"WHAT are you interested in beside theater?"

When this question was put to Errol Hill, Willard Professor of Drama and Oratory, he dropped his head to one side, thought a minute and replied, his dark eyes dancing behind horn-rimmed glasses: "What else is there?"

Errol Hill is a hundred-percenter. He has produced and directed over 150 plays and performed over 40 major roles in the U.S., West Indies, Nigeria, and England. He has taught theater at the University of the West Indies, the University of British Columbia, University of Ibadan, City University of New York, Leeds University in England, and the University of California at San Diego.

Henry Williams, professor emeritus and grand panjandrum of drama at Dartmouth, says, "When John Finch hired Errol in 1968 he was choosing better than he knew. The English Department wanted Errol, but we got him because he believes you only learn theater by producing plays. He is that rara avis, a brilliant scholar who is also a gifted teacher. He can teach playwriting, acting, directing, and theater history because he himself is an actor, playwright, director, and student of drama. He is undoubtedly the world's leading authority on Caribbean drama."

Students hold Hill in awe. Actor Phillips Kaufmann '82 comments: "What is often admired by students is the slick, the pop, the constantly trying to be with it. Errol Hill never stoops to that. He is dignified some say aloof— but behind the formality there is great warmth. He imbues everything he does with importance. He's patient and even-tempered. I've never seen him angry, but I wouldn't want to be in the path of his wrath when he encountered dishonesty or cruelty. His integrity is unquestionable."

Hill's comic folk opera Man Better Man, which was presented Off Broadway by the Negro Ensemble Theatre, is about the stick fighters of his native Trinidad who are anointed by an Obeah Man (witch doctor) with"man better man," a magic weed that makes them invincible. Anyone contemplating Hill's charmed life might conclude he, too, was anointed with 'man better man."

One of ten children born in Port-of-Spain to a father who was an accountant and part-time preacher and a mother who was the pillar of the Methodist Church, he remembers the Sundays of his youth with a shudder. "We were dragged to church at 5:00 a.m. At 9:00 came the regular service. Then leader's meeting, to discuss how scripture affected our lives. Then Sunday School. At 4:00, Methodist Sunday School. At 7:00, Matins. It cured me of church. The whole ordeal was redeemed by only one thing church plays. My mother took the leading roles. She had the most beautiful speaking and singing voice I ever knew. I acted in my first play, Man in theStreet, when I was about 15."

In 1949, Hill won a prestigous British Council Scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London. "England was a big change from Trinidad," he recalls. "It took six months before I liked it. I worked as an actor and announcer on the BBC and landed a few parts in plays, not easy because British directors were more concerned with skin color than acting ability. I also toured the provinces as stage director of an Arts Council troupe very educational."

After receiving a graduate diploma, with distinction, from the Royal Academy and a diploma in dramatic art from London University, he returned to the West Indies and taught drama and the arts at the university for six years.

In 1958, Hill won a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship to Yale and made his first journey to the U.S.A. He accomplished a feat that should go down in Yale's annals of education: essentially, earning three degrees in four years. He completed work for the master of fine arts at the School of Drama as a special student, but could not receive it because he had no B.A. Backtracking for two years to satisfy undergraduate requirements, he entered a doctoral program after the first year. By 1962, he had two degrees in hand and had completed course work for the doctorate, which was actually awarded in 1966. His dissertation was later published in a stunning book, The Trinidad Carnival, Mandate for a National Theater.

The most enthusiastic applauder at Errol Hill's epic commencement from Yale was Grace Hope Hill, a statuesque Barbadian whom he had married five years earlier. They met in England where she was studying at Bedford College of Physical Education. Grace, whose name is a perfect eponym, has taught dance and physical fitness for over 25 years and her book/ca-sette Fitness First received international recognition. Professor Emeritus Harry Schultz states correctly: "It would be a misrepresentation to present Errol sans Grace. It is the husband-and-wife who are the most impressive of all. Together they have made a great difference at this college."

Dartmouth degrees are piling up in the Hill Family: Errol honorary M.A. '73; Grace — M.A. '76; Da'aga, now at University of Virginia Law School, '79; Aaron, a sophomore. The Hill twins went further afield, Claudia graduating from Colgate and Melina from Brown Ivy Leaguers and athletes all.

It is lucky the Hills' Dartmouth connection tion is strong because Errol Hill receives many tempting offers. "There was a huge hunt for black professors in the early seventies but there was no way I'd leave this place," he says. "Our children have flourished here. Oh, occasionally a racial incident came up at the school, and sometimes I long for a snowless winter, but Hanover is home."

In 1973, President Kemeny persuaded Hill, the first black to gain tenure at Dartmouth, to become the College's first affirmative action officer. Although he has grown up in a very different tradition, Hill's courtliness and courtesy impressed the racial minorities whose cause he espoused. ("He had the grace of a prince and the patience of a monk," recalls a student from Harlem.) "Taking that job was a major self-sacrifice on Errol's part," President Kemeny said recently. "It was hard and frustrating, and the fact that he was willing to do it demonstrated enormous loyalty to the institution. He was superb. He set up the ground rules, got everything running smoothly, and after a year and a half recruited Margaret Bonz to take over. He was just excellent at it."

Honors keep coming for Errol Hill. An honorary member of Phi Betta Kappa, he was just elected president of the Dartmouth chapter. The government of Trinidad gave him a gold medal for his work in drama. He was cited by the New England Theatre Conference for his teaching and scholarship. He lectures on Shakespeare for the Folger Library and on black theater in three continents, and next year he will hold a Chancellor's Distinguished Professorship at Berkeley.

If, as Socrates said, real power lies in your ability to do what you want, Errol Hill is a powerhouse. His self-discipline is awesome. He works 14 hours a day, 8 days a week. "I'm not a workaholic," he says. "There just happens to be so much to do and not enough lifetimes" (which is a fair description of a workaholic). "I'll finish my history of Jamaican theater during my sabbatical this year. My ambition now is to complete my history of black theater in America. It will take five years. My greatest need is graduate students to help with research; so far I've been doing it on my own."

It is a good bet that history of black theater will be achieved for unlike his hero Hamlet when Errol Hill says, "This thing's to do," he does it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

September 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

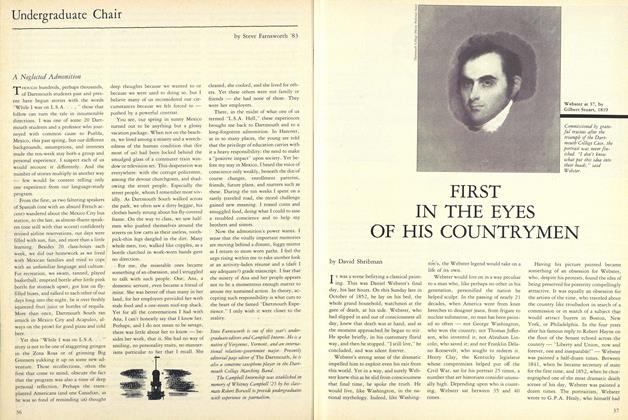

FeatureFIRST IN THE EYES OF HIS COUNTRYMEN

September 1982 By David Shribman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

September 1982 By Daniel M. Searby -

Sports

SportsHelp Wanted: Rising Sophomores

September 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

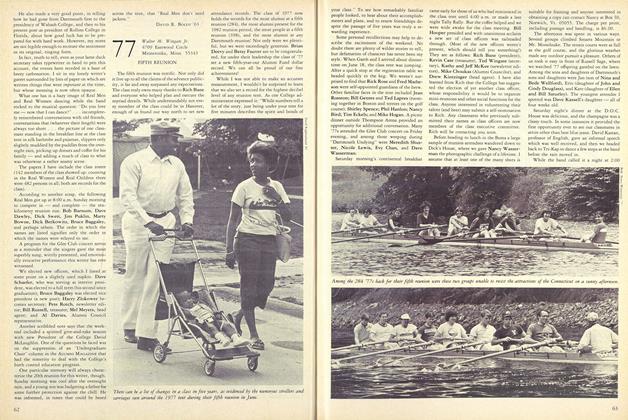

Class Notes1977

September 1982 By Walter M. Wingate Jr., Lindsay Larrabee Greimann '77 -

Class Notes

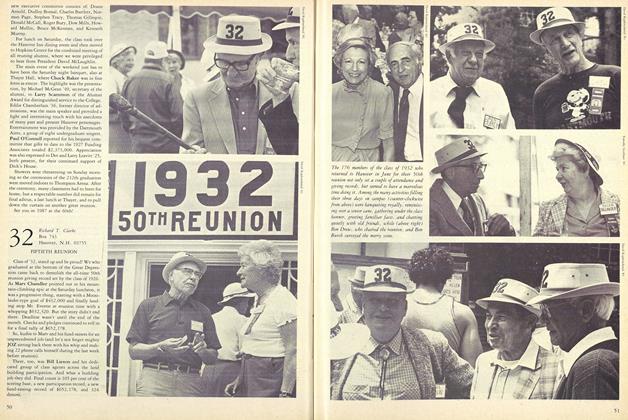

Class Notes1932

September 1982 By Richard T. Clarke

Nardi Reeder Campion

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to Editor

September 1979 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

March 1980 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

FEBRUARY 1989 -

Article

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

MARCH 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

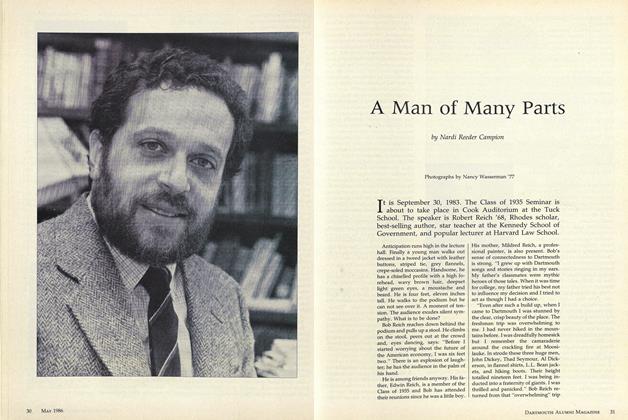

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

MAY 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion