A DOCTOR'S GUIDE TO FEEDING YOUR CHILD by Stephen J. Atwood '68, M.D. Mdcmillan, 1982. 248 pp. $12.95

If your kids are anything like mine, you've occasionally wondered whether they ever ate enough to keep the proverbial bird alive. For years we considered our daughter an air fern, as she seemed to be able to grow and develop fine without any discernible caloric intake. A friend of mine (a pediatrician, as a matter of fact) was convinced that about 75% of her two-year- old son's muscle was composed of the graham crackers he subsisted on.

My kids have an uncanny knack of being able to make unbelievable assessments of food visually. In one glance they can 1) assess the protein content (if it's greater than 10%, it's rejected); 2) assay for "empty calories" (any item that's acceptable is about 40% sucrose and is devoid of vitamins); 3) detect whether there's a trace of whole wheat flour on the one hand, or a shred of green vegetable on the other (the discovery of either constitutes an automatic rejection); and 4) pronounce with deadly finality, "That's yucky!" and that's the end of that.

Back when I was in medical school (sometime between the pre-Cambrian and the med-macrobiotic; eras), we weren't taught a whole lot about nutrition for healthy kids. Oh, we learned that diabetics ought not to eat much sugar, and that heart patients needed to watch their salt. But it was pretty much taken for granted that a pregnant woman shouldn't gain more than 20 pounds total, and just about everything we needed to know about infant nutrition was printed on the side of a can of formula. But then came Vietnam, and the Greening of America, and the Sexual Revolution, and a return to Nature.

Don't get me wrong: the movement for natural childbirth and natural feeding (breast) and an interest in good health through nutrition are all marvelous evolutions chat I welcome and applaud. But it's taken medical science as it's taught in the medical schools a long time to catch up. I learned almost everything I know about infant and childhood nutrition after I became a medical school faculty member and a board-certified pediatrician. And after I became a certified mother. And I've made it a point to see that the medical students I teach know at least as much about child nutrition as the mothers of their patients do.

Along comes a book written by a gentle and sensible pediatrician. Dr. Stephen Atwood, Director of Education and Asso- ciate Professor of Clinical Pediatrics at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center. The book is a very up-to-date and accurate discussion of pediatrics' current concept of nutrition for children, with emphasis on the benefits of excellent nutrition in pregnancy and the biologic advantages of breastfeeding. But it's all done in a casually scientific way that does not insult the reader's intelligence and might enchant even a father to read on. Dr. Atwood debunks (correctly) the myths about hyperactivity and learning disabilities being related to "food additives" and "sugar." There is also a timely discussion of the perils of teenage anorexia and bulimia, as well as fad diets and vegetarianism. But it's all low-key you don't get the feeling that this is a book for nutrition freaks. As a distillation of the current state-of-the-art, it ought to be required reading for thirdyear medical students and pediatric interns. We pediatricians all ought to be so sensible and knowledgeable in the nutritional advice we foist on our patients and families. And it sure would have been a great book for me to have had around the house when my toddler decided she could easily live on grapes and vanilla yogurt forever.

Dr. Stashivick, has been an assistant professor ofclinical maternal and child health at the Dart-mouth Medical School since 1981, and themother of two children for a bit longer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

October 1983 By Horace Porter -

Feature

FeatureArtists in Residence

October 1983 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Feature

Feature40 Years at the Helm

October 1983 By Charlie Widmayer '30 -

Feature

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

October 1983 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

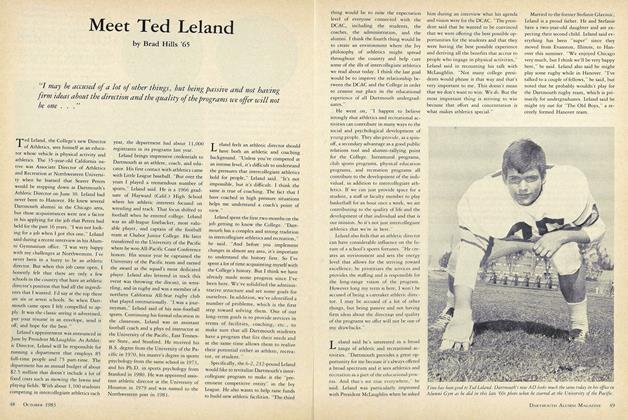

FeatureMeet Ted Leland

October 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureThe Widmayer Touch

October 1983 By Cliff Jordan '45

Books

-

Books

BooksA GENERATION OF ILLUSTRATORS AND ETCHERS.

January 1961 By ELLEN MARY JONES -

Books

BooksV AS IN VICTIM

December 1945 By H. M. Dargan. -

Books

BooksShelf Life

Mar/Apr 2004 By Matthew Feinstein '04 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN LABOR UNIONS; ORGANIZATION, AIMS, AND POWER.

July 1950 By Robert Swanton -

Books

BooksAMATEUR SUGAR MAKER.

APRIL 1972 By RUTH J. WELLINGTON -

Books

BooksYOU COME TOO: FAVORITE POEMS FOR YOUNG READERS.

December 1959 By STEARNS MORSE