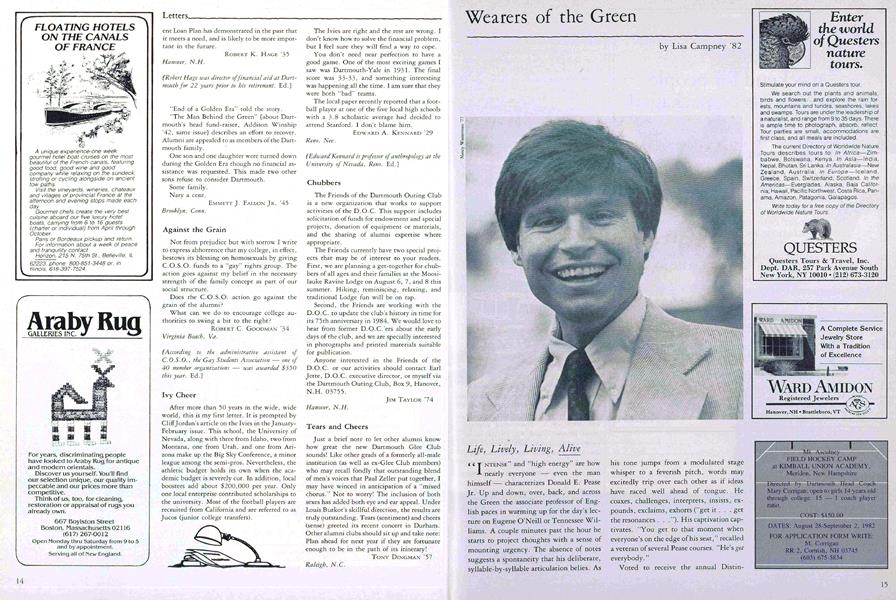

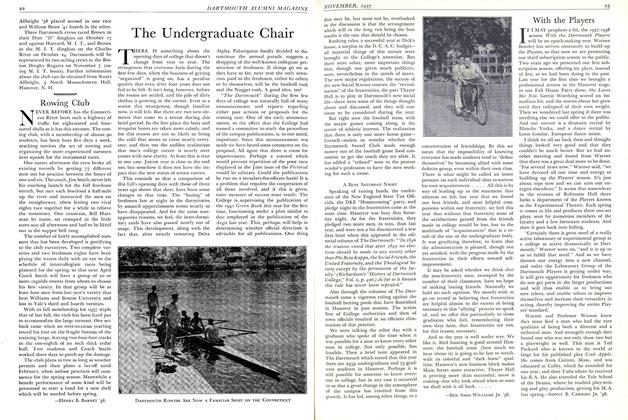

"Intense" and "high energy" are how nearly everyone even the man himself characterizes Donald E. Pease Jr. Up and down, over, back, and across the Green the associate professor of English paces in warming up for the day's lecture on Eugene O'Neill or Tennessee Williams. A couple minutes past the hour he starts to project thoughts with a sense of mounting urgency. The absence of notes suggests a spontaneity that his deliberate, syllable-by-syllable articulation belies. As his tone jumps from a modulated stage whisper to a feverish pitch, words may excitedly trip over each other as if ideas have raced well ahead of tongue. He coaxes, challenges, interprets, insists, expounds, exclaims, exhorts ("get it. . . get the resonances . . His captivation captivates. "You get to that moment when everyone's on the edge of his seat," recalled a veteran of several Pease courses. "He's got everybody."

Voted to receive the annual Distinguished Teaching Award by the senior class last spring, Pease could point to the standing-room-only enrollments in his classes to vouch for his success in conveying his literary passions to an audience "For him the literature is an emotional thing," noted Amy Lederer 'B2, who recently completed an honors thesis under Pease's tutelage. "He wants you to feel as well as think." Added Dave Vaughn '82, "He's in a different world when he's up there lecturing, and he brings each student into it one-on-one."

Yet, a Pease performance compels attention for its intellectual intricacies as much as for its outward dynamics. In analyzing a given novel or play, he searches for an organizing structure "flexible enough to make a whole series of insights possible to make visible all the tensions, contradictions, and energies." He can take material "that otherwise seems unfathomable and demystify it," commented English major Heather Guild 'B2, yet the rapid twists and turns in his path through it can also leave note-takers frustrated and lost.

"I think he expects everyone to rise to his level, in a complimentary way, as if to say 'you can do it,' " explained Lederer. He makes you work to your full potential. You're working just listening to him!

Pease frequently approaches themes m both his American fiction and drams courses by invoking writers' psychological and biographical profiles in addition to the broader historical contexts in which the} wrote. Arthur Miller's After the Fall, for example, becomes suddenly more tenable and meaningful in light of his relationship with actress Marilyn Monroe and against the backdrop of the Holocaust. While many scholars take exception to this method Pease's students call it "helpful," "refreshing," and "sometimes almost essential." Pease himself defends it: "There is a relation between the work of art an author has made of his life and what he transforms into a work of art. I want students to enter into relation with a living work. If 1 ask them to create out of their experience, to transform their experience into work, and at the same time treat [an author's creation] as though it were isolated from his experience, then I'm cultivating a contradiction, and not a fruitful one."

After earning his master's and doctoral degrees at the University of Chicago, Pease came directly to Dartmouth in 1973. Since then, in the appraisal of senior colleague Harold Bond '42, "he has grown into one of our truly outstanding teachers, with a profound commitment to literature and its humanizing values." Literature was not, however, Pease's first and only love. As an undergraduate at the University of Missouri, he followed a pre-med curriculum with a bent toward psychoanalysis before switching disciplines. A specific virtue of American literature in particular, he believes now, lies in its lack of "protection" by tradition. In contrast with its English counterpart, "American literature has no canon yet. You discover your own capacities to make it understandable and make life understandable through it. It has a whole 'New World' vision."

Despite the quanta of energy he expends in teaching, Pease said the "act of awakening the deepest senses a human being is capable of " revitalizes rather than drains him. There is real joy, he affirmed, in knowing you can share the depth and power of a writer's perceptions with your students Pease, too, demonstrates a genuine concern for his students through his own dedication. He accommodates all who wish to consult him with almost limitless office hours the week before a paper duejate, and mid-term finds him reading and scrawling lengthy marks on each of 180 finished products.

Pease's own research also reflects his rescation to make demands on himself at jeast as rigorous as those he asks of his students. "If I'm producing scholarship, then I don't feel any hesitation in asking students to write for me." With his first book, The Legitimation Crisis in Americanliterature, at the publisher's, he is currently completing a second, on novelist Thomas Pynchon, as well as studying the relation between authority and invention in 19-century literature. Scholarship in general, Pease feels, serves a critical function vis-a-vis teaching. "In research you constantly put yourself in the position to renew your powers to teach. Research alone or teaching alone can be a disease of the academic world. It's not that publishing validates a teacher it makes teaching possible."

He sees the College specifically as an environment benefitting both superior teaching and scholarship; his enthusiasm for Dartmouth would rival that of the most spirited alumnus. "I can't think of a more exciting place to be right now," he says. "There's a sense of tradition of place and to teach here is to follow in a tradition of great teachers." As for Dartmouth undergraduates, Pease decries certain stereotypes but also draws an approving distinction between students here and those he has known elsewhere. Here, "they are not intellectuals but very intelligent students." Instead of gearing themselves to purely intellectual interests at the cost of other pursuits, "they convert what they learn into action, make learning live-ly, "live, rather than sequester it. They treat education as an adventure of the mind.

Maintaining that students can always extract more from a topic than he can cover in lecture, Pease consciously tries to spur that independent thinking. His enthusifor their novel ideas matches theirs for his. For. as one disciple said, "When I read I keep thinking, 'I wonder what Pease is going to say about this.'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lovinses and the Soft-Energy Path

June 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureMAIN STREET

June 1982 By Nancy Wasserman -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWarming up for 50 years: The yeast of elderly innocence

June 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

June 1982 By Adrian A. Walser -

Sports

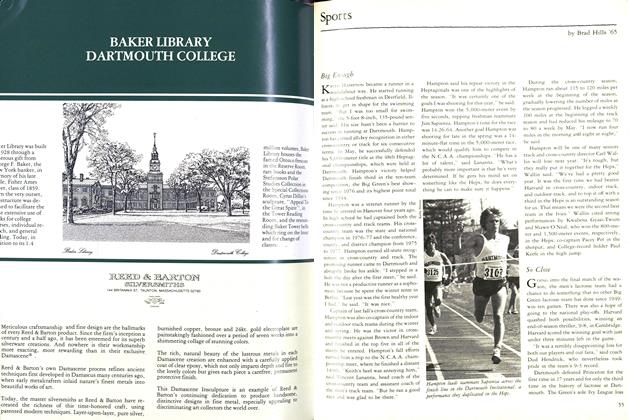

SportsBig Enough

June 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

June 1982 By Francis R. Drury Jr.

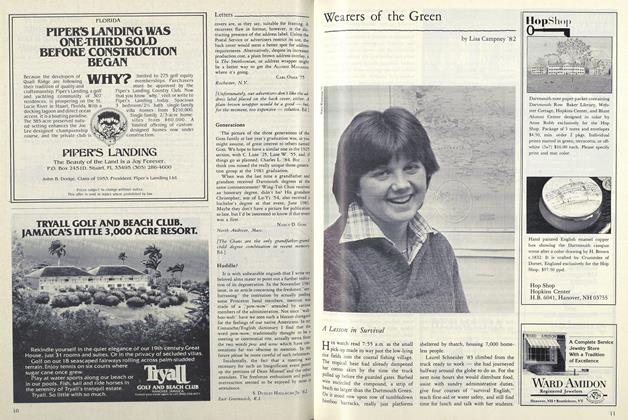

Lisa Campney '82

-

Article

ArticleThe Start of Something

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleTangible, Resilient, Ubiquitous

NOVEMBER 1981 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleA Lesson in Survival

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleRound and Round It Goes

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleSaturday Night Conscious

APRIL 1982 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleSeason of the Plague

JUNE 1982 By Lisa Campney '82