The man who was the Magazine for four decades recalls the way it was

God delights in an odd number Numero Deus impure gaudet we are told by Virgil. And Shakespeare picks this up in The Merry Wives of Windsor when Falstaff remarks, "They say there is divinity in odd numbers."

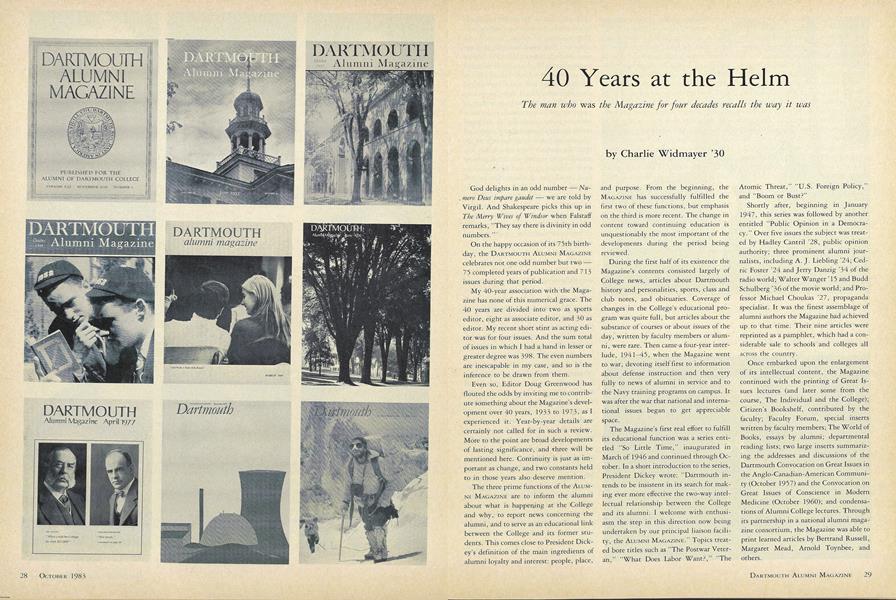

On the happy occasion of its 75 th birthday, the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE celebrates not one odd number but two 75 completed years of publication and 713 issues during that period.

My 40-year association with the Magazine has none of this numerical grace. The 40 years are divided into two as sports editor, eight as associate editor, and 30 as editor. My recent short stint as acting editor was for four issues. And the sum total of issues in which I had a hand in lesser or greater degree was 398. The even numbers are inescapable in my case, and so is the inference to be drawn from them.

Even so, Editor Doug Greenwood has flouted the odds by inviting me to contribute something about the Magazine's development over 40 years, 1933 to 1973, as I experienced it. Year-by-year details are certainly not called for in such a review. More to the point are broad developments of lasting significance, and three will be mentioned here. Continuity is just as important as change, and two constants held to in those years also deserve mention.

The three prime functions of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE are to inform the alumni about what is happening at the College and why, to report news concerning the alumni, and to serve as an educational link between the College and its former students. This comes close to President Dickey's definition of the main ingredients of alumni loyalty and interest: people, place, and purpose. From the beginning, the MAGAZINE has successfully fulfilled the first two of these functions, but emphasis on the third is more recent. The change in content toward continuing education is unquestionably the most important of the developments during the period being reviewed.

During the first half of its existence the Magazine's contents consisted largely of College news, articles about Dartmouth history and personalities, sports, class and club notes, and obituaries. Coverage of changes in the College's educational program was quite full, but articles about the substance of courses or about issues of the day, written by faculty members or alumni, were rare. Then came-a four-year interlude, 1941-45, when the Magazine went to war, devoting itself first to information about defense instruction and then very fully to news of alumni in service and to the Navy training programs on campus. It was after the war that national and international issues began to get appreciable space.

The Magazine's first real effort to fulfill its educational function was a series entitled "So Little Time," inaugurated in March of 1946 and continued through October. In a short introduction to the series, President Dickey wrote: "Dartmouth intends to be insistent in its search for making ever more effective the two-way intellectual relationship between the College and its alumni. I welcome with enthusiasm the step in this direction now being undertaken by our principal liaison facility, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE." Topics treated bore titles such as "The Postwar Veteran," "What Does . Labor Want?," "The Atomic Threat," "U.S. Foreign Policy, and "Boom or Bust?"

Shortly after, beginning in January 1947, this series was followed by another entitled "Public Opinion in a Democracy." Over five issues the subject was treated by Hadley Cantril '28, public opinion authority; three prominent alumni journalists, including A. J. Liebling '24; Cedric Foster '24 and Jerry Danzig '34 of the radio world; Walter Wanger '15 and Budd Schulberg '36 of the movie world; and Professor Michael Choukas '27, propaganda specialist. It was the finest assemblage of alumni authors the Magazine had achieved up to that time. Their nine articles were reprinted as a pamphlet, which had a considerable sale to schools and colleges all across the country.

Once embarked upon the enlargement of its intellectual content, the Magazine continued with the printing of Great Issues lectures (and later some from the course, The Individual and the College); Citizen's Bookshelf, contributed by the faculty; Faculty Forum, special inserts written by faculty members; The World of Books, essays by alumni; departmental reading lists; two large inserts summarizing the addresses and discussions of the Dartmouth Convocation on Great Issues in the Anglo-Canadian-American Community (October 1957) and the Convocation on Great Issues of Conscience in Modern Medicine (October I960); and condensations of Alumni College lectures. Through its partnership in a national alumni magazine consortium, the Magazine was able to print learned articles by Bertrand Russell, Margaret Mead, Arnold Toynbee, and others.

Inserts and special issues such as the two on Japan and engineering education might have sharpened reader awareness of the Magazine's intent to play a stronger educational role, but the best evidence was in the regular publication of separate articles

How Much Government?, The Economic Outlook, Automation, The Poet as Teacher, The Goals of a Business Society, Unrest in Latin America, National Security, The Common Market, War and History, A European Community, The Computer Revolution, Can Congress Survive?, The Movies as Art, Military Power: The Fading Persuader, World Understanding, Notes on the New Europe, The Philosophy of Culture, Federal Financing of Higher Education, The Classic Tradition of Judaism, The Hippie Ethic, Vietnam, The Dilemma of World Power, Man and His Environment, and Genetic Engineering. Many of these articles were written by Dartmouth faculty members, and an especially gratifying development was the growing number of articles contributed by alumni. If I could wish today's ALUMNI MAGAZINE one piece of good fortune, it would be a revival and increase of contents written for it by the Dartmouth faculty.

Another development with lasting effect was the gradual transformation of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE from a one-way to a two-way medium of communication between the College and the alumni. Articles by alumni, as mentioned, were one form of this, but the most striking evidence was the remarkable growth of the letters section. Letters to the editor were an insignificant part of the Magazine's contents for many years. Each issue had at most two or three letters of a mild nature and often no letters at all to print. It was not until 1934 that letters were moved from the tail end of the Magazine to the front. Alumni in those years apparently did not think of the Magazine as the place to make known their opinions about College events and policies. They were more inclined to write to the president. One would have expected a deluge of mail about the Orozco murals, which upset a great many alumni, but only six letters about them were printed over a period of four months. President Hopkins' mail basket, at the same time, was full.

Things began to change in February 1950 with a spirited response to Professor Bruce Knight's article, "Pseudo-Liberalism" (picked up by Reader's Digest), which attacked most so-called liberalism as nothing but socialism. Professor Herbert West's praise of Paul Blanshard's A?nericanFreedom and Catholic Power also propelled alumni to their typewriters, and the same was true of "Too Many Republicans" by Michael Cardozo '32, blaming the Selective Process for the overly conservative character of the Dartmouth alumni body. The letters section, now running to two or three pages rather than two or three lett ers, had become an estalished and widely read part of the Magazine, a trend which continues to this day.

Nothing in the '50s stirred up alumni letter-writers so much as architecture. Protests about the Choate Road dormitories were but a prelude to the outburst after the special issue of May 1957 devoted to plans for the Hopkins Center. Sixty letters in two issues led to the editor's declaring that nothing new was being said and the subject should be closed. This was the first of only two times when the volume of repetitive mail necessitated a deviation from the policy of printing all letters received (except those indulging in personal vituperation and those so factually off the mark that a revised letter was invited). The second occasion, setting the highwater mark in alumni mail, was the commencement valedictory of James Newton '68, printed in the July 1968 issue. In it he urged his classmates to refuse to serve in Vietnam if drafted. Letters from 90 alumni appeared in six issues, and seven pages of them in October 1968 required making a representative selection of full letters and excerpting the rest.

Since that time, alumni have unburdened themselves about the Wallace Affair, ROTC (the most persistent subject over the years and still with us), coeducation, the seizure of Parkhurst Hall, the Indian symbol, and the student strike of May 1970. Response to "think pieces" has been one of the most gratifying aspects of providing an open forum for alumni opinion, and alumni answering one another has been on the positive side. Certainly, by now, the letters section is established as a vital and valuable part of every issue of the Magazine. Two-way communication is a reality and is as untrammeled as it should be in a publication bearing Dartmouth's name. In going over back issues for this article, I was pleased to find something I wrote in 1948: "The College must never raise walls to freedom of inquiry, of thought, and of honestly expressed opinion." It bears repeating.

No account of the really big changes in the character and operations of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE could leave out the adoption, in the late '30s, of the class group subscription plan. The plan, in full force today, thanks to the unanimous support of the classes, is the bedrock of the Magazine's operating strength. It enables the Magazine to reach more than 90 percent of all alumni and, in combination with revenues from advertising, to maintain its financial independence.

Although the class of 1911 began its own group subscription in 1922, and 1910 and 1914 followed suit a few years later, the plan was not adopted widely until the fall of 1938. It had the backing of President Hopkins, the Dartmouth Alumni Council, and the Dartmouth Class Secretaries Association, and it was specifically brought into being by a special committee headed by Harold P. Hinman '10. Thirtynine classes joined the plan that first year; today, in an unbroken sequence, classes from 1908 to 1983 participate. In 1937 38, the last year before the group subscription plan was generally adopted, the Magazine with a circulation of 6,000 was reaching about half of the graduates of the College and only a little more than a third of all alumni. Today, its circulation of 41,000 includes 93 percent of all alumni and nearly 3,000 widows. It would be difficult to overstate the benefits the plan has brought to the MAGAZINE and ultimately to the College. If anyone is entitled to credit for the ongoing success of the plan, it is the class treasurer, who collects the annual dues that pay for each group subscription.

If the support of the class treasurers was one of the constants during the Magazine years under review, even more so was this true of the class secretaries, who provide the backbone of each issue by means of the class-notes section. At American Alumni Council conferences in years past there was rarely an editorial program that did not include some criticism of class notes as trivial and beneath the dignity of an institution of higher learning. The type of institution has some bearing, of course, but this view was: a perverse reading of the importance of alumni to American higher education. For a college such as Dartmouth, with its preeminent organization of classes and its unique sense of family, news of the men and women who attended the College and now represent it in the outside world is the most natural sort of contents for the Magazine to emphasize. In every one of our reader surveys, class notes were first by a wide margin. It is true that secretaries were periodically exhorted to stick to hard news and avoid the chit-chat, but if the College cares about its alumni as individuals, not in the mass, even chitchat has its virtues. In more recent years, the class newsletters have to some extent undercut the Magazine's reporting of alumni news, but an "official" cachet still is accorded the Magazine's class columns, and the news presented there can be read by the entire alumni body, not just by members of a single class. To anyone interested in human beings and their impressive and sometimes bizarre doings, the class-notes section makes good reading. There is always that special surge of interest when the reader spots, in bold type, the name of a Dartmouth friend.

One other constant in ALUMNI MAGAZINE history is the freedom with which the editor has been allowed to do his job. If I am convinced of anything, it is that this tradition is not in jeopardy, now or for the future. To one who knows the character and history of Dartmouth College, a contrary opinion is hard to understand. I prefer the phrase "editorial freedom" to "editorial independence." The Magazine has always been an integral part of the College's alumni program; it is not an island unto itself, although it has a clear responsibility to itself along with its higher responsibilities to the alumni and to the College. Without such self-interest, on which its integrity and credibility are based, it cannot do its job.

The point at which editorial freedom comes into fullest play is a nice question. It comes, I believe, in the implementation of the choices that have been made as to the contents of any given issue the writing, editing, and graphic presentation of them as the editor sees fit. While he does have the greatest, even the final, say in the determination of contents, the ideas, wisdom, and special knowledge of others are essential and of great value to him. An editor is importuned to print many things, and he must have his own selective process, but giving a sympathetic hearing to what is important to others does not compromise his freedom as editor.

The life of the College today is so much broader and more complex than it was in the years reviewed in this article that the editor's task is correspondingly more demanding. Fortunately, he has the freedom, like editors before him, to take new initiatives and to shape the Magazine to the needs of the time as he sees them. This is what gives us the soundest confidence in the Magazine as it marks its 75 th birthday and moves ahead to the next big milestone, its 100 th.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

October 1983 By Horace Porter -

Feature

FeatureArtists in Residence

October 1983 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Feature

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

October 1983 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureMeet Ted Leland

October 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureThe Widmayer Touch

October 1983 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureLessons from the Past

October 1983 By Allen A. Ryan '66

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBE Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

MARCH 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

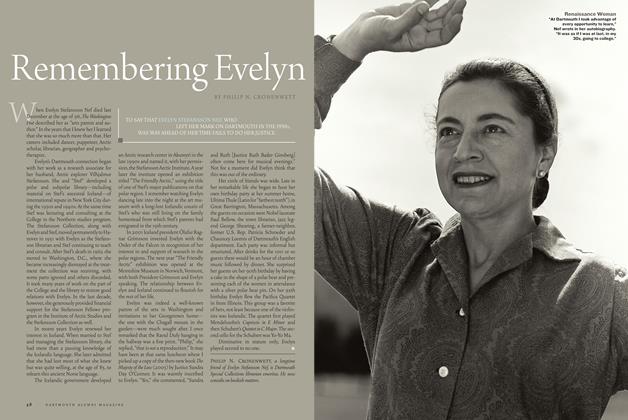

FeatureRemembering Evelyn

Mar/Apr 2010 By PHILIP N. CRONENWETT -

Feature

FeatureThe Dinan Decade

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn the Ranks of the Learned

MARCH 1995 By Tamar Schreibman '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO RESTORE THE ENVIRONMENT

Sept/Oct 2001 By THEODOR "DR. SEUSS" GEISEL '25