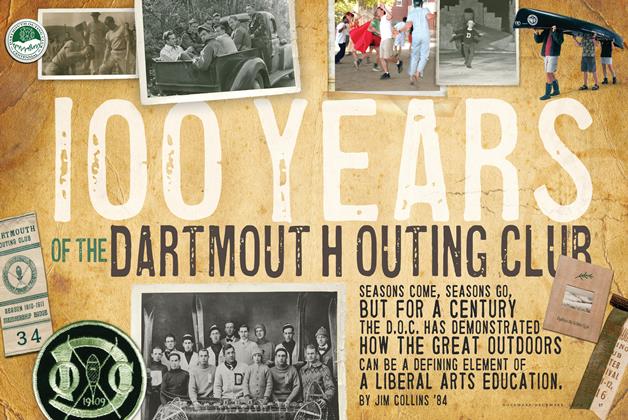

Cover Story100 Years of the Dartmouth Outing Club

Nov/Dec 2009 By Jim Collins ’84 -

Feature

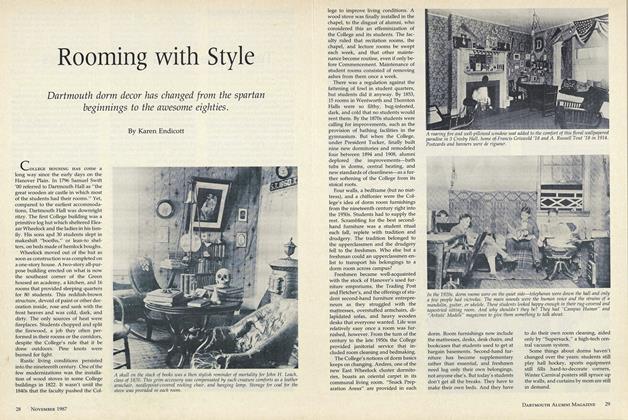

FeatureRooming with Style

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

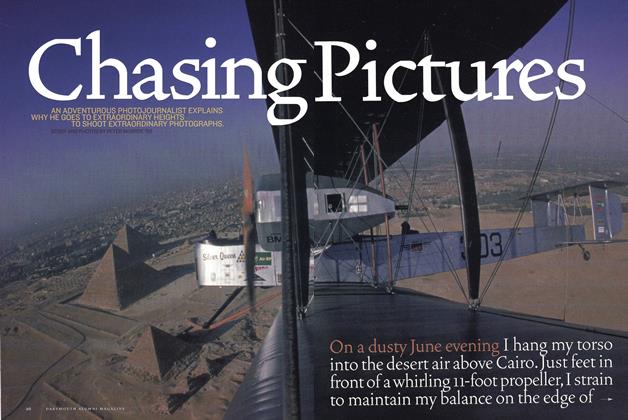

Cover StoryChasing Pictures

Jan/Feb 2002 By PETER McBRIDE ’93