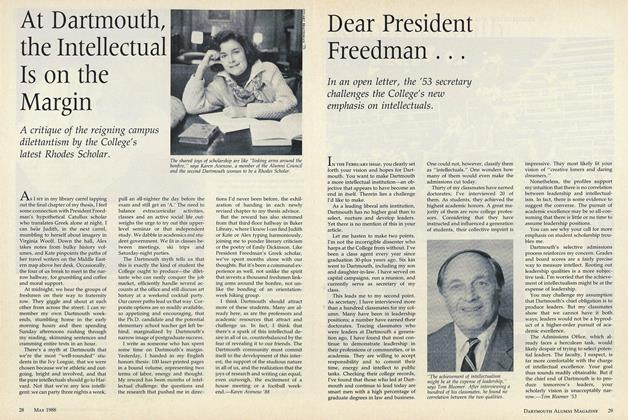

A critique of the reigning campus dilettantism by the College's latest Rhodes Scholar.

As I Sit in my library carrel tapping out the final chapter of my thesis, I feel some connection with President Freedman's hypothetical Catullus scholar who translates Greek alone at night. I can hear Judith, in the next carrel, mumbling to herself about imagery in Virginia Woolf. Down the hall, Alex takes notes from bulky history volumes, and Kate pinpoints the paths of her travel writers on the Middle Eastern map above her desk. Occasionally, the four of us break to meet in the narrow hallway, for grumbling and coffee and moral support.

At midnight, we hear the groups of freshmen on their way to fraternity row. They giggle and shout at each other from across the street. I can re- member my own Dartmouth week- ends, stumbling home in the early morning hours and then spending Sunday afternoons rushing through my reading, skimming sentences and cramming entire texts in an hour.

There's a myth at Dartmouth that we're the most "well-rounded" stu- dents in the Ivy League, that we were chosen because we're athletic and out- going, bright and involved, and that the pure intellectuals should go to Har- vard. Not that we're any less intelli- gent: we can party three nights a week, pull an all-nighter the day before the exam and still get an 'A.' The need to balance extracurricular activities, classes and an active social life out- weighs the urge to try out this upper- level seminar or that independent study. We dabble in academics and stu- dent government. We fit in classes be- tween meetings, ski trips and Saturday-night parties.

The Dartmouth myth tells us that this is exactly the kind of student the College ought to produce—the dilet- tante who can easily conquer the job market, efficiently handle several ac- counts at the office and still discuss art history at a weekend cocktail party. Our career paths lead us that way. Cor- porate options are so readily available, so appetizing and encouraging, that the Ph.D. candidate and the potential elementary school teacher get left be- hind, marginalized by Dartmouth's narrow image of postgraduate success.

I write as someone who has spent some time on Dartmouth's margin. Yesterday, I handed in my English honors thesis: 100 laser-printed pages in a bound volume, representing two terms of labor, energy and thought. My reward has been months of intel- lectual challenge: the questions and the research that pushed me in direc- tions I'd never been before, the exhil- aration of handing in each newly revised chapter to my thesis advisor.

But the reward has also stemmed from that third-floor hallway in Baker Library, where I know I can find Judith or Kate or Alex typing harmoniously, joining me to ponder literary criticism or the poetry of Emily Dickinson. Like President Freedman's Greek scholar, we've spent months alone with our thoughts. But it's been a communal ex- perience as well, not unlike the spirit that invests a thousand freshmen link- ing arms around the bonfire, not un- like the bonding of an orientation- week hiking group.

I think Dartmouth should attract more of these students. Many are al- ready here, as are the professors and academic resources that attract and challenge us. In fact, I think that there's a spark of this intellectual de- sire in all of us, counterbalanced by the fear of revealing it to our friends. The Dartmouth community must commit itself to the development of this inter- est, the support of the studious nature in all of us, and the realization that the joys of research and writing can equal, even outweigh, the excitement of a house meeting or a football week- end.-

The shared joys of scholarship are like "linking arms around thebonfire," says Karen Avenoso, a member of the Alumni Counciland the second Dartmouth woman to be a Rhodes Scholar.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

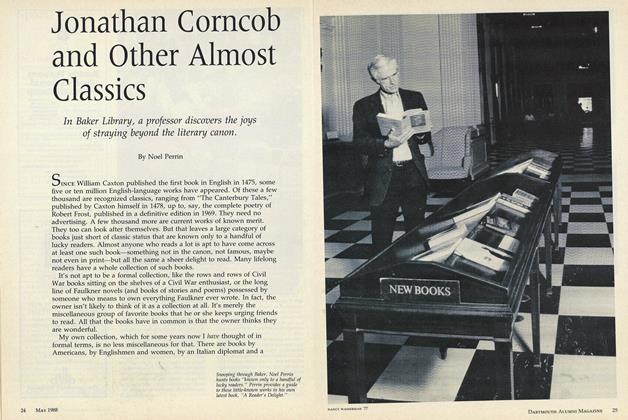

Cover StoryJonathan Corncob and Other Almost Classics

May 1988 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

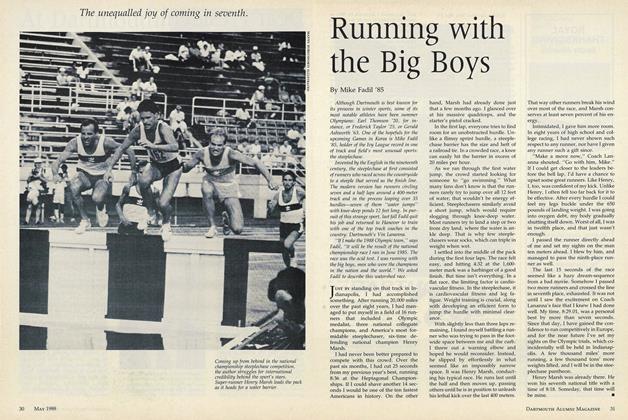

FeatureRunning with the Big Boys

May 1988 By Mike Fadil '85 -

Feature

FeatureDear President Freedman...

May 1988 By Tom Bloomer '53 -

Article

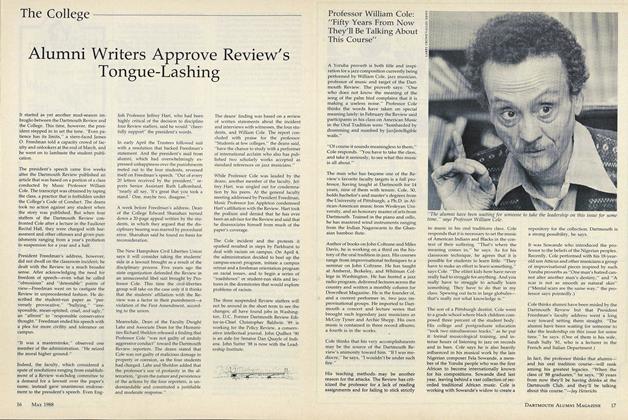

ArticleAlumni Writers Approve Review's Tongue-Lashing

May 1988 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorResponse: The Real Women's Issues

May 1988 By Mary G. Turco -

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

May 1988 By Jay Heinrichs

Karen Avenoso '88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Record-Breaking Reunion Week

JULY 1963 -

Feature

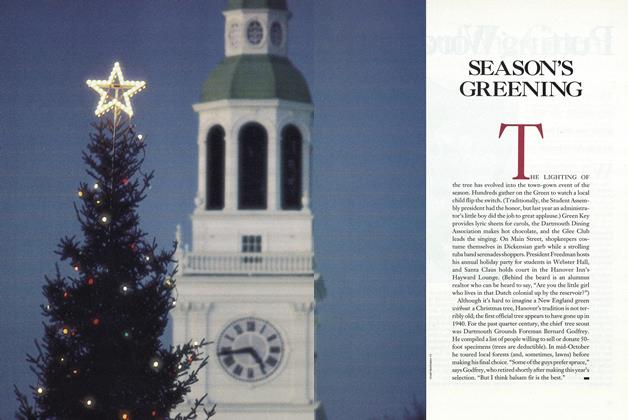

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Star from the East Named Dimitroff

MARCH 1995 By Bill Hartley '58 -

Feature

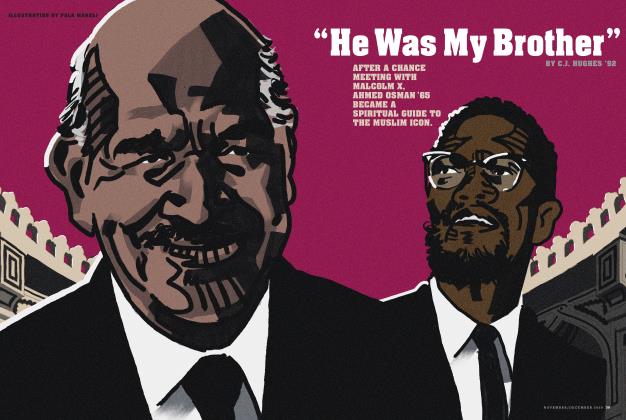

Feature“He Was My Brother”

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Cover Story

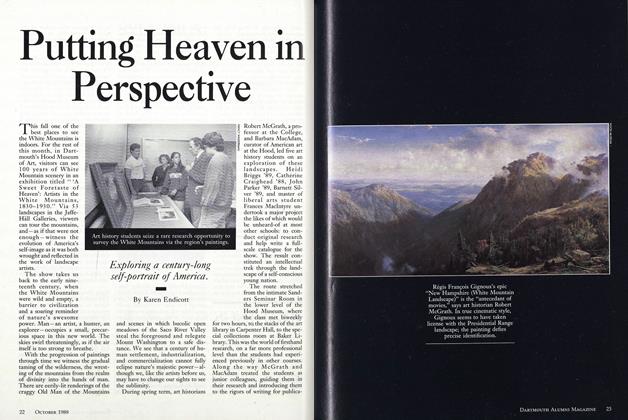

Cover StoryPutting Heaven in Perspective

OCTOBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureThirty Years After

June 1957 By RICHARD W. HUSBAND '26