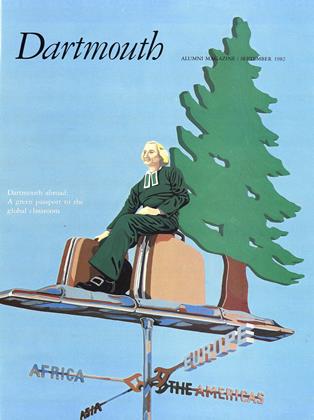

THOUGH hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Dartmouth students past and present have begun stories with the words "While I was on L.S.A. . . , " those that follow can turn the tale in innumerable directions. I was one of some 20 Dartmouth students and a professor who journeyed with common cause to Puebla, Mexico, this past spring, but our different backgrounds, assumptions, and interests made the ten-week stay both a group and personal experience. I suspect each of us would recount it differently. And the number of stories multiply in another way few would be content telling only one experience from our language-study program.

From the first, as two faltering speakers of Spanish (one with an absurd French accent) wandered about the Mexico City bus station, to the last, as almost-fluent speakers (one still with that accent) confidently revised airline reservations, our days were filled with sun, fun, and more than a little learning. Besides 20 class-hours each week, we did our homework as we lived with Mexican families and tried to cope with an unfamiliar language and culture. For recreation, we swam, tanned, played basketball, emptied bottle after little pink bottle for stomach upset, got lost on flyfilled buses, and talked to each other of our days long into the night, be it over freshly squeezed fruit juice or bottles of tequila. More than once, Dartmouth South ran amuck in Mexico City and Acapulco, always on the prowl for good pizza and cold beer.

Yet this "While I was on L.S.A. . . story is not to be one of staggering gringos in the Zona Rosa or of grinning Big Greeners yukking it up on some new adventure. Those recollections, often the first that come to mind, obscure the fact that the program was also a time of deep personal reflection. Perhaps the transplanted Americans (and one Canadian, as he was so fond of reminding us) thought deep thoughts because we wanted to or because we were used to doing so, but I believe many of us reconsidered our circumstances because we felt forced to pushed by a powerful contrast.

You see, our spring in sunny Mexico turned out to be anything but a glossy vacation package. When not on the beaches, we lived among a misery and a wretchedness of the human condition that (for most of us) had been locked behind the smudged glass of a commuter train window or television set. This desperation was everywhere: with the corrupt policemen, among the devout churchgoers, and shadowing the street people. Especially the street people, whom I remember most vividly. As Dartmouth South walked across the park, we often saw a dirty beggar, his clothes barely strung about his fly-covered frame. On the way to class, we saw halfmen who pushed themselves around the streets on low carts as their useless, toothpick-thin legs dangled in the dirt. Many whole men, too, walked like cripples, as a bottle clutched in work-worn hands gave no direction.

For me, the miserable ones became something of an obsession, and I struggled to talk with such people. One, Ana, a domestic servant, even became a friend of mine. She was better off than many in her land, for her employers provided her with stale food and a one-room roof-top shack. Yet for all the conversations I had with Ana, I can't honestly say that I know her. Perhaps, and I do not mean to be savage, there was little about her to know besides her work, that is. She had no way of smiling, no personality traits, no mannerisms particular to her that I recall. She cleaned, she cooked, and she lived for others. Yet these others were not family or friends she had none of those. They were her employers.

There, in the midst of what one of us termed "L.S.A. Hell," these experiences brought me back to Dartmouth and to a long-forgotten admonition. In Hanover, as in so many places, the young are told that the privilege of education carries with it a heavy responsibility: the need to make a "positive impact" upon society. Yet before my stay in Mexico, I heard the voice of conscience only weakly, beneath the din of course changes, enrollment patterns, friends, future plans, and matters such as these. During the ten weeks I spent on a rarely traveled road, the moral challenge gained new meaning. I tossed coins and smuggled food, doing what I could to ease a troubled conscience and to help my brothers and sisters.

Now the admonition's power wanes. I sense that the vitally important memories are moving behind a distant, foggy mirror as I return to more worn paths. I feel the urge rising within me to take another look at an activity-laden resume and a (dare I say adequate?) grade transcript. I fear that the misery of Ana and her people appears not to be a momentous enough matter to arouse my sustained action. In theory, accepting such responsibility is what cuts to the heart of the famed "Dartmouth Experience." I only wish it were closer to the reality.

Steve Farnsworth is one of this year's undergraduate editors and Campbell Interns. He is anative of Vergennes, Vermont, and an international relations-government major. Presentlyeditorial page editor of The Dartmouth, he isalso a sometime saxophone player in the Dartmouth College Marching Band.The Campbell Internship was established inmemory of Whitney Campbell '25 by his classmate Robert Borwell to provide undergraduateswith experience in journalism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

September 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

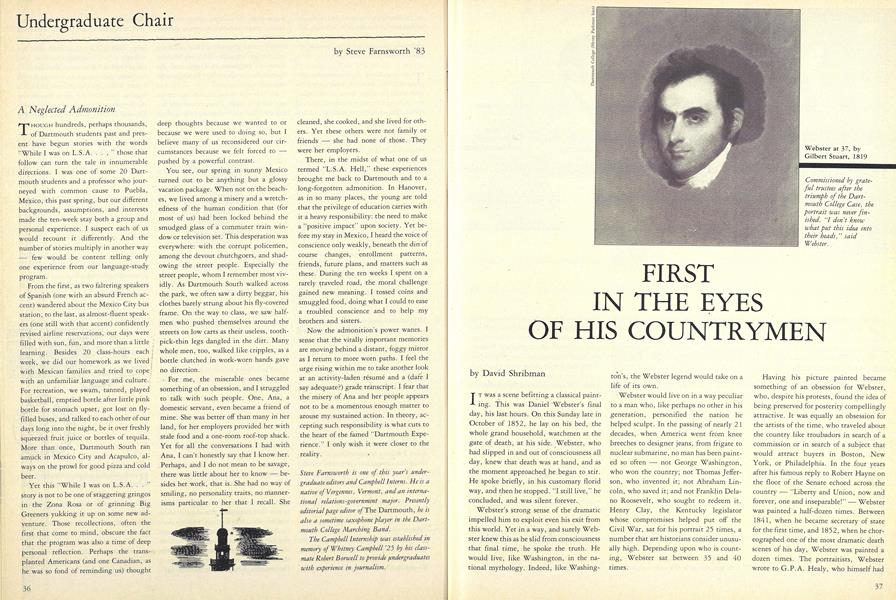

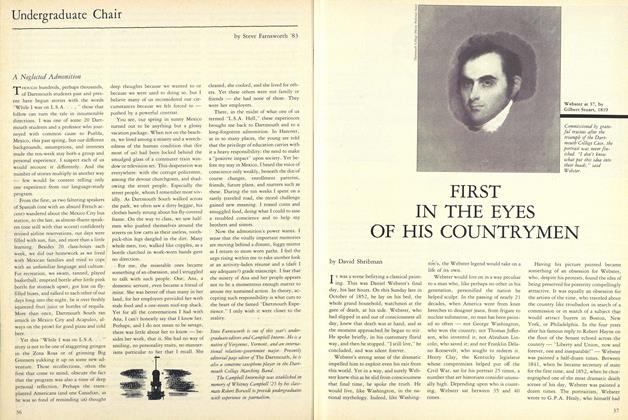

FeatureFIRST IN THE EYES OF HIS COUNTRYMEN

September 1982 By David Shribman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

September 1982 By Daniel M. Searby -

Article

Article"Man Better Man"

September 1982 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

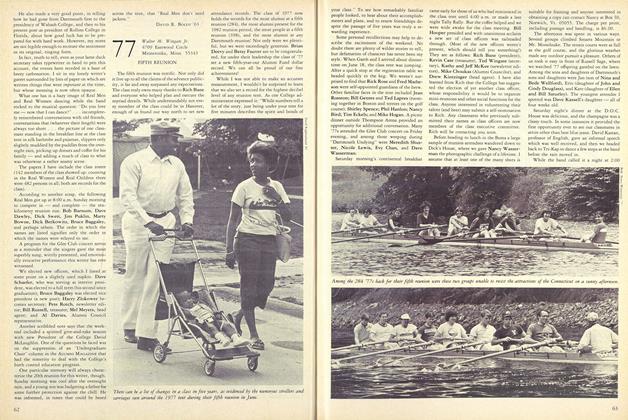

SportsHelp Wanted: Rising Sophomores

September 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1977

September 1982 By Walter M. Wingate Jr., Lindsay Larrabee Greimann '77

Steve Farnsworth '83

-

Article

ArticleThe Class of Nodding Acquaintances

November 1982 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleSenior hockey: through the golden years on silver blades

November 1982 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleThe Great White Cold

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleRhodes Scholar

APRIL 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleSanford Gottlieb '46: "An American pacifist leader"

APRIL 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Article

ArticleFormer "Wearer of the Green" now sports black and white

OCTOBER, 1908 By Steve Farnsworth '83