My name is Monica andl am a former White House intern.

Okay, not that Monica. But Monica Lewinsky and I share first names. We both worked in a sensitive White House office in the West Wing for several months, and either know or knew of several people now being discussed in the newspapers.

Like Monica

Lewinsky, I too as an intern once had a bird's-eye-view of the Presidency. My experience was both extraordinary and unexceptional. It was extraordinary in a basic sense because I am an immigrant's daughter, from an indistinguishably middleclass family with no political connections, who based on the strength of my academic and extracurricular record at Dartmouth was brought into the White House to work for six months alongside some of the most powerful men and women in America.

It was extraordinary in an educational sense because I learned what kinds of papers needed to be faxed and filed and delivered daily for individuals making decisions affecting every person in our country.

And it was extraordinary in a personal sense because I assisted several public servants, both political appointees and civil servants, who day in and day out went about their routines displaying the utmost professionalism.

It was unexceptional because my experience was not the stuff of headlines. I have no scandalous stories to tell.

For the sake of the staff members I worked with and the integrity of my service in the White House, I want to believe in the President's innocence. For the sake of our country, I want to be able to say to my Irish friends, and also my British and Slovakian and Japanese and South African and Greek friends here in Oxford, that the allegations against him are untrue. On the other hand, I know that the investigators have a right indeed a duty to find answers to the questions now before them.

What are the facts? We, as Americans, cannot be true to ourselves until we know where our government stands. Truth is paramount. So is wisdom in knowing where and how best to find it. The frenzy with which this storyhas gathered momentum and overwhelmed our public consciousness disturbs me. Given the gravity of these allegations, we must now, more than ever, exercise prudence and restraint. We need to examine this matter thoroughly, in the right way, the first time.

Why? Because the means we employ today are part of the end consequences that lie ahead. It is not just President Clinton, the man, or the Clinton administration, or even the Democratic Party that currently hangs in the balance. It is the institution of the American Presidency.

The world is watching. As the leader of our nation, the President is our chief representative. Who he is ultimately reflects back on us. As Americans, therefore, the outcome concerns us all. The American chief executive differs from his European counterparts in one fundamental way. He is not only head of the government (a partisan figure), but also the head of state (a national figure). Unlike the British prime minister or the German chancellor, the President of the United States fills two roles at once: he stands in the midst of politics, and he stands above politics.

The President is not just the leader of the executive branch or of the Democratic Party. In his highest calling the President is the leader of the nation as a whole. That makes him the chief representative and guardian of our country's national unity.

My name is Monica and I am a former White House intern. And I am uneasy.

'96 class secretary, is studying toward a Ph.D. at Oxford. This essay is adapted from a column she wrote for The. Boston Globe.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

April 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureSpiked Boots and the End of an Era

April 1998 By Edie Clark -

Feature

FeatureA Change in the Weather

April 1998 -

Feature

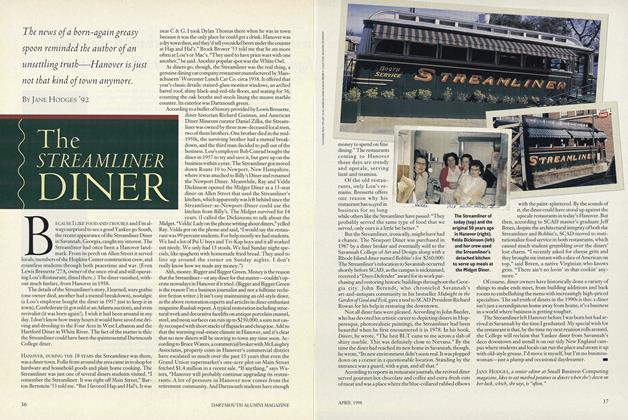

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

April 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleThe Benefits of a College Town

April 1998 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

April 1998 By John MacManus

Article

-

Article

ArticlePLAYERS PLAN SEVEN SHOWS

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

JAN./FEB. 1980 -

Article

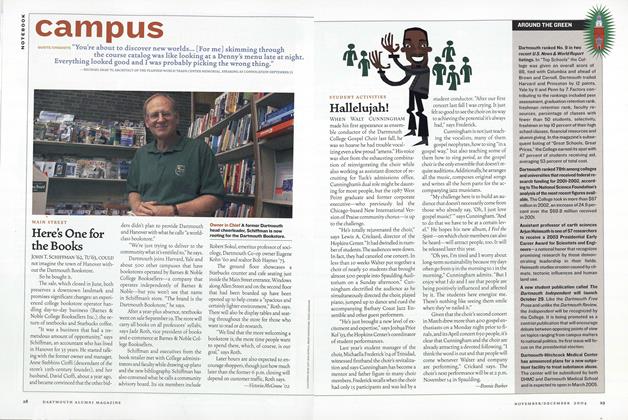

ArticleAROUND THE GREEN

Nov/Dec 2004 -

Article

ArticleSexagenarian Hiker Travels Light on the Appalachian Trail

OCTOBER 1982 By D.C.G -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

January 1940 By Edward Fritz '40 -

Article

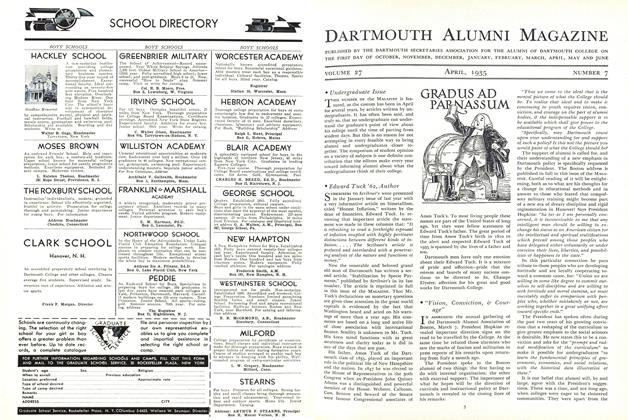

ArticleEdward Tuck '62, Author

April1935 By The Editors