IIepì Tŵv Néwv IIayaiŵv

De Antiquitatibus Novis

SEVERAL years back (before he became the embattled owner of the Atlanta Braves and defender of the America's Cup) billboard scion Ted Turner, then a classics major at Brown, received a letter from his dad. "My dear son," he read, "I am appalled, even horrified, that you have adopted classics as a major. As a matter of fact, I almost puked on the way home today."

It's a reaction many a young student of the classics has had to face from many a dad working his tail off to pay the bursar. "Useless!" they shout at their children. "You'll be a freak and a snob!"

"I know, I know," says Jim Tatum, one of Dartmouth's professors of classics. "People think we're like that funny Pogo character who talks in Gothic script. Sometimes at a party someone will ask me what I do. I say I teach classics, and the person says, 'Oh yeah? You mean like Moby Dick and Shakespeare?' And I say, no, Greek and Latin. Then there's a silence and finally the person asks, 'Why do you want to teach something so esoteric?' "

Time was, when you knew how to read, you knew what was meant by "the classics." Time was. But classics has come a long, long way, baby, since its heyday as the king of the curriculum, and all those angry dads are beating a dead horse. Well, not really dead, perhaps, but thoroughly chastened. No one is more aware than modern classicists of the dangers of both arrogance and irrelevance to a discipline which attracts as few students as theirs has for the past 50 years. The number of classics majors graduated by Dartmouth last year was a five-year high of 11. Compare that to 88 in biology, 97 in English, 111 in history, and a whopping 119 in economics, and it becomes clear that classicists cannot afford to hole up in some lovely ivory tower. Nor are they doing so. "We are facing facts," says Tatum.

Take Geoffrey Kirk, for instance, Regius Professor of Greek at Cambridge and former professor of classics at Yale. "I have sometimes wondered," he writes candidly in a recent essay on the future of classics, "whether classics teachers are more severe and humorless, as well as more complacent, than most others." While he acknowledges the difficulty of retaining perspective in the face of the "grueling task" of becoming adept at Greek and Latin, he makes an impassioned plea to his fellow scholars to take themselves a little less seriously, to be more relaxed about it all in order to make the discipline more attractive. "The most relevant part of Kirk's essay, so far as Dartmouth is concerned," says Tatum, "is the idea that we teachers of classics have more exchange of ideas with our students about what we are doing. The dangers of complacency and even arrogance are real ones, so far as this oldest-of-(academic) professions is concerned."

In descending from the ivory tower into the democratic marketplace of modern higher education, classics is undergoing great changes, is becoming not only more relaxed, but more accessible and more relevant. Or perhaps being more accessible and more relevant equals being relaxed. At any rate, there has been recently a flurry of activity in the field as classicists scurry about revamping their material to suit the age. As Professor Norman Doenges of Dartmouth's classics department explained it back in 1962 in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, the department was adjusting the study of the Greek and Latin languages to "the needs and interests of the present-day student" and broadening its offerings beyond the languages by instituting courses (in translation) in classical literature, history, art, government, and thought as well.

These are significant departures. Traditionally, the study of the classics has been philological — concerned principally with the historical development and the linguistic characteristics of the languages themselves. Kirk explains that the origins of this preoccupation with linguistic problems lie in a very real need that existed between the 17th and 19th centuries for accurate texts. Many ancient Greek and Latin texts were available only in medieval copies, which were frequently defective, and a great deal of textual work was necessary to whip them into shape. But, says Kirk, the traditional skills of recension, emendation, and so on are no longer needed to the great degree they formerly were, since the work of the best authors is currently in good shape. Continuing to emphasize the traditional philological skills in the teaching of classics, he maintains, "involves a degree of wasted energy and sheer repetition and is often accompanied by the insinuation that these are the truly divine skills, with other forms of classical scholarship being inferior."

"It is a suicide path," says Professor Peter Bien, a member of the College's English Department who also teaches modern Greek poetry for the Classics Department. (The department's sponsorship of courses in modern Greek is one evidence, says Bien, of the healthy new attitude: until very recently modern Greek was regarded by classicists as a degenerate language not worth studying.) Tatum agrees that the new approach is essential: "If we continue to have Greek and Latin and transmission of texts our exclusive and solitary concerns, we will cheat everybody. And we have been teaching Latin and Greek in a linguistically unsophisticated and old-fashioned way. A revolution is underway."

IT is difficult to elicit details of the new techniques being used to teach Greek and Latin, but Tatum and others mention skills borrowed from the more up-to-date methods of the teachers of modern languages. The most significant change described by Doenges in 1962 was a reduction of time allotted to elementary study:

The new program is designed... to introduce students as rapidly as possible to the rewarding experience of reading Greek and Latin works as literature. At the elementary level time spent on grammar and drill has been reduced to a minimum. In Greek the general introduction to the language which used to be spread over the greater part of a year is now confined to a single ten-week term. Thanks to new methods the student is ready at the beginning of his second term to read and appreciate Plato. He then goes on, still in the second term, to a play of Euripides, reading which he used not to do until the end of his second year of Greek. The department believes that after three terms of elementary work the student can with concentration and effort read profitably whatever he likes in Greek.

Doenges goes on to explain that the same approach is used in Latin, where "because of these new methods it has been possible to eliminate at the freshman level a full course." Basic to the change, he says, is the unwillingness of the present-day undergraduate to regard the study of language as an end in itself, and he declares that the classics department at Dartmouth has decided that students should not at the undergraduate level be asked or forced so to narrow their interests.

A natural concomitant both of a reduced emphasis on language and literature and of a broadening into other fields is, of course, a greater amount of study done in translation. Majors and non-majors may now choose from a wide selection of courses in translation, the- most popular of which is Greek and Roman Studies I, a survey of great classical works in English translation. ("Take Greek and Roman 1," reads a student course guide. "Take it because you are an English major or a comp lit major. Take it for a humanities distributive. Take it for a gut. Take it for whatever reason, but take it. . . . The reading is great.") This popular course, known locally as "Groms I," is regarded by students and faculty alike as the department's come-on. By attracting large numbers of students (unlike classes in Greek and Latin), it helps the department justify its existence to deans and budgetary committees. ("Personally, I feel that the languages will always be the way into the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome," says Tatum, "but our bread and butter courses are Greek and Roman Studies.")

FEELING is running high in the department about the new classicism. Dartmouth's classicists speak enthusiastically about the benefits of the diversification. Christine Perkell, who was herself trained in the diehard philological manner at Harvard, is quick to point out the joys of literary criticism and interpretation and the excitement of new "idea" courses she hopes to see added to the traditional "author" courses. She is particularly enthusiastic about a course she recently taught on the theme "Love and Death," and she would like to offer one on "The Figure of the Exile."

Archaeologist Jeremy Rutter is free to prefer practical Greek and Latin to the more traditional literary Greek and Latin. He finds that the former is more useful in doing the archaeological research that fascinates him. "I'm a dirt [field] archaeologist," he explains, "rather than an armchair archaeologist. And I teach nuts and bolts Latin, not aesthetic Latin." Rutter's descriptions of the excitement of the "dig" are mesmerizing, and the Dartmouth undergraduates who may get to go with him on excavation in Cyprus will be lucky.

Archaeologist Steven Ostrow draws on his love and knowledge of Roman architecture in teaching language. His Latin I class is studded with magnificent color slides of Roman buildings, which Ostrow links to the class's work by discussing the Latin inscriptions and graffiti they display (some of which would have scandalized the Latin class of yore).

Matthew Wiencke, whose specialty is ancient Greek art and architecture, is particularly interested in the new trend among classicists toward interdisciplinary teaching. He speaks eloquently of the excitement of "going beyond the confines of one's own course" and describes temptingly a course he taught recently in medieval Latin. "Most of the regular class time had to be spent with the language and the translating. But outside the regular time we organized local talent from eight other departments into a medieval colloquium, which we opened to the public. A professor from History lectured on the crusades, someone from Art talked about the Gothic cathedral, we had lectures on medieval music, the Arthurian legends, Charlemagne, all sorts of fascinating discussion."

Stephen Waite's interest in linking computer and classical studies has led him so far from traditional classicism that he now has his office in Kiewit and holds only an adjunct position in his old department, Classics. Waite points with pride to the fact that among humanists, classicists were the first to recover from the non-scientist's automatic abhorrence of The Machine. Since the late forties, classicists all over the western world have been harnessing the computer to their own (largely philological) uses. Waite has been steadily successful in amassing at Dartmouth an archive of classical texts in machine-usable form, and he describes with enthusiasm several of the best classics research projects utilizing computers.

Tatum is excited by the new, sophisticated methods of analyzing ancient myth and ritual. "Classical mythology used to be just an entertaining collection of puerile stories," he says, "but now you teach it at your peril if you don't find out from Anthropology and Psychology and Religion what's going on." Tatum has also collaborated with English and Drama recently in producing onstage his new English translation from the Latin of Plautus' bawdiest play, Casina, an ancient situation comedy which was well received by both town and gown.

THE new classics' teachers and students alike are also anxious to assert the practical benefits of taking classics courses. Greek and Latin are credited with providing valuable exercise in mental discipline, for instance. This benefit, mentioned often enough in the past as a happy by-product, is today regarded as a major justification, especially as the "back to basics" movement gains momentum. Perkell cites it as a timely benefit; "You can't translate without understandsing the complex syntactical Classics is like math that way. There is right and wrong. Such discipline is good, especially in these days of no requirements. Many colleges are afraid to make their programs demanding. Students can go through an entire degree program without ever concentrating. That's too bad for their brains. You have to practice with your brain, do mental gymnastics to keep it in shape."

"The classical languages are more difficult than others, and more logical," says classics honors major Hugh Dyar '78. "Studying them trains the mind well by requiring a daily discipline of work." And Ostrow's Latin I students, in an anonymous course evaluation, praised the course for giving them experience in hard work. "This course has prepared me for rigorous work," wrote one student, "and study habits necessitated by the course will help me in work I'll be facing through both college and life." "The course was quite helpful as an exercise in mental discipline and logical analysis," said another, and others agreed.

But by far the most frequently perceived and confidently offered benefit of classical study derives from the pursuit of Latin in particular: "A more immediate satisfaction with Latin," explains Ostrow, "is that it is an excellent discipline for the unravelling of English grammar." Those same Latin I students bear him out: "I was able to gain great insight into English grammar and structure by learning the pattern of Latin sentences and the explicit functions of each word within sentences," wrote one, and most of the others agreed that they saw "many ways in which Latin will help with English." (Greek student Ann Boyce '81 puts her finger on what may be an important factor in this connection between learning Latin and learning English grammar: "In high school my English grammar was helped a lot by studying Latin. Not that my English teacher taught me any grammar - he didn't, but my Latin teacher taught me Latin grammar, and I compared it to English.")

A question naturally arises in such discussions of the practicality of classical study: Are the values claimed for classics — such as mental discipline and improved skill at English — to be gained only, or even best, from studying Greek and Latin? It is difficult to maintain that the classics, among all the academic disciplines available to the modern student, have a corner on the market in mental discipline. And as to Latin's effect on skill at English, the data conflict. When Doenges was asked whether any other language with some historical connection with English — French, say — would not have the same effect as Latin, he replied, "Yes, it would. But studies were done which show that a combination of Latin and English, as compared to English and language X or to English and support [remedial] English, tends to improve English more and more rapidly." But when pressed to explain what specific characteristics of Latin were involved, he shook his head. "Lord knows why," he said. And Cynthia Bognolo, Hanover High School's successful Latin teacher, recalls a Princeton study showing from CEEB tests that the highest correlation between foreign language study and skill at English is between Hebrew and English, and that Latin and German tie for second place.

(The whole question of the absence of Hebrew from "classical" studies is an intriguing one. Only Dean of Humanities and Professor of Religion Fred Berthold Jr. spoke of it as one of the classics, and only Peter Bien hazarded a guess as to why it is so seldom included. Said Bien, "The Greek and Latin writers are so much more attractive than the Hebrew authors. The Greeks and Romans were full of life and joy. They had passions and committed crimes, they slept with each other, and bore children, and sang, and played games. The Hebrew writers are dour and moralistic grand but forbidding.")

NO, mental discipline and improved English do not convincingly justify classical studies. Especially not the new, broadened classical studies. The real justification, the one which rings truest, has always rung truest, is found not upon the firm ground of utility but in the misty regions of pleasure. Edward Bradley, who chairs Dartmouth's Classics Department, alludes to the pleasures of classical study in a moving description of it as but one of the liberal arts:

With a couple of exceptions, maybe English grammar and basic arithmetic, there is no inherent reason for studying any of the disciplines of the liberal arts. They are a gratuitous, free, intellectual pursuit. The truest kind of intellectual joy comes from a liberal arts education — equipping yourself with the intellectual means to your own enlargement. Classics in particular has a corpus of very good stuff that can hold its own with the corpus of any other literary tradition, and it has the historical property of being first. A splendor and a potency attach to the tiators. To study them is to know the thrill of being at the fountainhead.

Perkell feels the same thrill: "When I first looked at the funny-looking Greek letters, I thought, 'My god. That's what Sophocles actually wrote!' and I got goosebumps. He and now I were participating in the very beginning moments of our culture."

Being at the beginning also means, say many students of the classics, that you are not taking anyone else's word for what is there. "If you read translations only, you miss something," says Michael Chu '80. "Read two translations and you see that they are never the same. It makes you wonder what you are missing." "There is a deep connection between a culture and its language," adds Ostrow. "It may be a truism, but perhaps you are not able to appreciate the connection until you have the language yourself. It produces a different sensation."

Many, like Wiencke, find the intellectual challenge of learning Greek and Latin not so much a mental discipline as a deep satisfaction. "There is a fascination in the languages themselves. They are more complex than modern languages, and the puzzle is compelling. Then, too, they are valuable for what is,written in them, the ideas. Greek society was so very different from modern industrial society. The ancients wrote in the realm of pure thought. They are always a challenge to the mind," says Wiencke. Bradley speaks with distaste of the modern emphasis on acquiring languages almost exclusively in spoken form and upholds the greater satisfaction of learning to -read and to write another language. "Students come to the 'dead,' or unspoken, languages because they are tired of being treated like parrots in modern language courses," says Bradley. "They want something to sink their teeth into."

Both Rutter and Ostrow attest to the excitement, the romance of discoveries about the physical world of the ancients. "I like doing archaeology," explains Rutter. "No — god, no — it's not a treasure hunt. That's a real insult. It's the puzzle of wrestling with the data." For Ostrow, the historical mysteries are the greatest drawing card. "The more you study the ancient world, the more remote it becomes. It is an ever-increasing mystery. It is so bizarre."

"Why do classics?" said Doenges, with a smile. "Simply because I love it."

WILL the new attractive, intensified, classics in translation offer these deep pleasures? One can see the enlargement of the discipline to include archaeology, history, art, architecture, government, anthropology, sociology — all the modern modes of study — only as a gain for classics students and professors. And as everyone points out, if all you have time for is classics in translation, then do it that way in preference to not doing it at all. The result ought to be a widespread understanding of at least some aspects of classical culture, which will create valuable sympathy for the discipline. But the concomitant watering down of the linguistic and literary study of ancient Greek and Latin is less clearly a good thing. Just how central to a satisfying — and useful — course in the classics is a thorough grounding in the languages? One wonders whether the turning away from linguistic rigor will lead to the slow absorption of departments of classics by departments of history, of anthropology, of religion, of government, of comparative literature.

Evan Haley '77, a product of the new classics, writes that his experience with it "was not all golden" (though he hastens to add that he does not in any way regret having chosen classics as a major):

My interest in the classics began at a time when Greek and Latin were being dropped from the curricula of schools all across the nation. I came to Dartmouth unprepared in both. My knowledge of Roman history enabled me to score high on the Latin CEEB test during freshman week, and, as a result, I was placed in Latin 3, with dire results. We read the Satyricon that fall and it was an excruciating time for me. Undaunted by that experience, I took Latin 2 in the winter and showed considerable improvement. I didn't begin Greek until fall term sophomore year. Beginning Greek was rough. I dare suggest that the brevity of the fall and winter terms impaired basic Greek and Latin instruction.

Just as Latin had been scratched from my high school's curriculum several years before I developed an interest in the classics, mandatory comprehensive examinations, usually reserved for classics majors at Dartmouth in their senior year, had been scratched at Dartmouth before I matriculated. 1 graduated with an A.B. in Greek and Latin not having taken any comprehensives, and there are times when I rue the fact. [A comprehensive exam for classics seniors has recently been re-instituted, on an optional basis.] One problem, in my case, was that I spent senior fall in Italy on the classics foreign study program, which precluded language study. Thus, by the time I normally would have prepped for the comp, it had been six months since I'd been reading Greek and Latin. I can't say that I profited greatly from the Dartmouth Plan respecting my linguistic preparation.

Dartmouth's department is enthusiastic about the new classics and no one wishes to see a return to the old ways. All are agreed that classics should not have a special place in the curriculum. It is right that it should compete on equal terms with the other disciplines, they say; the new classics can hold its own. But if you listen carefully, there is a note of uncertainty about the future. "We are in transition," says Tatum, "but to what is not exactly clear." He is concerned about the tendency for teachers in both schools and colleges to practice "the Greek-and-Latin-in-translation racket" without a knowledge of the languages, which seems to him unfair to students. And he is particularly disturbed by the dislocating effect that the Dartmouth Plan has on the College's sequential studies, such as languages. "Nobody realizes yet," he muses with a furrowed brow, "what's happening to Dartmouth education, and they won't for a while." He pauses. "We're not requiring things," he starts to say, and then his voice trails off.

Illustrations from Ernst Pfuhl, Masterpiecesof Greek Drawing and Painting, London, 1926.

Dartmouth College Museum and Galleries

Shelby Grantham, whose article "JohnnyCan't Write? Who Cares?" appeared in theJanuary 1977 issue, is an assistant editor ofthe ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1978 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureRich and tasty cabinetwork

March 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

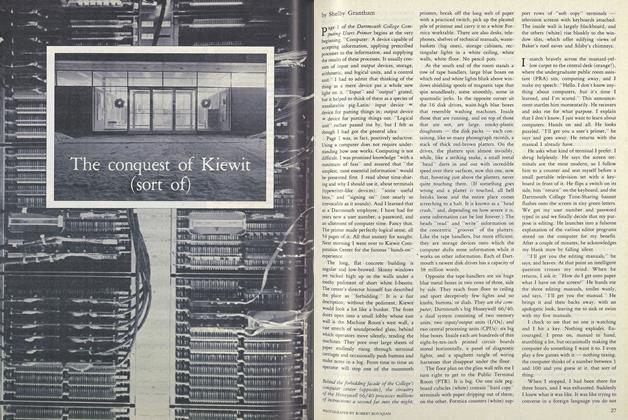

Cover StoryThe conquest of Kiewit (sort of)

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

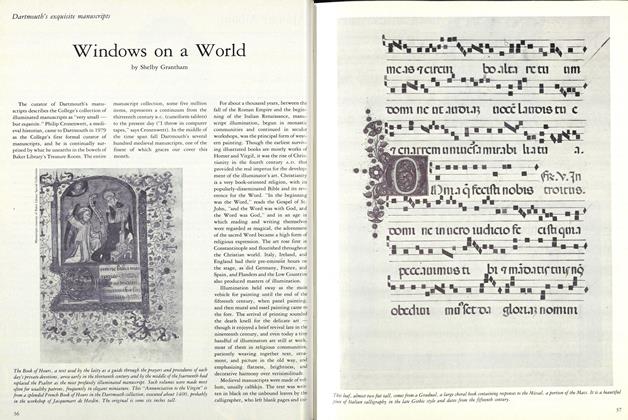

FeatureWindows on a World

DECEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Cultural Look Ahead

MAY 1957 -

Feature

FeatureBronx County Chairman

APRIL 1968 -

Feature

FeatureGame Changer

NovembeR | decembeR By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Sept/Oct 2008 By Kristen STromber '94 -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureI Was A Freshman Trip Spy

September 1993 By Todd Balf