The exodus of College faculty to private secondary schools

It was something of a revelation. He strolled the grounds, poked his head into a classroom or two, nosed around the dormitories. He paused for a tranquil moment in the art gallery, paced the athletic fields, looked about the library. This was, to be sure, a different world, an alien world really, a world away from Xenia High School and the muted timbre of his own high school days in a small town in Ohio. And yet the thought kept returning ;to Donald W. McNemar: There was something about Phillips Andoer Academy that appealed to him, that appealed to his sense of community, that appealed, most surprisingly of all, to his sense of democracy.

"I grew up in the Populist Midwest," he was saying during another stroll on the campus, more than a year later, "and I had doubts that I wanted to spend my life with the children of affluent families. But that was a stereotype, and I came to realize that this school had a real commitment to democracy, to getting students from diverse backgrounds, and above all, to a good education."

In the end, of course, he took it. He gave up his tenured position on the Dartmouth faculty, he resigned his position as associate dean of the faculty for the social studies, and he accepted the offer to replace Theodore R. Sizer as headmaster of Phillips Academy.

That decision, to relinquish a position at the commanding heights of higher education and to accept, in its stead, a job at the secondary-school level, surprised many of his friends and colleagues. Some actually were troubled: This was, they suggested, usually in hushed voices and with knowing glances, against the natural order of things.

But difficult as his decision was, Donald McNemar was not a pioneer, not a lone figure sailing against the wind of that most hidebound of professions, education. In recent years, in fact, a growing number of educators have chosen to leave the ranks of the colleges and universities to lead preparatory schools, and Dartmouth has emerged as a leading contributor to this quiet revolution.

"Dartmouth people," says Thomas M. Mikula, former director of the A Better Chance Program at Dartmouth and currently the headmaster of Kimball Union Academy, "are running some of the largest, and best, secondary schools in the country."

Since early in the last decade, Charles F. Dey '52, the associate dean of the College and dean of the Tucker Foundation, be- came the leader of Choate Rosemary Hall in Wallingford, Conn.; Mikula moved from the Tucker Foundation to Kimball Union, in Meriden, N.H.; John William Ragle left his position as director of the Master of Arts in Education program to become headmaster of Governor Dummer Academy in Byfield, Mass., and Richard P. Unsworth, another past dean of the Tucker Foundation, became the headmaster of the Northfieid Mount Hermon School in East Northfieid, Mass. A year after McNemar moved south to Andover, Ralph N. Manuel '5B, dean of the College, became the superintendent of Culver Military Academy and the Culver Girls Academy in Culver, Ind.

To the classrooms and playing fields of these independent schools, as they prefer to be called in this era of democracy, this very special group of former Dartmouth administrators are taking more than a whiff of the college experience. Their colleagues say that they are bringing more, even, than what Manuel calls an "ideal of service" or what Dey calls an "intuitive sense" of the needs of young men and women. "Kids used to approach crossroads in their lives, but today they approach cloverleafs," says Burge Ayres, a former dean of Choate and still a familiar figure on the school's campus. ''College administrators have copped out on the teaching of values. If anyone's doing that, it's being done on this level. Charlie Dey doesn't have a job here; it is a mission."

On the surface, of course, this mission does not differ substantially from the roles this group played on the Hanover campus. They remain educators, curators, it might be said, of a new generation of young people; on both the secondary and college levels, the emphasis remains on learning, in all its variegated and sometimes bewildering forms. But at secondary-level boarding schools, where many of the students are away from home for their first time, the learning is more intense and the teaching is more intimate.

That, it turns out, is part of the allure of the private school. "Someone arrives here at age 13, not yet an adult, and leaves at 18, very much a person," says McNemar. "That change can be drastic. In college, people choose majors. Here, in their adolescent years, they are becoming persons. I see the two as entirely different things. Here there's a much greater range than there is in the college years."

In many ways, several of these headmasters agree, the secondary years are more critical than the college years. They agree, moreover, that their experience as teachers and officials at Dartmouth has served to reinforce that belief. Dey, for example, speaks of his gradual realization that "people who didn't come through adolescence in good shape might not pull through for the long haul," adding: "If they haven't developed a reasonably good self-image, some reasonable goals for themselves, and haven't begun to take some responsibility for their own education, there will be trouble ahead."

Dey cites his own odyssey through the education system. As a dean at Dartmouth, he became aware of more than simply the importance of solid secondary-level preparation; he came to see how the increasing complexity of contemporary life enhanced, rather than diminished, the importance of secondary preparation. "Life is totally different for kids of this generation, he says. "You. can have sex, easy access to alcohol or other kinds of drugs, and you feel a burden to make some sort of decisions. I felt some of these as a relatively naive freshman at Dartmouth, but, really, it was not until I joined a fraternity that I had to confront them. Kids are confronting all of these things much earlier today."

He also came to see that education, like much else in the wider society, was becoming increasingly specialized, and that troubled him. "People at Dartmouth were interested in engaging people in their particular areas of expertise, be it organic chemistry or football," says Dey, who is 52 years old. "I wanted to see education whole, to be in an environment where the educators were committed to the student m all areas of his or her life."

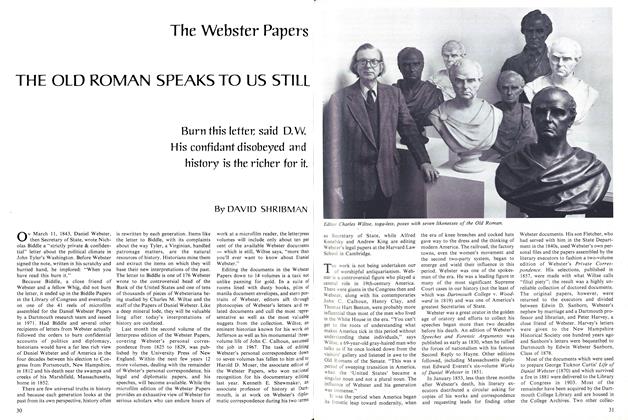

The word "preparation" is at the heart of the philosophy that Dey has developed at the leafy campus of Choate Rosemary Hall. My objective," he says time and again, is to give to the world thinking people, people who can express themselves and who can do so with conscience. Our job is to give to the world people who will be independent both in mind and in spirit."

Today, Dey's decision to remain at Choate Rosemary Hall, at least for the short term, is motivated in part by what he calls selfish" reasons: He likes the campus, with its Georgian buildings, its ivycovered archways, its wide expanses of playing fields, and he likes the latitude given to him as an independent school educator. "I'm drawn to the freedom of the place," he says. "We can make learning the center of what everything is all about. It can be the first priority here. I'm not saying that you can't do this in a public school, but so much is thrown to them from other people's agendas. They're called upon to do so many things that may be peripheral to the essence of education."

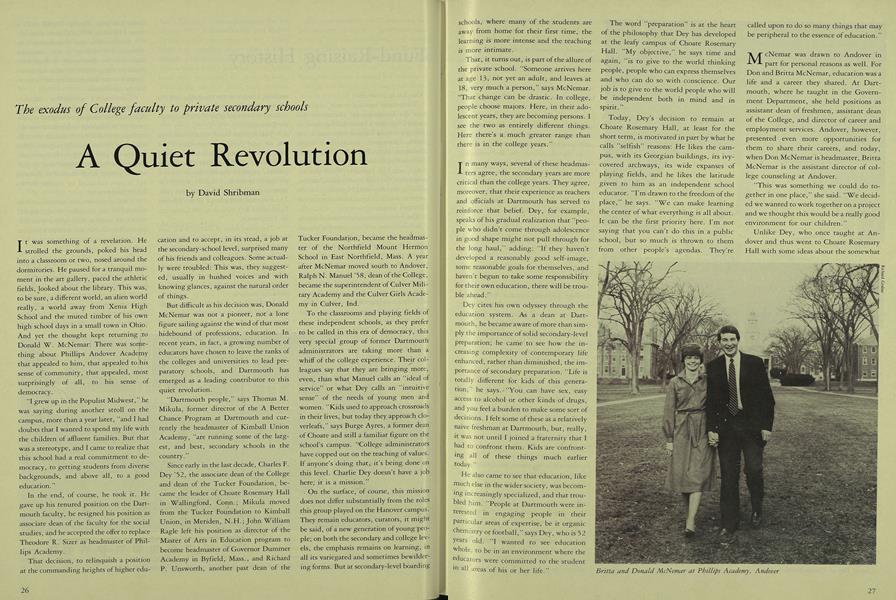

McNemar was drawn to Andover in part for personal reasons as well. For Don and Britta McNemar, education was a life and a career they shared. At Dartmouth, where he taught in the Govern- ment Department, she held positions as assistant dean of freshmen, assistant dean of the College, and director of career and employment services. Andover, however, presented even more opportunities for them to share their careers, and today, when Don McNemar is headmaster, Britta McNemar is the assistant director of college counseling at Andover.

"This was something we could do together in one place," she said. "We decided we wanted to work together on a project and we thought this would be a really good environment for our children."

Unlike Dey, who once taught at Andover and thus went to Choate Rosemary Hall with some ideas about the somewhat cloistered life of tradition-bound prepschools, the McNemars approached Andover with few expectations. They had to be persuaded that they had made the correct choice.

Before long, however, they realized that they had. "As we came to know the school and the opportunities here, it became pretty clear that this was something we wanted to do," he said. "Part of it is that you always hope that you can make a difference, whether it's in the lives of young people, or colleagues, or an institution, and this seemed to be a setting where we could contribute and could carry out our commitment to young people.

It wasn't long before McNemar found that the demands on a prep school headmaster were formidable. Besides the dayto-day administration of a school with a budget equivalent to that of many small towns in New Hampshire, there are the inevitable meetings: Wednesday's lunch with administrators, Thursday's lunch with the faculty advisory committee, Friday's breakfast with student leaders, and more. He also teaches two courses, one on global food issues and the second on African history, and he is working on the development of a high school curriculum for economics. He has abandoned, for the time being, his personal research in international relations.

"You have to have a very broad-based care for young people, because if you're interested only in your scholarly development, it's best to stay at the college or university level," says McNemar, who is 39 years old. "In this setting, you're a generalist. I teach in the classroom, I speak at school meetings, I play stickball in the spring after supper, I counsel students in disciplinary trouble. That's all part of the job, and yet the bottom line of all this is that you care about these people in all aspects of their learning and growth."

It was, perhaps above all, the sense of community that attracted the McNemars to Dartmouth, and it was the sense of community offered by Andover that lured them away from Hanover. Today they live in a rambling white house, built in the first decade of the 19th century from designs by Charles Bulfinch, on Andover's Main Street. There, in an earlier time, the American Temperance Society was founded and now, as the headmaster's house, the house is often used to gather and greet Andover students. In two senses, the school is all around them.

"We've thought a lot about the importance of community, which Dartmouth cultivates more than a lot of other colleges do, and which is very important here at Andover," says McNemar. "One of the concerns I've had here is that so many of the pressures on young people are focused on themselves. They have a me-oriented view of life. But I think people's relationships with each other are just as important. Belonging to something bigger than yourself is extremely important."

In the meantime, the McNemars believe that they have learned something themselves. They have discovered that their stereotypes of prep-school life, and of Andover, were more suited to Tom Brown'sSchool Days than to the school they lead today. "We found that this wasn't what we thought it was at all," he says. "It's sort of exciting discovering how wrong our stereotypes were, and discovering all the possibilities here."

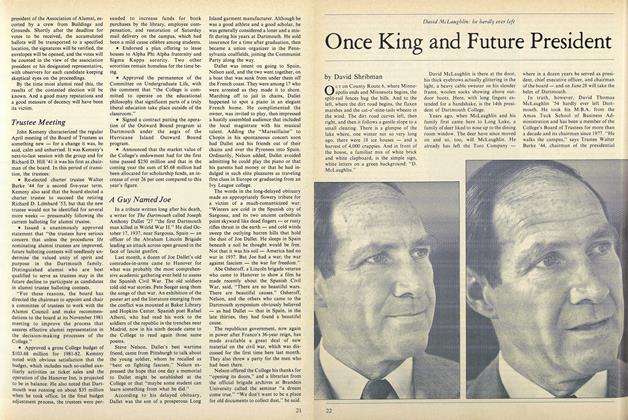

Manuel, who worked in Dartmouth s admissions office and served as dean of freshmen before becoming dean of the College, has made a similar discovery. As a young man, he knew few people who left his home town of Brunswick, Md., for a private secondary-school education. Today he remembers dinner-table discussions when family members wondered aloud why a cousin had gone off to prep school.

"I grew up thinking they were for the wealthier kids, or for the kids who couldn't cut it, either academically or socially. Or they were for the kids who were disciplinary problems. It was that foreign to our way of thinking," says Manuel, who is 46 years old. "But at Dartmouth I discovered that the kids who went to private schools had a better education than I did. They had already, read the books I was reading for the first time."

Already he has found that Culver, set on 1500 acres of hills and woodlands on Indiana's Lake Maxinkuckee, offers him the chance to set the tone for a community where, as he is fond of saying, the life of the mind is preeminent. "A preparatory school is not led. in the same way as a college or university," he says. "The person who heads a school like this is looked to for leadership, is sought out to have a vision of what the school can be, how it can achieve its potential. I think I can have a greater impact on Culver on the institution and on the students than I ever could at Dartmouth."

The opportunity to have an impact on the lives of young people is what drew Manuel to higher education, and it ultimately is what drew him to Culver and its 800 students last autumn. He grew weary of the chain of committee meetings and reports that comprised his day at Dartmouth and came to prize the chances he had to have contact with students. Now, though he occupies the top position at Culver, the students again are a part of his life.

"I can't describe how fulfilling it is to sit down with a student, at night in the dorms supervising study hours or in my office, talking to a student about who he is and who he is going to be," he says. "I guess I was cut out to do this kind of work."

Education on this level is a matter of classroom lectures but there is also a more personal level of education, more a matter of nurturing, and Manuel has found that he is comfortable in that role. "We're in the business of teaching, not just ideas but how to live," he says. "Our job is taking people apart and putting them back to- gether, so they can come away with some idea of who they are» The kids make mistakes, but they are growing. They are 14 to 18 years old, and they are bound to make mistakes. We have to understand that our job is to make certain that their mistakes are not fatal and that they learn from them."

Some of these headmasters have come to in fact, that secondary education is in many ways more important than university-level education. With the cost of private education climbing steadily a year at Culver costs more than $8,000, at Choate more than $9,100 for boarders a number of parents are choosing to send their children to private secondary schools and then on to public colleges. "A lot of our kids are going out of here to the public colleges," says Manuel. "They've gotten their private education on this level. I've heard it often. It's because parents believe a private education is more important at this level. They believe that if you have a sound basis for making morally correct decisions by the time you're a senior in high school, it will serve you the rest of vour life."

And yet these headmasters have not turned their eyes from the importance of the public school system, which still trains the vast majority of youngsters in the rudiments of the academic disciplines and in the assumptions of American life. "A democratic society can't survive on the basis of its independent schools," says Dey, himself a graduate of a public high school. "This nation has to put public education first. But I believe that education is the function of the parents, not the state, and the parents must choose the kind of education they want for their child."

For their part, however, the life at the head of a private school retains enormous appeal. "The fun," says McNemar, "is that you do everything. One minute you're dealing with a $15-million budget for the coming year and the next minute you're teaching a class, or talking to the director of the art gallery. Personally it's satisfying because it combines the teacher and administrator in a very important way. If you become a college dean or president you often move away from the students and get more and more into money and management. Here you're constantly engaged in the teacher role at school meetings, in the classroom. Students notice when I haven't been in the dining room, I'm expected to be a part of their life."

It is, in the final analysis, that involvement with the student that has drawn these headmasters from the College to the secondary schools. "The reason we decided to do this is that this is a very important period in the lives of young people," McNemar says. "They make a lot of decisions about their lives, and we realized that these schools contribute a great deal to their growth. We wanted to be a part of that."

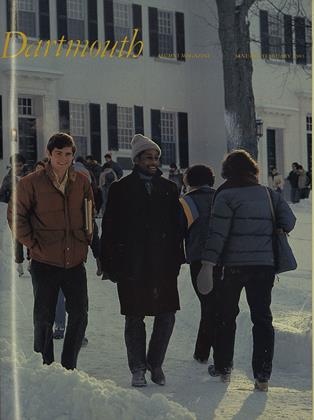

Britta and Donald McNemar at Phillips Academy, Andover

Charles Dey at Choate Rosemary Hall

Ralph Manuel at Culver Military Academy

David Shribman '76 is a reporter in the Washington bureau of The New York Times. He isa graduate of Swampscott (Mass.) HighSchool.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Report

January | February 1983 -

Feature

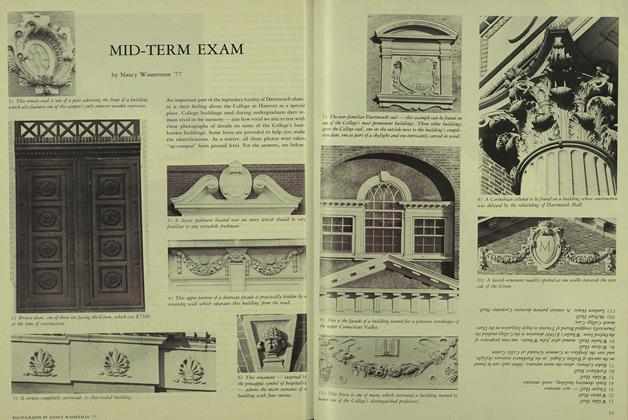

FeatureMID-TERM EXAM

January | February 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

January | February 1983 By Michael H. Carothers -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

January | February 1983 By Harry R. Zlokower -

Sports

SportsThe Ultimate Athlete

January | February 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

January | February 1983 By Francis R. Drury Jr.

David Shribman

Features

-

Feature

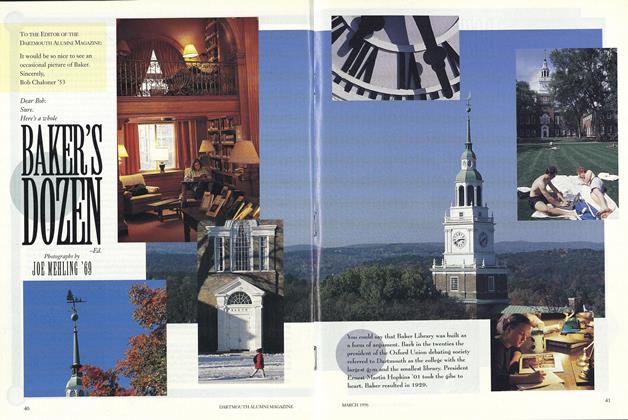

FeatureBAKER'S DOZEN

March 1996 -

Feature

FeatureMinimum Standards

APRIL • 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Feature

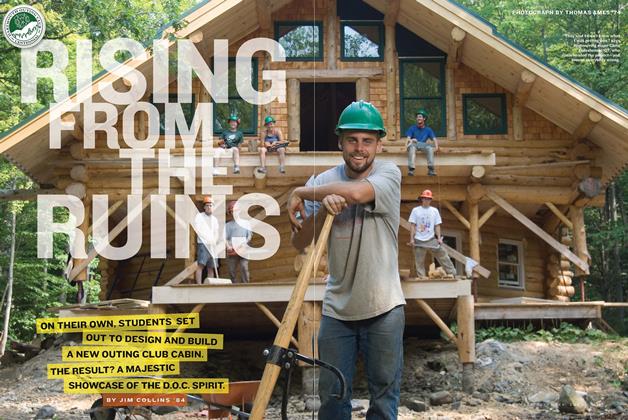

FeatureRising From the Ruins

Nov/Dec 2009 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureAt Dartmouth, the Intellectual Is on the Margin

MAY • 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Feature

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Feature

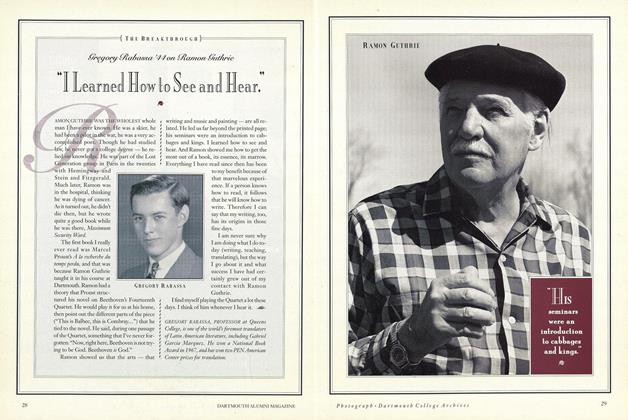

FeatureGregory Rabassa '44 on Ramon Guthrie

NOVEMBER 1991 By Ramon Guthrie