FAMILY MATTERS: SAM, JENNIE, AND THE KIDS by Burton Bernstein '53 Summit Books, 1982. 200 pp. $13.95

We have grown used to the family chronicle as a basis for novels, as with Jane Austen, Tolstoy, and ever so many others, where siblings and generations are played off against each other, thereby giving sharp relief to the various characters created. In the field of biography, families with more than one eminence have been given to us with the collective lives of such nuclei as the Brontes or the Jameses. Now Burton Bernstein describes the origins and in many cases the travails of his remarkable generation, with the spotlight on his brother Leonard, the composer and conductor. In most families the past that formed the parents is still an important influence in the manner in which they go on to form their own children, even in the face of changes of venue.

Starting with a family photograph in the family home in the suburbs of Boston, Bernstein goes back into its Hasidic roots in the Ukraine, in a shtetl within the Pale of Settlement. He also conjectures on the origins of the family name, although there is no explanation of why Leonard prefers the Hochdeutsch pronunciation of the suffix (-stine) over the usual Yiddish and equally legitimate pronunciation (-steen). The narration of the family's history in Russia is quite akin to tales from Sholom Aleichem or Isaac Bashevis Singer. The migration of the father, Sam, is unique but in many ways typical and it recalls, although in a different culture, the Ellis Island experiences of Elia Kazan and others.

Courtship and marriage and struggling upward to ultimate success form the next compartment and lay the groundwork for the second and even greater degree of success, that of the American-born children, with stress on Lennie. Although many warts and hairs of the family are revealed, the picture in the end is one of warmth. Bernstein manages to paint a loving portrait without gushing. While the European part of the family history has a natural undercurent of tragedy running through it, the American part is marked by humor. The children delight in their parents' malapropisms, which seem almost too good to be true, as if they had been invented by George S. Kaufman.

In a book as brief as this the biographical material must of needs be rather spare. It is, indeed, more biographical than autobiographical, with Sam, Jennie, and Leonard mainly in the fore. Shirley, the sister, is very hazy and Burton is rather reticent about himself. He does explain this indirectly, however, by showing how much he admired and followed his older brother. The third generation is mentioned, but as the subtitle suggests, this chronicle is meant to cover only two generations. In this way we do feel somewhat deprived when we compare the book to the fat tomes that lay out the lives and fortunes of other family groups. Burton Bernstein has honed his style and stylus at The NewYorker, however, where this material first appeared, and concision is one of his fortes. He can pass on a great deal of information and feeling with a modicum of words.

A disappointment for Dartmouth readers will be the absolute lack of any anecdotes about his college days or how he came to choose Hanover (Lennie went to Harvard). He states that it was at Dartmouth that he decided to be a writer and not a pilot. We, particularly, would like to know more about that decision and if some course or professor or other had anything to do with it. It would be good if he plans to include this part of his life in some future book.

The most recent honor to come Gregory Rabassa'sway was the awarding of an honorary Doctorate of Letters at the 1982 Dartmouth commencement.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

October 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureHome, Home on the Plain

October 1982 By Jeffrey Boffa -

Feature

FeatureCan the Summer?

October 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Sports

SportsAn Irish Connection and a Quaker Shutout

October 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1982 By John King -

Article

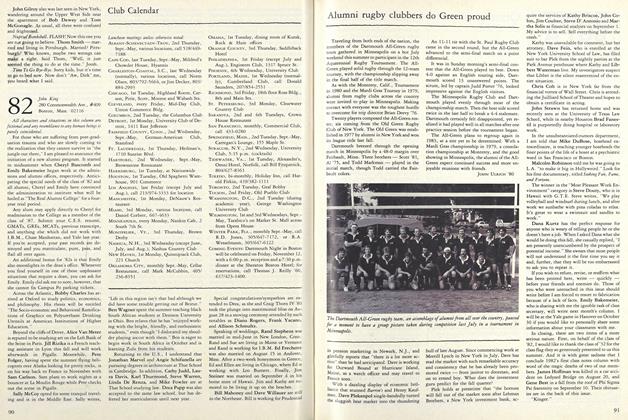

ArticleSexagenarian Hiker Travels Light on the Appalachian Trail

October 1982 By D.C.G

Gregory Rabassa '44

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

February 1939 -

Books

BooksSHADOWS ON THE LAND — AN ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY OF THE PHIL IPPINES.

MAY 1964 By ALBERT S. CARLSON -

Books

BooksTRISTRAM BENT

May 1940 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

BooksTHE HAND IN THE PICTURE,

November 1947 By Eric P., THEODORE KARWOSKI -

Books

BooksON THE STAKED PLAIN

June 1940 By Mabel L. Seavey -

Books

BooksFaculty Books

December 1953 By Robert O. Blood Jr. '42