MEN AT MIDLIFE by Michael P. Farrell and Professor Stanley D. Rosenberg Auburn House, 1981. 242 pp. $19.95

One of the dubious bounties of the "Me Generation" is "pop psychology," an apparently inexhaustible melange of books, articles, pre-packaged experiences and the like, advanced by self-proclaimed authorities, each pushing one small idea for all its worth. This phenomenon is founded on the notion that we are in some ways important sources of our own unhappiness, making it seem downright common-sensical to endeavor to get "rid of our hang-ups." Consequently, a ready market awaits those with plausible sounding, pre-fabricated "insights" into the self. These awarenesses are well packaged and marketed; they require little effort from the purchaser, who anticipates learning all about himself from someone who doesn't know him.

Riding the crest of this wave of popularization are concepts such as "the male midlife crisis," which has come to achieve the status of an article of faith.

In the face of this, two disciplined social scientists - one a Professor of Psychiatry at the Dartmouth Medical School - have released a report of their decade of research (under the not-very-sexy title, Men at Midlife) concluding that there is no such thing as a universal or even typical "male midlife crisis. Indeed, in their carefully designed study and reasonable discussion, Professors Farrell and Rosenberg have found that men respond in a variety of ways to accumulating stresses throughout their livet and that the most important determinants of their response are their pre-existing personalities, family ties, and cultural influences.

Their report doesn't promise you a rose garden, it doesn't legitimize your making a pass at the baby-sitter. Burt Reynolds won't be bidding for the movie rights. But there it is, and it makes solid if not trendy sense.

Though, in all likelihood, the book unfortunately will do little to curb the extravagances of the aforementioned "authorities," it is intelligent, coherent, and delightfully devoid of jargon. Beyond that, its readability comes from the discriminating use of disguised case studies to convey a narrative, human dimension with false dramatics. Since Farrell and Rosenberg come from the neighboring but separate disciplines of sociology and social psychology and are at geographically discrete institutions as well, the apparently effortless blending of perspective in their report undoubtedly indicates significant collaborative work.

Some specific findings will convey a sense of the study's feel for men at midlife. Most men were seen to drift from their original families toward their wives' families in the early years of marriage. They are more likely to live with them, idealize their style and values, and spend important holidays with them. Although they often later resume a more intense dialogue with their own fathers, early in marriage men frequently reduce contact with their parents to a minimum. The reasons for this shift in allegiance are complex, but they include the man's need to complete his separation from his parents, his wife's greater efforts to maintain kinship ties, and, also important, the feeling that it is not "manly" to rely on one's own parents but that it is "womanly" to retain such bonds.

Another intriguing finding is that, although the personal styles of couples studied were quite similar at the outset, they consistently showed a tendency toward polarization as years went by. It seems that mates were chosen as comfortable, like- minded partners but over the years became identified with opposite positions on conflictual matters. The differentiation on any issue usually followed cultural stereotypes: the male being aggressive and adventurous; the woman being passive, nurturant, and conciliatory.

In general, Farrell and Rosenberg are impressed with the role of stereotyping in impoverishing the emotional lives of their subjects. They find it interfering with intimacy between husbands and their wives, the latter generally being pressed into supporting their husbands' rigid and implausible images. Isolation from friends and, ultimately, self-estrangement also grew out of the men's forced efforts to act and try to feel "like men."

Consideration of these and related topics should be of more than passing interest to Dartmouth men who are grappling with he meanings of middle age, changing family ties, masculine stereotypes, and departing children.

In this book they will find themselves in the company of two thoughtful and reflective men who are themselves reaching midlife and are trying to understand,to teach, and to wonder about troublesome issues in men's development rather than to capitalize upon these concerns.

Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry atHarvard Medical Shool and a private practitioner of psychiatry in the Boston area, Dr.Glass was author of a recent article in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE on stereotypes at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

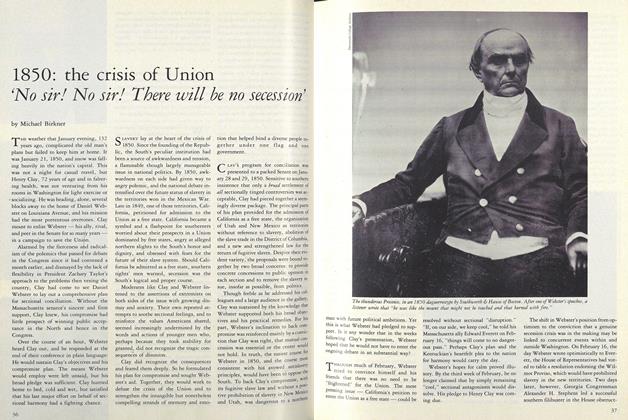

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

March 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

March 1982 By George Kennan -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

March 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

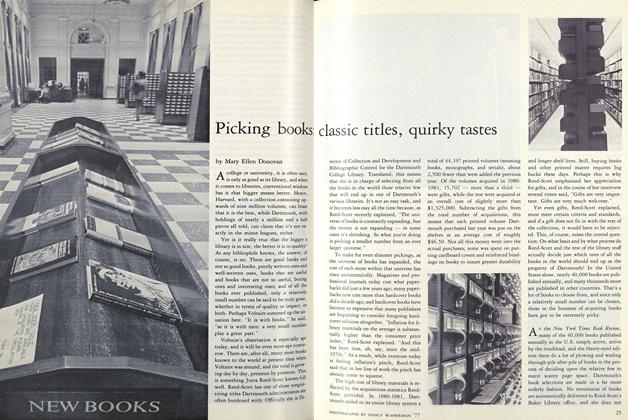

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

March 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Article

ArticleSomeone wrote them, but did anyone read them?

March 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

March 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Graphic Arts in Belgium

November 1938 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

December 1946 -

Books

BooksPREPOSTEROUS PAPA.

January 1960 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksWITHIN THESE BORDERS.

January 1954 By JOSEPH B. FOLGER '21 -

Books

BooksSo Much More

NOVEMBER 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksTHINK ON THESE THINGS,

May 1942 By Roy B. Chamberlin