WORD-ASSOCIATION games have never been my forte, but one cue, "fall term at Dartmouth," does conjure up a number of responses: football, foliage, . . . freshmen. The latter image without doubt deserves the closest attention, for the "pea green" experience is an aspect of Dartmouth shared by all students and alumni. My recollection of it motivated me to become an undergraduate adviser.

Ego-gratification aside, I think the advisers (a.k.a. UGAs, yugas, and oogas) can positively affect "their" freshmen's adjustments to life on the Hanover plain. Contrary to the hackneyed snicker that freshmen can be spotted a mile away, they do not belong to a species separate from fellow campus-dwellers. They are, however, undergoing a transition, a period too often unacknowledged as pressure-laden and difficult. Herein lies the undergraduate advisers' niche.

In short, the UGA is one of 75 upperclassmen enrolled for consecutive fallwinter terms and selected from an applicant pool by a Freshman Office interviewing committee. Over the summer each receives an assignment of, on the average, 14 advisees billeted in his or her dormitory. All participate in a weekend-long training session prior to the start of Freshman Week. Then come group meetings with advisees to discuss topics ranging from placement tests to exclusion from fraternities, and thus begins the advisers' formal role as liaison between the incoming class and the Freshman Office, a bond maintained in varying degrees until spring.

In truth, this factual but sterile outline of an UGA communicates the essence of neither the person nor the function. That can be better accomplished by less prescriptive facets of the adviser-advisee relationship, the "little things" like celebrating a birthday or studying for an exam together. Several of my "UGees" later told me that letters I wrote to them the summer before they arrived at school helped lessen their nervousness. Small but meaningful touches like these can spark friendships that will endure.

Time is a key factor in both the freshman experience and the undergraduate adviser's role. It takes time to appreciate Dartmouth wholly for what it now is and not for what it seemed to be, or ought to be, or was. It takes time to develop the ideas and impressions that germinate during those first days and weeks in Hanover, and more time to amend the hasty and inaccurate ones. Finally, it takes time to acquire trust and confidence in new people, such as advisers, and time for those people to demonstrate that they merit that trust.

Ideally, perhaps the conception of an UGA as a caring, level-headed, and trustworthy individual eventually will be implicit in the title. For now, UGAs should remember that they alone, from Freshman Week onward, can nurture this image. They are founding a tradition, and their performance will reflect on their successors as the three-year-old advising program continues to develop. Conversely, UGAs must answer for any discredit to the program. To cite an extreme example, one UGA allegedly "advised" her freshmen, at one of their first meetings, with all her gripes and complaints about Dartmouth what a welcome! Of course, the screening process tries to eliminate such irresponsible adviser candidates in favor of better qualified peers, but it cannot guarantee infallibility.

Sincere and persistent effort, effort which some advisers (though I would hope only a few) will not expend steadily, will help adviser-advisee friendships to evolve after the onset of fall term. Sometimes UGAs find themselves treading thin lines to play fair and avoid favoritism, to provide help but not divulge confidences. Bits of probing may effectively pierce shyness barriers. Most important, UGAs can offer patient encouragement and be sensitive to confusion and disillusion, to homesickness and academic struggles, to things freshmen will mock in retrospect, and other concerns that may occasionally require more serious attention. Some freshmen need only the invitation of an open door, but more frequently UGAs must knock on theirs.

On a darker note, nothing frustrates and disheartens an adviser more than learning that freshmen have kept troubling problems to themselves. One young man I met left Dartmouth after a term, and it bothered me to discover that neither his UGA nor many friends seemed aware of his decision to transfer. Intentional rebuffs, though, sting the sharpest: freshmen who choose to ignore their UGAs, who resent their "interference" and "meddling," who simply do not like or trust them, who refuse to confront and share their anxiety. In such cases, advisers may just have to accept their feelings of rejection and ineffectualness. Their doors might as well be sealed tight if the thresholds are never crossed.

However much we analyze the UGA program and its value on a theoretical plane, we find its crux to be day-to-day, one-on-one interactions. Satisfaction from them rewards an UGA well. I'm sure I'll miss advising this year; I made friends with some special people Dartmouth freshmen. I mean, sophomores and juniors.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

September 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryInauguration of the 14th President: The Spirit of Eleazar Wheelock ... Transmitted through his Successors'

September 1981 -

Feature

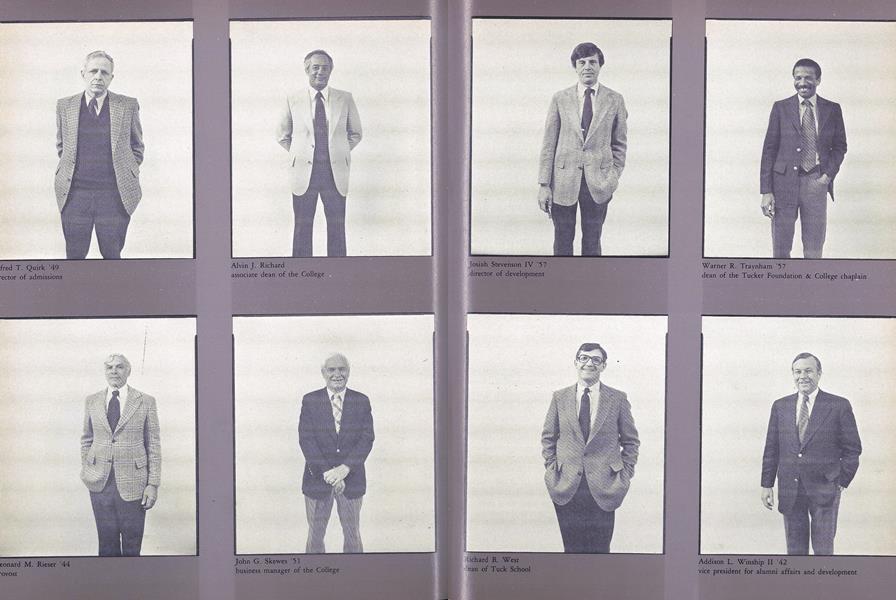

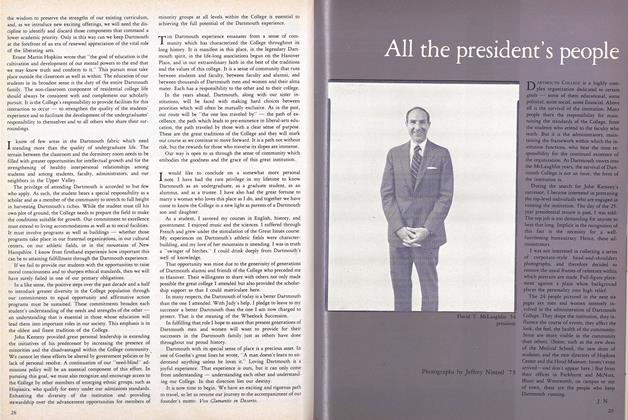

FeatureAll the Presidents's People

September 1981 By J. N. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

September 1981 By Clement B. Malin -

Article

ArticleHistory Without Battles

September 1981 By Beth Ann Baron '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

September 1981 By Jacques Harlow

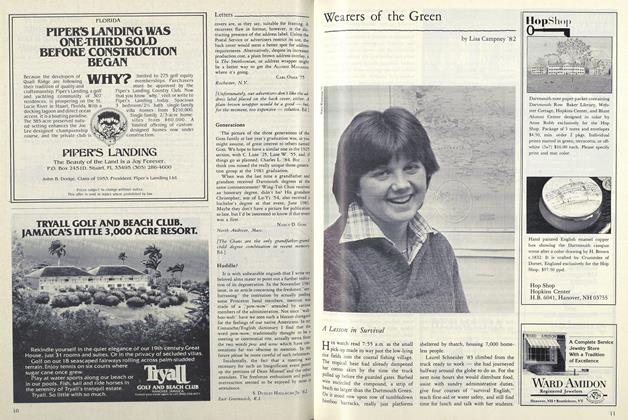

Lisa Campney '82

-

Article

ArticleTangible, Resilient, Ubiquitous

NOVEMBER 1981 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleA Lesson in Survival

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleRound and Round It Goes

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleSaturday Night Conscious

APRIL 1982 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleLife, Lively, Living, Alive

JUNE 1982 By Lisa Campney '82 -

Article

ArticleSeason of the Plague

JUNE 1982 By Lisa Campney '82

Article

-

Article

ArticleSchools Change Names

March 1942 -

Article

ArticleValedictory to All-Star Class Agents

January 1943 -

Article

ArticleThe Votes Are In

Jan/Feb 2007 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

APRIL 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleClass of 2002

July/August 2008 By Lauren Smith '08 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's 175 Years

January 1945 By New York Sun.