THE gathering strength of the anti-nuclear-war movement here and in Europe is to my mind the most striking phenomenon of the beginning of the l980s. It is all the more impressive because it is so extensively spontaneous. It has already achieved dimensions which will make it impossible for the respective governments to ignore it. It will continue to grow until something is done to meet it.

Like any other great spontaneous popular movement, this one has, and must continue to have, its ragged edges and even its dangers. It will attract the freaks and the extremists. Many of the wrong people will attach themselves to it. It will wander off

The author, whose writings on internationalaffairs have twice won the "Pulitzer Prize andalso the National Book Award, was an architect of the Marshall Plan (he received an honorary degree from Dartmouth in 1950), ambassador to Russia in 1952, and a Soviet specialistfor the State Department for a quarter century.Presently, he is professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

This article is adapted from a speech given at in many mistaken directions. It already shows need of leadership and of organizational centralization.

But it is idle to try to stamp it, as our government seems to be trying to do, as a Communist-inspired movement. Of course Communists try to get into the act. Of course they exploit the movement wherever they can. These are routine political tactics. Actually, I see no signs that the Communist input into this great public reaction has been of any serious significance.

Nor is it useful to portray the entire European wing of this movement as the expression of some sort of vague and naively

Dartmouth in November, when AmbassadorKennan received the 1981 Grenville ClarkPrize. The prize is awarded every three years inmemory of statesman-author Grenville Clark,whose papers are in the Dartmouth library. Hedevoted much of his later life to a quest for peacethrough international law, after being asked bySecretary of War Henry Stimson in 1944 tostart thinking about how to "prevent WorldWar III." neutralist sentiment. There is some of that, certainly; but where there is, it is largely a reaction to the negative and hopeless quality of our own Cold War policies, which seem to envisage nothing other than an indefinitely increasing political tension and nuclear danger. It is not surprising that many Europeans should see no salvation for themselves in this sterile perspective and should cast about for something that would have in it some positive element, some ray of hope.

Nor does this neutralist sentiment necessarily represent any timorous desire to accept Soviet authority as a way of avoiding the normal responsibilities of national defense. The cliche of "better Red than dead" is a facile and clever phrase, but actually no one in Europe is faced with such a choice, or is likely to be. We will not be aided in our effort to understand Europe's problems by distortions of this nature. Our government will have to recognize that there are a great many people who would accept the need for adequate national defense but who would emphatically deny that the nuclear weapon, and particularly the first use of that weapon, is anything with which a country could conceivably defend itself.

No, this movement against nuclear armaments and nuclear war may be ragged and confused and disorganized, but at the heart of it lie some very fundamental, reasonable, and powerful motivations- among them a growing appreciation by many people for the true horrors of a nuclear war; a determination not to see their children deprived of life and their civilization destroyed by a holocaust of this nature; and finally, as Grenville Clark said, a very real exasperation with their governments for the rigidity and traditionalism that cause those governments to ignore the fundamental distinction between conventional weapons and the weapons of mass destruction and prevent them from finding, or even seriously seeking, ways of escape from the fearful trap into which the nuclear cultivation of weapons is leading us.

Such considerations are not the reflections of Communist propaganda. They are not the products of some sort of timorous neutralism. They are the expression of a deep instinctive insistence on sheer survival —on survival as individuals, as parents, and as members of a civilization.

Our government will ignore this simple fact at its peril. This movement is too powerful, too elementary, and too deeply embedded in the human instinct for selfpreservation to be brushed aside. Sooner or later, and the sooner the better, all the governments on both sides of the EastWest division will find themselves compelled to undertake the search for positive alternatives to the insoluble dilemma which any suicidal weaponry presents.

Do such alternatives exist?

Of course they do. One does not have to go far to look for them. A start could be made with deep cuts in the long-range strategic arsenals. There could be a complete denuclearization of Central and Northern Europe. One could accept a complete ban on nuclear testing. At the very least, one could accept a temporary freeze on the further build-up of these fantastic arsenals. None of this would undermine anyone's security.

These alternatives, obviously, are not ones that we in the West could expect to realize all by ourselves. I am not suggesting any unilateral disarmament. Plainly, two - and eventually more than two - will have to play at this game.

Even these alternatives would be only a beginning, but they would be a tremendously hopeful beginning. What I am suggesting is that one should at least begin to explore them - and to explore them with a good will and a courage and an imagination the signs of which I fail, as yet, to detect on the part of those in Washington who have our destinies in their hands.

This, then, in my opinion, is what ought to be done - what will, in fact, have to be done. But I must warn that for our own country the change will not come easily, even in the best of circumstances. It is not something that could be accomplished in any simple one-time decision. What is involved for us in the effort to turn these things around is a fundamental and extensive change in our prevailing outlooks on a number of points along with an extensive restructuring of our entire defense posture.

What would this change consist of?

WE would have to begin by accepting the validity of two very fundamental appreciations. The first is that there is no issue at stake in our political relations with the Soviet Union - no hope, no fear, nothing to which we aspire, nothing we would like to avoid - which could conceivably be worth a nuclear war, which could conceivably justify the resort to nuclear weaponry. The second is that there is no way in which nuclear weapons could conceivably be employed in combat that would not involve the possibility - and indeed the prohibitively high probability - of escalation into a general nuclear disaster.

If we can once get these two truths into our heads, then the next thing we shall have to do is to abandon the option of the first use of nuclear weapons in any military encounter. This flows with iron logic from the two propositions I have just enunciated. The insistence on this option of first use has corrupted and vitiated our entire policy on nuclear matters ever since such weapons were first developed. I am persuaded that we shall never be able to exert a constructive leadership in matters of nuclear-arms reduction or in the problem of nuclear proliferation until this pernicious and indefensible position is abandoned.

Once it has been abandoned, there will presumably have to be a far-reaching restructuring of our armed forces. The private citizen is, of course, not fully informed in such matters; and I make no pretense of being so informed. But from all that has become publicly known, one can only suggest that nearly all aspects of the training and equipment of those armed forces, not to mention the strategy and tactics underlying their operation, have been affected by the assumption that we might have to fight - indeed, would probably have to fight - with nuclear weapons, and that we might well be the ones to inaugurate their use. A great deal of this would presumably have to be turned around - not ail of it, but much of it nevertheless. We might, so long as others retained such weaons, have to retain them ourselves for purposes of deterrence and reassurance to our people. But we could no longer rely on them for any positive purpose even in the case of reverses on the conventional battlefield, and our forces would have to be trained and equipped accordingly. Personally, this would cause me no pain. But let no one suppose that the change would come easily. An enormous inertia exists here and would have to be overcome; and in my experience there is no inertia, once established, as formidable as that of the armed services.

There is something else that will have to be altered if we are to move things around and take a more constructive posture; and that is the view of the Soviet Union and its peoples to which our governmental establishment and a large part of our journalistic establishment have seemed recently to be committed.

On this point, I would particularly like not to be misunderstood. I do not have, and have never had, sympathy for the ideology of the Soviet leadership. I recognize that this is a regime with which it is not possible for us to have a fully satisfactory relationship. I know that there are areas of interaction where no collaboration between us is possible, just as there are other areas where we can collaborate. There are a number of Soviet habits and practices which I deeply deplore and which I feel we should resist firmly when they impinge on our interests. I recognize, furthermore, that the Soviet leadership does not always act in its own best interests - that it is capable of making mistakes (just as we are) and that Afghanistan is one of those mistakes, one which it will come to regret regardless of anything we may do to punish it.

Finally, I recognize that there has recently been a drastic and very serious deterioration of Soviet-American relations - a deterioration to which both sides have made their unhappy contribution. This, too, is something which it will not be easy to correct, for it has led to new commitments and attitudes of embitterment on both sides. An almost exclusive militarization of thinking and discourse about Soviet-American relations now commands the behavior and the utterances of statesmen and propagandists on both sides of the line - a militarization which, it sometimes seems to me, could not be different if we knew for a fact that we were unquestionably to be at war within a matter of months.

All this being said, I must go on and say that I find the view of the Soviet Union that prevails today in our governmental and journalistic establishments so extreme, so subjective, so far removed from what any sober scrutiny of external reality would reveal, that it is not only ineffective but dangerous as a guide to political action. This endless series of distortions and oversimplifications; this systematic dehumanization of the leadership of another great country; this routine exaggeration of Moscow's military capabilities and of the supposed iniquity of its intentions; this daily misrepresentation of the nature and the attitudes of another great people - and a long-suffering people at that, sorely tried by the vicissitudes of this past century; this ignoring of their pride, their hopes, yes, even of their illusions (for they have their illusions, just as we have ours, and illusions, too, deserve respect); this reckless application of the double standard to the judgment of Soviet conduct and our own; this failure to recognize the communality of many of their problems and ours as we both move inexorably into the modern technological age; and this corresponding tendency to view all aspects of the relationship in terms of a supposed total and irreconcilable conflict of concerns and aims: these, believe me, are not the marks of the maturity and realism one expects of the diplomacy of a great power. They are the marks of an intellectual primitivism and naivete unpardonable in a great government - yes, even naivete, because there is a naivete of cynicism and suspicion just as there is a naivete of innocence.

We shall not be able to turn these things around as they should be turned on the plane of military and nuclear rivalry until we learn to correct these childish distortions; until we correct our tendency to see in the Soviet Union only a mirror in which we look for the reflection of our own superior virtue; until we consent to see there another great people, one of the world's greatest, in all its complexity and variety, embracing the good with the bad - a people whose life, whose views, whose habits, whose fears and aspirations are the products, just as ours are the products, not of any inherent iniquity but of the relentless discipline of history, tradition, and national experience. Above all, we must learn to see the behavior of the leadership of that people as partly a reflection of our own treatment of it. Because if we insist on demonizing the Soviet leaders - on viewing them as total and incorrigible enemies, consumed only with their fear or hatred of us and dedicated to nothing other than our destruction - that, in the end, is the way we shall assuredly have them.

These, then, are the changes we shall have to make - the changes in our concept of the relationship of nuclear weaponry to national defense, in the structure and training of our armed forces, and in our view of the distant country which our military planners seem to have selected as our inevitable and inalterable enemy - if we hope to reverse the dreadful trend towards a final nuclear conflagration. It is urgently important that we get on with these changes. Time is not waiting for us. The fragile nuclear balance that has prevailed in recent years is being undermined, not so much by the steady build-up of the nuclear arsenals on both sides (for they already represent nothing more meaningful than absurd accumulations of overkill), but rather by technological advances that threaten to break down the verifiability of the respective capabilities and to stimulate the fears, the temptations, and the compulsions of a "first strike" mentality.

IT is important for another reason, too, that we get on with these changes. Far beyond all this, beyond the shadow of the atom and its horrors, there lie other problems - tremendous problems that demand our attention. There are the great environmental complications now beginning to close in on us: the question of what we are doing to the world oceans with our pollution, the problem of the greenhouse effect, the acid rains, the question of what is happening to the topsoil and the ecology and the water supplies of this and other countries. There are the profound spiritual problems that spring from the complexity and artificiality of the modern urban-in- dustrial society - problems that confront both the Russians and ourselves, and to which neither of us has as yet responded very well. One sees on every hand the signs of our common failure. One sees it in the cynicism and apathy and drunkenness of so much of the Soviet population. One sees it in the crime and drug abuse and general decay and degradation of our city centers. To some extent not entirely, but extensively — these failures have their origins in experiences common to both of us.

They, too, will not wait, Unless we both do better in dealing with them than we have done, even the banishment of the nuclear danger will not help us very much. Can we not cast off our preoccupation with sheer destruction, a preoccupation that is costing us our prosperity and preempting the resources that should go to the progress of our respective societies? Is it really impossible for us to cast off this sickness of blind military rivalry and to address ourselves at long last, in all humility and in all seriousness, to setting our societies to rights?

For this entire preoccupation with nuclear war is a form of illness. It is morbid in the extreme. There is no hope in it, only horror. It can be understood only as some form of subconscious despair on the part of its devotees - a readiness to commit suicide for fear of death, a state of mind explicable only by some inability to face the normal hazards and vicissitudes of the human predicament, a lack of faith, or perhaps a lack of the very strength that it takes to have faith, where countless generations of our ancestors found it possible to have it. '

I decline to believe that this is the condition of the majority of our people. Surely there is among us, at least among the majority of us, a sufficient health of the spirit - a sufficient affirmation of life, of its joys and excitements together with its hazards and uncertainties to permit us to slough off this morbid preoccupation, to see it an discard it as the sickness it is, to turn our attention to the real challenges and possibilities that loom beyond it, and in this way to restore to ourselves a sense of confidence and belief in what we have inherit and what we can be.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

March 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

March 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

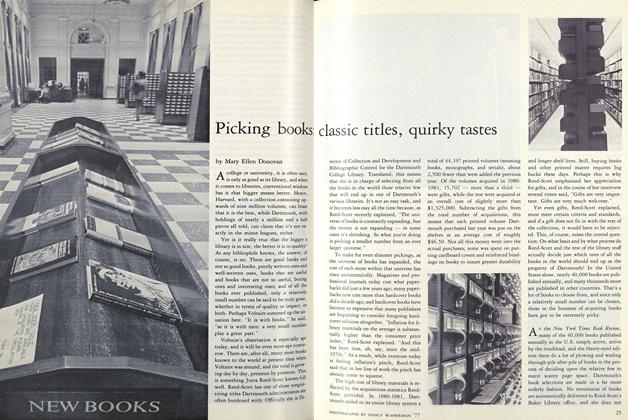

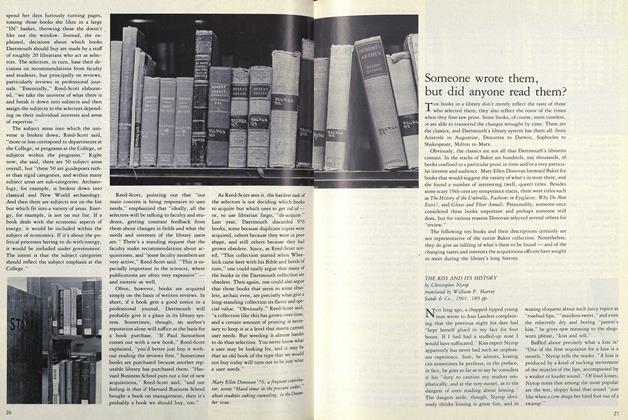

Cover StoryPicking books Classic title, quirky tastes

March 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Article

ArticleSomeone wrote them, but did anyone read them?

March 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

March 1982 By John L. Gillespie -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1982 By William G. Long

Features

-

Feature

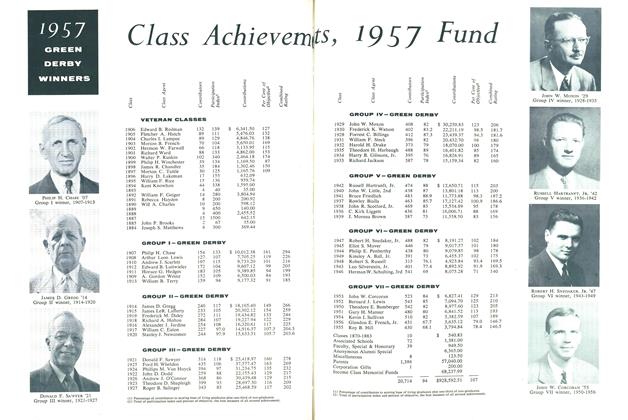

FeatureClass Achievemts, 1957 Fund

December 1957 -

Feature

Feature3. AIDS

December 1987 -

Feature

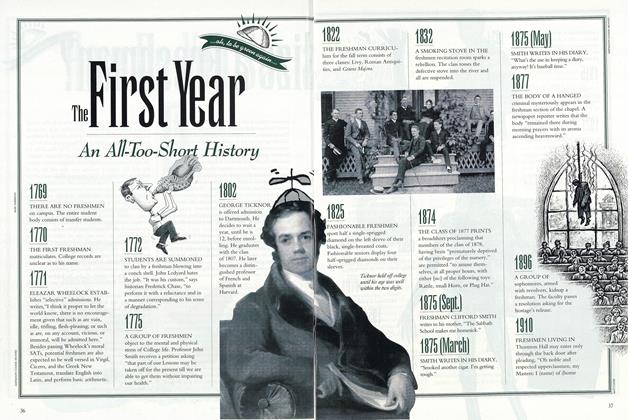

FeatureThe First Year

September 1993 -

Cover Story

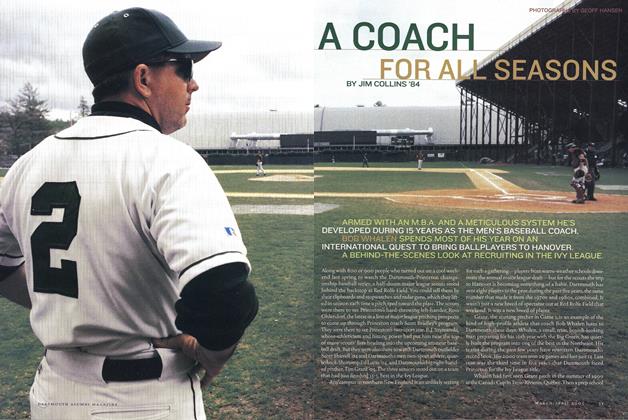

Cover StoryA Coach For All Seasons

Mar/Apr 2005 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureSome Faults, Some Solid Achievements

November 1975 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureThe Affirming Flame

May/June 2003 By SUSAN DENTZER ’77