THE speakers included medical experts, industrial counselors, and concerned faculty, but the majority were alcoholics, come to be heard and counted and questioned. On the stage in Cook, across tables in Collis, over cider, wine, and cheese at Murdough, the alcoholics confronted the long-acquiescent society whose underbelly they know so well. They told tale after gory tale - without breast-beating, bitterness, or sanctimony, and with a lot of leavening wit (dry, very dry). There was an enchanting selflessness in the way the tellers some Dartmouth, some not - gave of their grim and hard-earned knowledge.

It was both shock and inspiration to realize how many of the people one lives and works with everyday have been to hell and come back to tell the tale.

This was at a conference on alcoholism held at Dartmouth at the end of January. The brainchild of Susan McGrath of the College's Public Affairs Center, it was no low-key mimeographed affair, but a fullscale effort including exhibits all around campus, a glossy program, and speakers from all over. Documentaries and feature films concerning alcoholism ran afternoons and evenings for a fortnight around the three-day core of workshops, lectures, and panel discussions; pina coladas made with everything but the alcohol were offered for sampling; and the local constabulary loaned its breathalizer for participants to experiment with.

It is common knowledge that one in ten Americans is an alcoholic, but unfleshed statistics slide quickly off the surface of the mind. At the conference, easily-mouthed catch phrases such as "alcoholism is a disease" took on new meaning as speaker after speaker introduced himself or herself and added, "I am an alcoholic." Sometimes it was "recovering alcoholic," or "arrested alcoholic," but no one ever said, "I was an alcoholic."

The desire to drink seldom leaves an alcoholic, as was graphically explained by a member of the Hanover Young People's Group of Alcoholics Anonymous: "My wife is a social drinker. I can't comprehend that. I just can't. Someone can ask her whether she wants a drink and she actually has to stop and think whether she does or not. She can go to the grocery store and forget to buy beer! I haven't had a drink in years, but a room with a bottle in it is still like a room with a naked person in it hard to ignore." Someone else quoted "Dr. Bob" Smith '02, A.A. Co-founder: "I still think a double scotch would taste awfully good. If it wouldn't produce disastrous results, I might try it. I don't know. I have no reason to think that it would taste any different - but I have no legitimate reason to believe that the results would be any different, either."

The disease whose most stunning effect is often the strength it gives its victims to deny they have it - is fundamen- tally a matter of physiology. People who have trouble with alcohol are people whose physical chemistry will not tolerate alcohol. That is a fact with as much finality about it as the diabetic's intolerance of sugar.

A telling number of questions were asked about how one defines alcoholism, as audiences sought a quantitative yardstick by which to confirm or deny their own or others' illness. Clinical psychiatrist Robert Landeen tried to oblige with an estimate of the "healthy range" of alcohol consumption. Though it is somewhat dependent on size and blood volume, he said, biological processes will not suffer under a regimen of two one-ounce drinks per day every day. But as to what alcoholism is, rather than what it is not, the doctor was, perforce, less precise: "The gross definition is longterm unpredictable or compulsive drinking that interferes with psychological and social behavior. There is a list of 93 symptoms, but it's not as clear as divorce or pneumonia." Alcoholic Barnes Boffey of Dartmouth's Education Department was more colorful, if no more cut and dried. "I look," he said, "for an unnatural relationship to alcohol. I know it sounds natural around here to say, 'Let's go get drunk, drink until we throw up!' But if you examine that in the light of an analogy 'Let's go eat marshmallows until we throw up!' - you begin to see the unnaturalness of it."

Though the base line linking the many alcoholics who spoke out at the conference was the physiological fact of alcohol intolerance, other common experiences surfaced. Time and again speakers cited paralyzing social insecurity and a frantic need to please others. "Without drinks, I didn't feel able to ask Mary to dance," recalled former N.F.L. linebacker Carl Eller. Businesswoman Ann Lutter remembered wincingly how vital it seemed that everybody like her and how little faith she had inside that she was, in fact, likable. Gus Wedell '54, former president of the country's oldest legal distillery, recalled his desperate pursuit of "success" in these terms: "I wouldn't say. no to anything. I said yes because I wanted you to like me - Christ, I wanted you to like me so bad! My head was saying I was doing great, but my gut was frightened. Inside was Jello. I had no idea what people really thought of me, and to take care of the fear, I medicated it" Another recalled that when he was 13 and "the one big thing was to be cool, anyway you could be," alcohol had been the magic cure for all social nervousness.

Not surprisingly, peer pressure and the cultural association of hard drinking with masculinity cropped up as well. Eller described his experience of the drinking games common among teammates in the N.F.L., where the ability to hold liquor was the measure of manhood. Skidmore chaplain Tom Davis '56 traced his alcohol problem back to the same yardstick in a literary context undergraduate emulation of Ernest Hemingway. Sandra McCulloch, alcoholic daughter of Dartmouth Trustee Norman McCulloch '50 (himself an alcoholic), explained how that cultural standard filters right down through the hierarchy, crossing gender lines with impunity: "I had my first drink at ten, and at eleven I was proud of the fact that I could drink any Dartmouth senior under the table. Women are supposed to be closet drinkers, but not me. The only place I didn't drink was in the closet. Drugs, too. All my life I had disliked myself and felt insecure, and I learned that if you have cocaine, you have lots of friends, with no effort. 'This is my fifth head of acid tonight,' I would say to people and think that was really strong and intelligent. I guess I was a real 'mach-ette.'"

Frequent, too, were accounts involving the medical profession's head-in-the-sand attitude toward the disease, an attitude the organizers hope conferences such as this one may help to change. Eller described reaching a point at which cocaine and alcohol were his real career and ballplaying only his stabilizer. He changed teams, he got divorced, he found himself alone a lot, and he became deeply depressed. When finally he sought help from the team doctor, he was told he wasn't getting enough rest and given sleeping pills.

The most incredible of such reports came from Davis, who suffered ferquent alcoholic seizures, attacks similar to those of epilepsy. "With the first one, he said, "I gave the doctor a hint. Not much, you understand - just a sporting chance. I said I was drinking a little. He looked at the results of my electroencephalogram and said he was happy to report I had no disease. And as for the other matter, he said, you just behave yourself and that'll be all right. He was clearly embarrassed by the subject. During my next seizure, I found my arms moving by themselves in the emergency room, and I got scared. Those doctors discharged me without telling me or my wife anything. The next time, I told the endocrinologist that I was drinking a lot. He patted me on the shoulder and said, That's just because you're worried about your health. If we knew what was causing these seizures, you'd be fine.' "

But there common threads parted, and the histories took every turn imaginable. One alcoholic reported that she seldom drank and never had a problem with alcohol until her last child had grown and left home: "Then it became easy to have a drink before supper, which after a bit became a drink instead of supper, and then a lot of drinks instead of supper and breakfast. It took me only three years to go so far down the tube I thought I would never get out." In another woman, the disease took the form of tying one on good and proper and staying drunk for a week three times a year.

Davis's drinking was not the result of any disappointment, he said, nor did he ever risk losing his job or his wife because of it. He just decided one day that sherry for breakfast would be a good idea. (His wife, now a skilled alcohol counselor, was then, he said, merely a Southern Baptist who had been raised in a dry home and had no idea whether sherry for breakfast was strange or not.) One young alcoholic told how he came from generations of alcoholics and paid no attention to his own drinking until he realized with horror that the birth of his daughter had raised no emotion whatsoever in him: he just wanted another drink. Another "majored in drinking in college and became, he said, cheat, sneak, and thief as he went from blackout to blackout for ten years.

Businessman Wedell relied on alcohol in the pursuit of "success," which he found he didn't want and couldn't handle when he got it. Attorney Norman Carpenter '53, on the other hand, hit his alcoholic nadir and climbed up again, at 48, without ever endangering his career. One young alcoholic described himself as an over-achiever and a model student, a winner of the American Legion award for citizenship, and said he felt that because of psychological predisposition and cultural reinforcement, he had been an alcoholic at 17, before he had ever touched a drink.

"WHY Dartmouth?" a lot of people asked, somewhat defensively. Why, indeed. Some time back the College figured out that it had a serious alcohol problem on campus. So, it found, did most United States colleges and universities, and to about the same extent. Which is not so much to say that it isn't all that bad at Dartmouth as it is to say that it is bad all over. Those who put together the conference felt, simply, that Dartmouth has a deep responsibility to do what it can to address a problem of such magnitude. Blame, individual or institutional, was not on the conference agenda, nor was temperance (which was never considered as a solution to anything). Two likely solutions were articulated at the final session,

"Where Do We Go From Here?" One was a heartfelt recommendation to all to make one small but vital attitudinal shift: never plan a social occasion without giving as much thought to the non-alcoholic drinks on hand as to the alcoholic ones.

The other was education: consciousnessraising about the realities of the disease of alcoholism, in particular about its reversibility. "I honestly don't think you can prevent alcoholism," said one young alcoholic fervently. "God help those who try to prevent it. But you can treat it, and education is the key." With that others agreed, lamenting the prevalence of myths about alcohol and the dearth of accurate information about such basic things as the early warning signs of the disease. They went on to urge education without moralizing and education early. "Don't wait until they are 14 and 15," pleaded a young alcoholic father. "My four-year-old knows about alcoholism. I'm not scaring her with it, just seeing that she knows what it is."

Norman Carpenter '53 wrote a "Vox" columnfor the ALUMNI MAGAZINE of May 1976 inwhich he urged the College to manifest someawareness of the problem of alcoholism. Fromthat seed grew this conference, at which Carpenter recalled with sadness, "All during my yearsat Dartmouth, no one ever told me I was drinking too much or that I was behaving badly."

Wedell: "Everyone thought I was thegreatest thing since sliced bread. But inside wasJetto."

Eller: "I discovered I had adisease, and it could be treated. "

McCulloch: "The only thing I never did washeroin — because I had heard that it wasaddictive."

McCulloch: "We have got to recognizethe need to talk about alcoholism openly."

Lutter: "I thought I was being lousy ateverything — and I was. But I thought Icouldn't change it."

Davis: "We cansolve our problems through chemicals, or throughpeople, that choice is always going on."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

March 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

March 1982 By George Kennan -

Cover Story

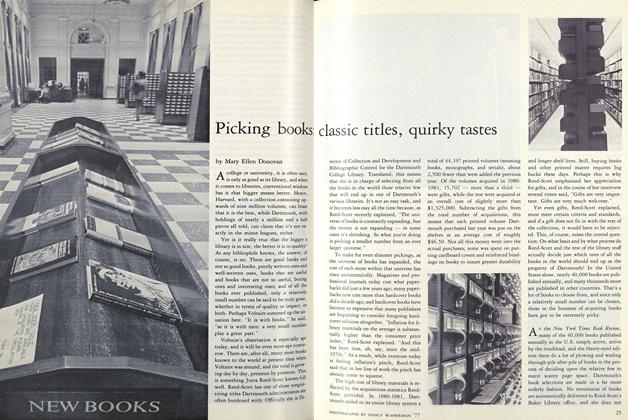

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

March 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Article

ArticleSomeone wrote them, but did anyone read them?

March 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

March 1982 By John L. Gillespie -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1982 By William G. Long

Shelby Grantham

-

Article

ArticleMagic in the Museum

Jan/Feb 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

DECEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

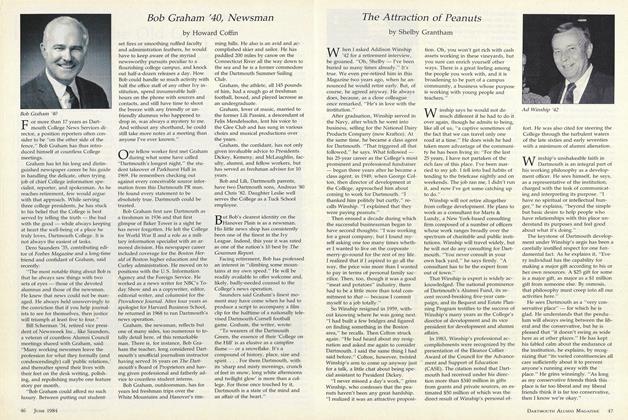

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHopkins Center Inaugural Program

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Alumni Council's 50th Year

JULY 1963 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Alumni College

FEBRUARY 1973 -

Feature

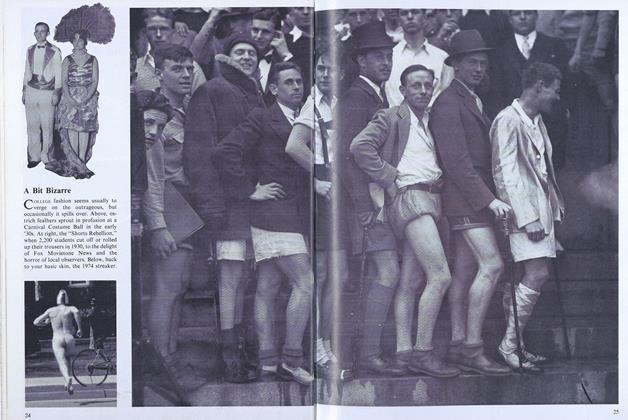

FeatureA Bit Bizarre

December 1976 -

Feature

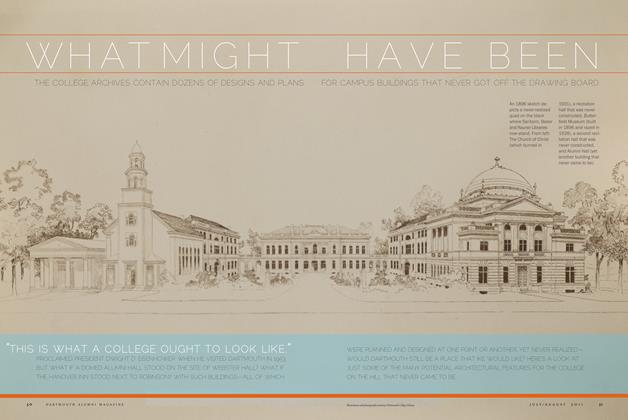

FeatureWhat Might Have Been

July/August 2011 -

Feature

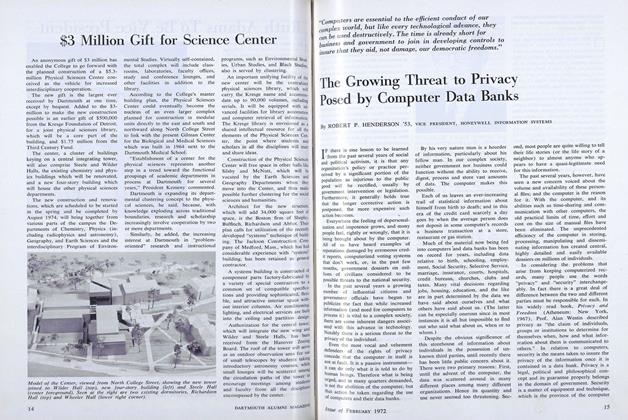

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

FEBRUARY 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53