A Damn Yankee and a voyaging Bengal

"You get out there on that grass and it comes down to two people - a pitcher and a man with a bat in his hands - and there don't nothing else matter." The words of Stud Cantrell, a character in Paul Hemphill's book, Long Gone, sum up the essence not just of baseball but of all sport - of the simple confrontation, the challenge offered and accepted. These are the stories of two Dartmouth athletes, both of the class of 1976, who pursued that essence beyond graduation - one in baseball, the other in football.

It is a sunny Saturday morning in February 1979, and snow mantles the trim quadrangles, gabled roofs, and widows' walks of Andover, Massachusetts. Down a dead-end street flanked by stone fences on the campus of Phillips Academy stands Paul Revere dormitory. Inside, Jim Beattie '76 pads barefoot into the living room of the spacious apartment he shares with his wife, Martha Johnson Beattie '76, a math teacher and women's crew coach at the school. He wears baggy, paint- spattered overalls and a blue-striped shirt open over a green turtleneck. A pitcher for the New York Yankees, he is six feet six and as rangy as a long-distance runner. His right arm is lean and sinewy and powerful enough to rifle a baseball to the plate at clocked speeds of up to 92 m.p.h.

As student clatter fills the dorm halls, Beattie gazes out frosted windows, then flashes a tight smile at the mention of upcoming spring training in Florida. "You know, you can tell how coaches feel about you down there," he says, running fingers through reddish hair. "You're either a prospect or you're a suspect."

Since the Yankees drafted him in 1975, Beattie has become every bit the prospect, a status enhanced last autumn when he won four of six games during the Yankees' pennant battle with the Boston Red Sox, pitched an American League playoff win against the Kansas City Royals, then beat the Los Angeles Dodgers to become the first Ivy Leaguer to pitch a complete-game win in the World Series. "I feel I'm one of the Yankees' six starting pitchers," he said last February. "I feel I have the team made." Then he added matter-of-factly: "But the Yankees don't hold on to guys for too long. I see people floundering, and I know they need a good year or they could be gone. That could be me."

Born on the Fourth of July - a birthdate he shares with Yankees majority owner George M. Steinbrenner - Jim Beattie, age 25, takes delight in playing for baseball's most controversial team. Little more than a year ago, on a night he was to pitch, he had to talk his way past the guards at Boston's Fenway Park because he wasn't recognized. Today, people know him. And, says his wife, he feels he belongs. "A lot of people tell me they hate us Yankees," he explains. "But I like being a Damn Yankee. It's nice being a little bit different."

Back in Red Sox-crazy Maine, where the Yankees are as popular as wind sprints, Beattie was an honorable-mention basketball all-America in high school. He played baseball, too, but didn't turn to pitching until he was a junior, switching from third base. At Dartmouth (which, he says, doesn't recruit baseball players and only cottoned to his basketball talents after he had applied), Beattie captained one of the top freshman basketball squads in the East; then as a sophomore and junior he labored on teams rendered mediocre by defections, injuries, and annual coaching turnovers. As an all-Ivy baseball player, he took advantage of the team's lengthy schedule - of up to 50 games - by pitching every five or six days. "That's how [former Dartmouth baseball coach] Tony Lupien prepared me for the rigors of the pros," Beattie says. "He transformed me from a high-school hurler to a baseball pitcher." Following his junior year he signed with the Yankees, and in doing so forfeited his senior eligibility for basketball. "People may ask, 'Why play pro sports with your education?' " Beattie says. "But it was a pragmatic decision. And given the opportunity, what would they do?"

Meanwhile, in three years his classmate and wife-to-be never once saw Beattie play varsity basketball or baseball. "I wasn't exactly high profile," Beattie concedes. "Basketball is an urban game and can't compete with hockey in Hanover. And baseball may be the Great American Pastime, but at Dartmouth it always seemed like people watched it on the way to somewhere else."

An art degree in hand in the fall of his senior year (thanks to extra credits earned in high school), Beattie began his odyssey through pro baseball the following spring - in the minors. In a game where a catcher's mitt is called a "tool of ignorance," no one was too impressed with Beattie's Ivy League background. "The Ivy League?" former Yankee manager Bob Lemon once barked when asked about Beattie's past. "Hell, I thought I'd played in every league and I've never heard of that one." Says Yankee Graig Nettles: "College doesn't mean much on the field. What really counts is a minor-league education." And Beattie has had his fill. "I gave myself three or four years to make it to the big leagues," he says. "Before last year I wasn't sure if I would."

Indeed, his professional career has been fraught with frustration. He has spent the better part of four seasons in the minors, in out-of-the-way tank towns like Oneonta and Syracuse, Ft. Lauderdale and West Haven. To make matters worse, in the summer of 1976 he suffered a shoulder impingement - a tiny bone spur had grown into the shoulder joint - which inflamed tendons and hampered his pitching motion.

The Yankees sent him to several specialists, including Dr. Robert K. Kerlan, medical director of the National Athletic Health Institute, who has also tended to the likes of Olympic gold medalist Bruce Jenner, basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and pitchers Nolan Ryan and Tommy John. "At least the team wasn't looking to the short term," Beattie says. "They were interested in my future value." At one point, George Steinbrenner told him that if pitching hindered his troubled arm he should simply take a year off. He didn't, and it wasn't until midway through the 1977 season that he was pitching without pain.

"Now I'm at the stage a lot of young pitchers are," Beattie says. "Facing better talent, I've got to improve no matter how hard it is to give myself that extra push. In college I had one bad game that I can remember. In the pros I've been bombed a few times. It hurts. You wonder what went wrong."

Beattie describes such incidents with motion-picture vividness, evoking an image of a glum-faced manager stalking out to usher him from the mound. "I relive these mistakes ... the pitch that was hit for a double or a home run. I can ... I'm there. At those times there's a struggle within to retain composure and confidence. Sometimes you feel crummy, but you can't believe you're being yanked because you failed. I don't really fear any batter because I know no matter who's up that I can pitch well and still get killed. I pitched [Boston slugger Jim] Rice perfectly one time and he just took the ball and flicked it over the outfield fence at Yankee Stadium." He shrugs. "It was just one of those things."

When healthy, Beattie relies in large measure upon a curveball and what teammate Catfish Hunter calls, in a Southern drawl, Beattie's "real good-movin' fastball." Yankee manager Billy Martin has voiced the opinion that Beattie can be a 20- game winner. But teammate Ron Guidry, baseball's best pitcher in 1978, says that to do so he must first master the subtle art of control - putting the ball exactly where he wants it to go.

To this end, a battery of minor-league pitching coaches, some of whom scarcely watched him play, have tinkered with his delivery. "Around 1977," Beattie says, "I got in a real muddle." Several coaches helped to improve his technique, but it was Tony Lupien, prior to spring training 1978, who dissolved his confusion. Establish a comfortable style, Lupien instructed, and stick to it. That spring Beattie was voted the outstanding rookie in training camp.

Promoted to the Yankees shortly thereafter, he won his first start - against Baltimore Oriole pitching great Jim Palmer - and was undefeated in five games. Then he floundered, losing seven of eight. Beattie is usually confident ("If you fear failure, you don't know how to win"), but the losing string shook him. "I was battling that fear of failure. I went out thinking not, 'I'm going to win,' but 'I hope I don't lose.' " When he pitched well, the runs didn't come. When they did, he was ineffective. Teammates began to jest that he was jinxed. "I wondered if I'd ever win a game again," he says. In June 1978, against the front-running Red Sox, he hit rock bottom.

Asked before the game if he was pleased with Beattie's pitching, Billy Martin was blunt: "Yes, but he can do better." Asked how, he snapped: "By winning." That night Beattie didn't, giving up four runs in three innings. The next day he was dispatched to the Yankees' minor-league team in Tacoma, Washington. According to former Yankee pitcher Sparky Lyle in his book, The Bronx Zoo, George Stein- brenner labeled Beattie's performance "gutless."

"I said you looked like a scared kid out there," Steinbrenner later told Beattie. "I went to a New England school like you. They don't toughen you up enough." Beattie disagreed: "He went to Williams and came from a wealthy family. I didn't. He didn't need to street-harden me. I'm not an innocent when it comes to the realities of baseball."

After a month in Tacoma, Beattie was recalled to shore the bullpen of the slumping Yankees, then trailing Boston by 14 games. Beattie, who admits to being at his peak late in the season - "when the pressure's on" - was impressive. His four autumn wins included a 10-0 rout of the Red Sox, the club that only a month before had been his undoing, and a crucial last- weekend win against the Cleveland Indians. Then followed the fifth game of the World Series: Without a complete major- league game to his credit, Beattie struck out a career-high eight batters to defeat Los Angeles, 12-2.

Altogether, Beattie had good reason to be confident last February. But, as that ripe adage dictates, in baseball all things are possible in winter. Come spring, the Yankees' signing of free-agent pitchers Luis Tiant and Tommy John and Beattie's own dismal 0-4 start conspired against him. Again he was sent to the minors. "It took me a while to understand why," he says. "I didn't think they could do it to me."

After four straight wins, he was back with the Yankees. Then, in Toronto, he was struck on the pitching hand by a hard line drive and sidelined for almost a month. Finally declared fit in July, he was packed off to the minors, this time to work himself into shape.

The morning after learning of the news, as he readied to leave his New York apartment off Fifth Avenue, Beattie seemed unperturbed, instead willing to chalk up the latest development to the nature of his profession. "Jim probably takes the ups and downs better than I do," says Martha Beattie, who nonetheless appears to have adapted well to the life of a player's wife. Although she summers with her husband in New York - when he's there - and occasionally accompanies him on team trips (paying her own way), there are long stretches when they are apart. "We knew the life we were getting into when we married," she says. "It's a lot better than if Jim were a traveling salesman."

As for Beattie himself, bring up the struggles of Pete Broberg '72, who pitched for five major-league teams in eight years (before being released by a sixth last spring), or the grimly brief length of the average major-league career - only 4.75 years - and he readily concedes the drawbacks of his calling. He has already begun studies toward a business degree at Northeastern University. But this genial man - who dabbles in needlework and takes a sketch pad along on visits to the quaint Connecticut seaport of Mystic - is convinced he will succeed. "I'm not the kind of guy who hangs on when there's nothing left," he says, "but I love this game too much to relinquish it easily." He pauses. "I've had some tough times, sure. But I've just got to keep going. I have a chance to do really well in the business. And I intend to."

Ah, those poor Cincinnati Bengals. Or as a profusion of the team's fans lamented last season, those poor Bad News Bengals. As the Bengals fumbled, stumbled, and otherwise staggered through a wretched 4-12 season, up into the breezes of Riverfront Stadium went banners demanding ticket refunds. It wasn't supposed to happen that way, not to a team that had lost only 16 games in the three previous seasons. Bad news, indeed.

"Sometimes we stunk out there," admits Bengals linebacker Reggie Williams '76, his voice barely above a whisper. "The organization was a real cesspool. Those were rough days - and I'm not saying that so people will go 'boohoo, poor Reggie,' because everybody suffers. Losing like that, week after week, created a period of tremendous self-evaluation for me. Not just in terms of football, but in terms of my life. Was it a life of victory? Or of defeat? Above all, there were lessons to be learned in losing - about myself, other people, about handling stress. And believe me, there's a lot of stress on a losing ball club."

Reggie Williams is an anomalous character in the largely unintellectual world of pro football. Call him cerebral, and he counters that he is simply on a voyage of discovery (a Dartmouth physics professor once lauded him for his "joy in learning"). At 4:00 a.m., an hour when many athletes are climbing into bed, he arises to read C. S. Lewis or Chinese philosophy or perhaps to crack an old college text.

There was a time in the not-so-distant past when Williams paraded his singularity with flamboyance. He drove a sleek Jaguar XJ6. He amassed a closetful of snappy clothes and a collection of some 40 hats. Looking like Edward G. Robinson's sidekick, he once boarded the team plane in a pin-stripe suit and a jaunty fedora, with a shaving kit under one arm - in a violin case. "I was a rookie then," he says. "I've begun to put my values in non- material things." By way of proof, he notes, the Jaguar now belongs to his parents.

Williams is a deeply religious man, and he tries to pray at least an hour every day. "I tried to intellectualize religion most of my life, but faith and rationalization don't mix. Then I realized God was real. Much of what I desired in life was hollow - the money, the fame, the ladies - and football couldn't provide me with the anticipated happiness. I was putting my faith in money which, as the old cliche goes, can't buy happiness."

There is an obbligato fatalism, a tinge of superstition, that accompanies Williams' Christian values. Mention the numbers six and three and he says they surface in his addresses and zip codes and phone numbers with uncanny frequency. His Dartmouth uniform number was 63. His sophomore year the team record was 6-3. His junior year it was 3-6. Before a junior exchange program in California, Williams stayed with an alumnus who took him on a Pacific day cruise aboard the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk. Its number? 63. In 1976, when Williams became the lowest draft pick in Dartmouth football history, he was the Bengals' sixth choice in the third round.

Numerology aside, Williams believes fate handed him a chance to start after he had served on special teams during his rookie preseason. On a crisp October day before a game against Cleveland in 1976, the Bengals were walking through plays wearing only light pads. As veteran linebacker Ron Pritchard, himself a devout Christian, returned to the huddle after a sequence, he collapsed, his knee buckling beneath him. Williams has started every game since.

As a youngster in Flint, Michigan, he had once pointed to running back Jim Brown's image on television and vowed to his father - a former semipro baseball player - that he would see Reggie on that screen one day. Ironically, Williams didn't play organized football until the tenth grade - as third string on the junior varsity. Even then, his participation was partly a ploy to gain social acceptance: As one of few blacks in mainly white college preparatory classes, he was often shunned by his peers. That ceased when after a summer of hoisting weights Williams gained 20 pounds and started for the varsity on both defense and offense. "A startling transformation," he says, understating the case. And one that brought a flood of college offers.

Williams was set on medicine and narrowed his choices to Dartmouth and nearby Michigan. His high-school counselor advised against Dartmouth, saying he would never be accepted and if he were, he would fail miserably. But after a weekend visit to Hanover - during which he discovered he "could get a good education and still have a good time" - Williams proved his counselor wrong.

He eventually abandoned premedicine for psychology. "I didn't have the discipline to play football, slog through premed, and be my own person," he says. "I wanted to develop a social identity, to mingle with other people. Because Dartmouth isn't buildings or classes. It's people." He became president of the black fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha, and even made interpersonal relations the subject of a psychology project. "Reggie is a born communicator," says teammate Pat McInally, a former Harvard all-America who played against Williams in college. "He has a pull all his own, a quiet kind of power. You sense him without him even saying anything."

On the field, Williams became the most honored Dartmouth football player since halfback Bob McLeod was a consensus all- America in 1938: most valuable member of the freshman team, a three-time first-team all-Ivy pick, an American Football Coaches Association all-America as a senior, a member of virtually every all-East and all-New England team named during his last two seasons.

Unlike Jim Beattie, Williams had no stint in the minors to cushion his emergence into the big leagues. To his regret, he was plunged into what he calls the "fishbowl existence" of the pro athlete. "Cincinnati was a far cry from the secluded haven of Hanover," he says. "People always want to know about you - or about who they think you are."

Then there was the matter of the Ivy League stereotype, that of the absorbed scholar with eggshell fragility. It was an image reinforced in Cincinnati by Pat McInally, who missed his rookie year after breaking a leg in the College All-Star Game, then tore the rotator cuff in his shoulder in his first scrimmage the following season. Teammates came to call him "Candle" - one blow and you're out. "I wanted to lay to rest that sort of thing, that Ivy League players aren't tough enough," Williams says. By his habit of hurdling backs and tackles to reach rival quarter- backs (a maneuver that leaves his knees highly vulnerable), Williams has laid more than the idea to rest. "I am a bit reckless," he concedes, "but no one intimidates me. Velocity times mass equals impact, right?"

The Bengals drafted Williams principally for that velocity - his 40 yards in 4.5 seconds is exceptional for a linebacker of his six-foot-one, 230-pound proportions. He employs that quickness to cover opposing offensive backs and wide receivers and to assist his defensive backs on pass coverage.

When Williams argues a call with an official - as he has been known to do - it is a move born not of incivility but of a disdain for half-heartedness. "Reggie is a very intense man," says his agent Mike Slive '62, a Hanover lawyer. "Anybody who gives less than their best won't find him very friendly." Indeed, unless physically drained at game's end, Williams says he feels he has shortchanged the team.

Last year, as the Bengals wallowed through their season of discontent, Williams lashed out through the pages of the Cincinnati Enquirer against what he considered the Bengals' uncaring and inept management, and a lack of effort by some players. "I'm not caught up in the Vince Lombardi concept of winning is everything, but I believe that if you do something, give it 100 per cent. That wasn't happening. Football is important to me, not the least because of the risk involved. I've already suffered chronic injuries. And there'll be more, that's a given. Why should I risk my body if no one cares?"

Such outspokenness is anathema to pro football's managerial rank and file, but it troubles Williams not a whit. This is a man who believes that if Dartmouth has a failing it is that it encourages servility to role models and a reliance upon the opinions of others. "In college I wasn't trying to be a black or a Tom. I was trying to be Reggie. I'm not a conformist. There's already too much conformity in this world."

What most interests him is children, partly because he cherishes their natural independence and respects their basic honesty. One afternoon he and some teammates chanced across a group of youngsters scrimmaging in a Cincinnati park. A boy was injured. As he lay writhing on the ground, a coach walked over, hoisted him to his feet and began screaming that he lacked toughness.

Such callousness toward children troubles Williams greatly. In past years, he has served as a volunteer in a federal program to locate jobs for high-school seniors. This summer he worked for Operation Athlete, spending up to three hours daily with wayward youngsters, many already prison veterans. "A lot of these kids have no one who cares," he says. "I give them my time, the most precious thing I can offer. I don't hold back love, and I try to be as genuine as I can."

Like Jim Beattie, Williams believes his finest years as a professional athlete are before him. Only 25 years old and in his fourth season as a Bengal, he may justify teammates' predictions that he will become one of football's top linebackers. Come what may, this season undoubtedly will be happier if he - and Cincinnati - are able to shed the bitter memories of last year.

Head bowed, Jim Beattie strode intoYankee Stadium with Thurman Munson'sequipment bag slung over his shoulder.Beattie had just flown from Ohio followingthe Yankee captain's death there early inAugust, and it was the first time he hadjoined the team since being dispatched toColumbus. With pitcher Ed Figueroaslated for arm surgery, club officials continually claimed Beattie would be backwith the Yankees "any day now." OnAugust 17, he was called up again, andthat night started against the MinnesotaTwins. Beattie gave up a three-run homerin the fifth inning, and the Yankees lost, 5-2.

Last month, in their first two pre-seasongames, the Cincinnati Bengals beatDetroit, 40-28, and Green Bay, 20-5. Noone is fooled that pre-season games meanvery much, but the Green Bay score was aproud one for the Bengal defense andReggie Williams. For the fleeting moment,which is what the professional athlete livesby, it helped soothe the sufferings of lastyear and offered hope and expectation forthe long season ahead.

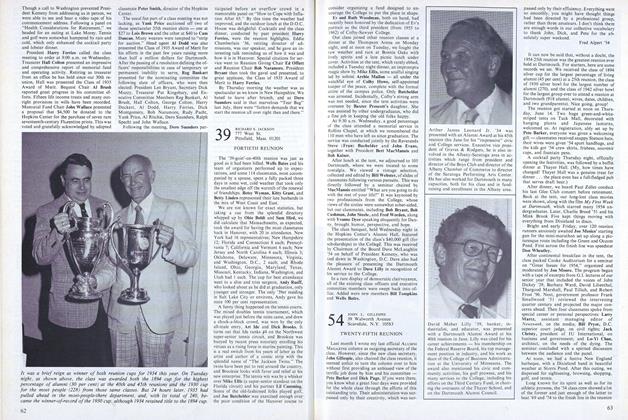

Jim Beattie pitched a classic World Series victory and then became expert on theshuffle. Barbs from Billy Martin and George Steinbrenner became familiar, too.

Reggie Williams has a couple of former foes for teammates, Pat McInally (Harvard)and Dick Jauron (Yale), and a fellow Dartmouth alumnus as assistant general manager, Mike Brown '57. Opposite, Williams of Cincinnati stops Williams of Tampa Bay.

Keith Bellows '74 is editor of Hockey magazine and a free-lance writer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

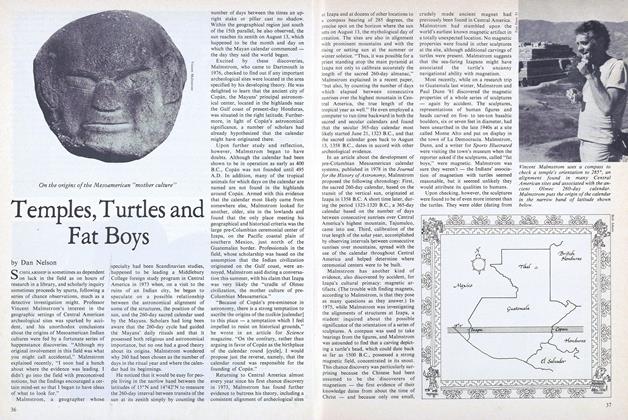

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

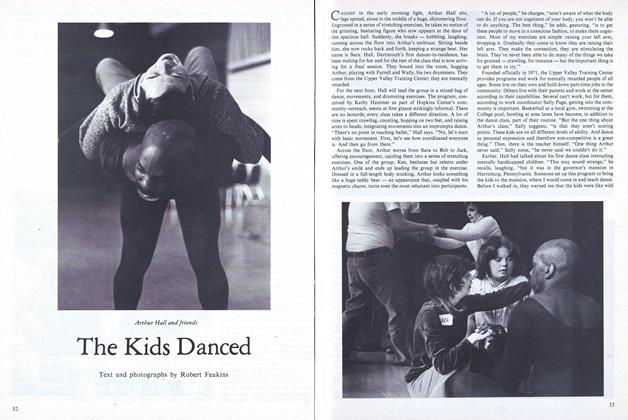

FeatureThe Kids Danced

September 1979 By Robert Feakins -

Article

ArticleThe Bard's American Friend

September 1979 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

September 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE, Fred Alpert '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

September 1979 By WILLIAM B. CATER JR. -

Article

ArticleCarving Out Spaces

September 1979 By Beth Baron '80

Keith Bellows

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Backward Glance at the Humanities

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1961 -

Feature

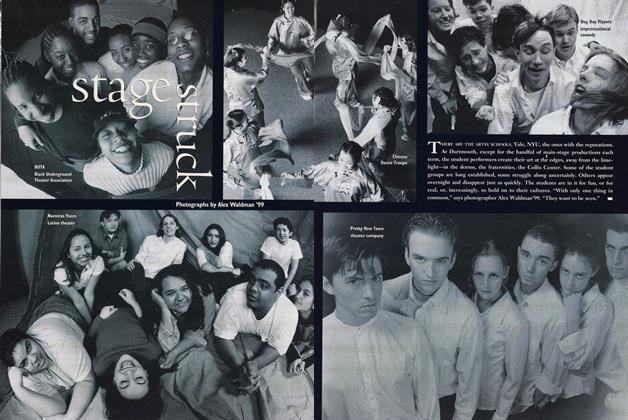

FeatureStage Struck

MAY 1999 -

Feature

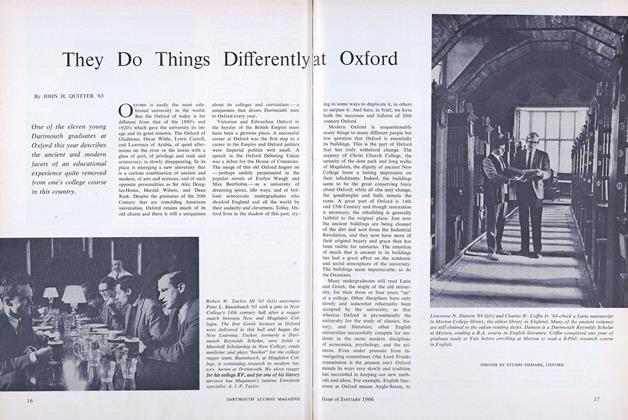

FeatureThey Do Things Differently at Oxford

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN H. QUITTER '63 -

Cover Story

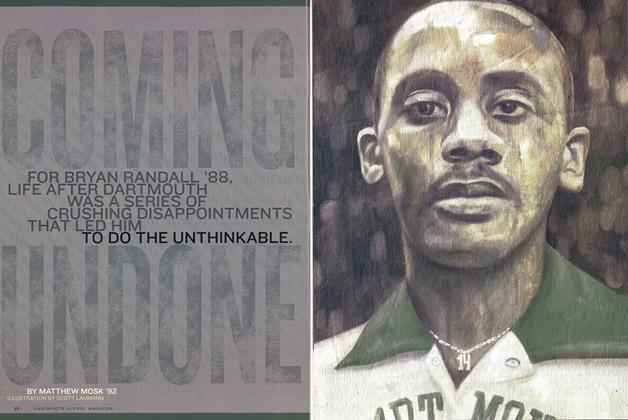

Cover StoryComing Undone

Jan/Feb 2005 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham