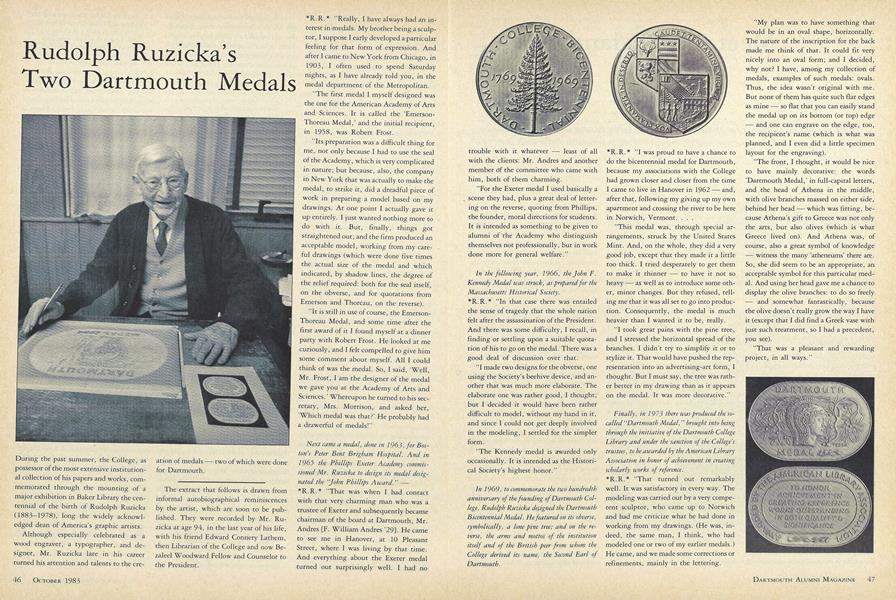

During the past summer, the College, as possessor of the most extensive institutional collection of his papers and works, commemorated through the mounting of a major exhibition in Baker Library the centennial of the birth of Rudolph Ruzicka (1883-1978), long the widely acknowledged dean of America's graphic artists.

Although especially celebrated as a wood engraver, a typographer, and designer, Mr. Ruzicka late in his career turned his attention and talents to the creation of medals two of which were done for Dartmouth.

The extract that follows is drawn from informal autobiographical reminiscences by the artist, which are soon to be published. They were recorded by Mr. Ruzicka at age 94, in the last year of his life, with his friend Edward Connery Lathem, then Librarian of the College and now Bezaleel Woodward Fellow and Counselor to the President.

*R.R.* "Really, I have always had an interest in medals. My brother being a sculptor, I suppose I early developed a particular feeling for that form of expression. And after I came to New York from Chicago, in 1903, I often used to spend Saturday nights, as I have already told you, in the medal department of the Metropolitan.

"The first .medal I myself designed was the one for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. It is called the 'EmersonThoreau Medal,' and the initial recipient, in 1958, was Robert Frost.

"Its preparation was a difficult thing for me, not only because I had to use the seal of the Academy, which is very complicated in nature; but because, also, the company in New York that was actually to make the medal, to strike it, did a dreadful piece of work in preparing a model based on my drawings. At one point I actually gave it up entirely. I just wanted nothing more to do with it. But, finally, things got straightened out; and the firm produced an acceptable model, working from my careful drawings (which were done five times the actual size of the medal and which indicated, by shadow lines, the degree of the relief required: both for the seal itself, on the obverse, and for quotations from Emerson and Thoreau, on the reverse).

It is still in use of course, the EmersonThoreau Medal, and some time after the first award of it I found myself at a dinner party with Robert Frost. He looked at me curiously, and I felt compelled to give him some comment about myself. All I could think of was the medal. So, I said, 'Well, Mr. Frost, I am the designer of the medal we gave you at the Academy of Arts and Sciences.' Whereupon he turned to his secretary, Mrs. Morrison, and asked her, Which medal was that?' He probably had a drawerful of medals!"

Next came a medal, done in 1963, for Boston's Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. And in1965 the Phillips Exeter Academy commissioned Mr. Ruzicka to design its medal designated the "John Phillips Award." *R.R.* "That was when I had contact with that very charming man who was a trustee of Exeter and subsequently became chairman of the board at Dartmouth, Mr. Andres {F. William Andres '29}, He came to see me in Hanover, at 10 Pleasant Street, where I was living by that time. And everything about the Exeter medal turned out surprisingly well. I had no trouble with it whatever least of all with the clients: Mr. Andres and another member of the committee who came with him, both of them charming.

"For the Exeter medal I used basically a scene they had, plus a great deal of lettering on the reverse, quoting from Phillips, the founder, moral directions for students. It is intended as something to be given to alumni of the Academy who distinguish themselves not professionally, but in work done more for general welfare."

In the following year, 1966, the John F.Kennedy Medal was struck, as prepared for theMassachusetts Historical Society.

*R.R.* "In that case there was entailed the sense of tragedy that the whole nation felt after the assassination of the President. And there was some difficulty, I recall, in finding or settling upon a suitable quotation of his to go on the medal. There was a good deal of discussion over that.

"I made two designs for the obverse, one using the Society's beehive device, and another that was much more elaborate. The elaborate one was rather good, I thought; but I decided it would have been rather difficult to model, without my hand in it, and since I could not get deeply involved in the modeling, I settled for the simpler form.

"The Kennedy medal is awarded only occasionally. It is intended as the Historical Society's highest honor."

In 1969, to commemorate the two hundredthanniversary of the founding of Dartmouth College, Rudolph Ruzicka designed the DartmouthBicentennial Medal. He featured on its obverse,symbolically, a lone pine tree; and on the reverse, the arms and mottos of the institutionitself and of the British peer from whom theCollege derived its name, the Second Earl ofDartmouth.

*R.R.* "I was proud to have a chance to do the bicentennial medal for Dartmouth, because my associations with the College had grown closer and closer from the time I came to live in Hanover in 1962 and, after that, following my giving up my own apartment and crossing the river to be here in Norwich, Vermont. . . .

"This medal was, through special arrangements, struck by the United States Mint. And, on the whole, they did a very good job, except that they made it a little too thick. I tried desperately to get them to make it thinner to have it not so heavy as well as to introduce some other, minor changes. But they refused, telling me that it was all set to go into production. Consequently, the medal is much heavier than I wanted it to be, really.

"I took great pains with the pine tree, and I stressed the horizontal spread of the branches. I didn't try to simplify it or to stylize it. That would have pushed the representation into an advertising-art form, I thought. But I must say, the tree was rather better in my drawing than as it appears on the medal. It was more decorative."

Finally, in 1973 there was produced the socalled "Dartmouth Medal," brought into beingthrough the initiative of the Dartmouth CollegeLibrary and under the sanction of the College'strustees, to be awarded by the American LibraryAssociation in honor of achievement in creatingscholarly works of reference.

*R.R.* "That turned out remarkably well. It was satisfactory in every way. The modeling was carried out by a very competent sculptor, who came up to Norwich and had me criticize what he had done in working from my drawings. (He was, indeed, the same man, I think, who had modeled one or two of my earlier medals.) He came, and we made some corrections or refinements, mainly in the lettering.

"My plan was to have something that would be in an oval shape, horizontally. The nature of the inscription for the back made me think of that. It could fit very nicely into an oval form; and I decided, why not? I have, among my collection of medals, examples of such medals: ovals. Thus, the idea wasn't original with me. But none of them has quite such flat edges as mine so flat that you can easily stand the medal up on its bottom (or top) edge and one can engrave on the edge, too, the recipient's name (which is what was planned, and I even did a little specimen layout for the engraving).

"The front, I thought, it would be nice to have mainly decorative: the words 'Dartmouth Medal,' in full-capital letters, and the head of Athena in the middle, with olive branches massed on either side, behind her head which was fitting, because Athena's gift to Greece was not only the arts, but also olives (which is what Greece lived on). And Athena was, of course, also a great symbol of knowledge witness the many 'atheneums' there are. So, she did seem to be an appropriate, an acceptable symbol for this particular medal. And using her head gave me a chance to display the olive branches: to do so freely and somewhat fantastically, because the olive doesn't really grow the way I have it (except that I did find a Greek vase with just such treatment, so I had a precedent, you see).

"That was a pleasant and rewarding project, in all ways."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

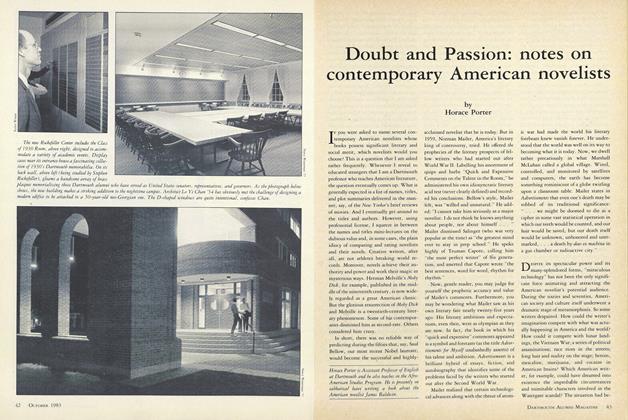

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

October 1983 By Horace Porter -

Feature

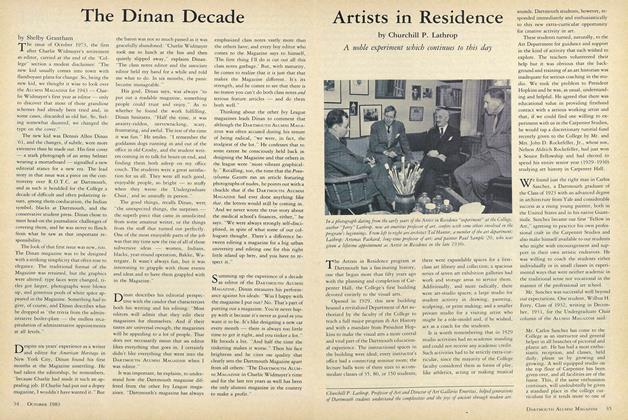

FeatureArtists in Residence

October 1983 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Feature

Feature40 Years at the Helm

October 1983 By Charlie Widmayer '30 -

Feature

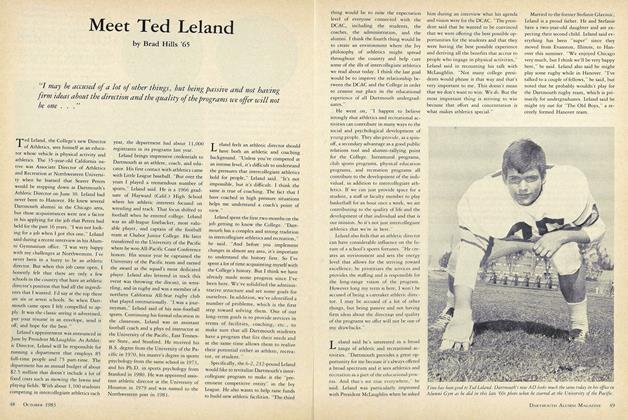

FeatureMeet Ted Leland

October 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

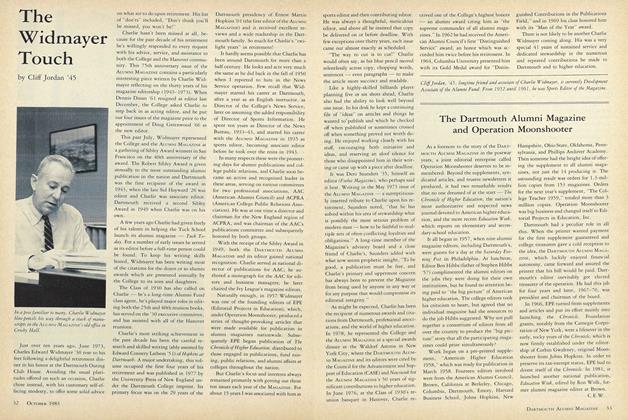

FeatureThe Widmayer Touch

October 1983 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureLessons from the Past

October 1983 By Allen A. Ryan '66