Drawings at Dartmouth give "a fresh look"

At the time of his unexpected death of a heart attack at the age of 69 on April 15, 1925, in his adopted city of London, John Singer Sargent was probably the best known American artist of the day. His fame had been rivalled only by a handful of contemporary painters: Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), the Philadelphia portraitist; Winslow Homer (1836-1910), who specialized in landscape and marine subjects; and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834—1903), who abandoned his native Lowell, Massachusetts, for success in London and Paris. Only Cassatt, living in Paris, survived Sargent, and deteriorating eyesight kept her from painting for the last decade of her life.

Born in Florence, Italy, January 10, 1856, John Singer Sargent led an extraordinary childhood. The Sargent family was engaged in a near-constant state of travel, "a never-ending Grand Tour," as the critic Donelson Hoopes noted. Sargent's mother, Mary Newbold Singer, the daughter of a wealthy Philadelphia fur merchant, had married Dr. FitzWilliam Sargent, a distinguished Philadelphia surgeon and amateur carver in wood, in 1850. In 1854, she persuaded him to retire from his practice and permanently live in Europe.

The Sargents moved with their three surviving children (two died in infancy), John and his sisters, between the fashionable spots of Europe: Florence, Rome, San Remo, Nice, the Alps, Spain, London. Although affluent, their circumstances were not so grand as to allow total independence, and frequently they economized by traveling out of season.' The children's education was not formal and tended to focus on Mary Sargent's interests in art, music, and literature. Sargent inherited from his mother her almost pathological desire to travel, to be a nomad. For the last 40 years of Sargent's life, London was his home, but he was away at least as often as he resided there.

His first training in art came at the age of 12 when his parents arranged for him to be instructed by a minor German-American painter in Rome, Carl Welsch. He undertook formal studies in 1870 when he enrolled at the Accademia della Bella Arte in Florence. While his mother had encouraged his early ability to draw, Sargent took to painting with enthusiasm. For him, there was no doubt about his future career; he would be an artist, a painter in spite of his father's urgings that he become a naval officer.

In Paris in 1874, the 18 year old Sargent became a pupil of Charles August Emile Duran, who styled himself "Carolus-Duran." Carolus-Duran was the most popular portraitist in Paris, and a successful pprenticeship would virtually guarantee the young Americanborn painter a lucrative practice in France. Sargent remained with Carolus-Duran until 1879, and then opened his own studio in Paris. In 1884 he left for London, his "home" for the next 40 years.

Sargent was an American by birth and by his own strong emotional attachment to the,.U.S. Born abroad of American parents, he was 20 years old when he made his first visit to his parents' home country. Handsome, a talented musician, multilingual, and an ground, Sargent made a favorable impression on his new American acquaintances. During the next 50 years, he was to make many return visits, particularly from 1890 on. In fact, at the time of his death, he was preparing for his departure to Boston two days later.

Following his untimely death, Sargent was the subject of two memorial exhibitions, one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the other at the Royal Academy (to which he had been elected in 1897) in London. As Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer, writing in the introduction to the catalogue accompanying the exhibition at the Metropolitan, noted, "Everywhere he had won the admiration of the competent in matters of arts, and in England and America, a popular fame unequalled in our time."

THE recent exhibition of drawings in the galleries of the Hopkins Center at Dartmouth College (September 10 November 27, 1983) enabled visitors to see John Singer Sargent as far more than "the last of the great portrait painters working in the grand manner" (Hoopes, The Private World of JohnSinger Sargent, 1964). Rather, one saw him as a superb draughtsman, a brilliant watercolorist, and the major muralist of his day. Still unexplored are his late effors as a sculptor in bronze and as a lithographic printmaker.

Indisputably, Sargent is remembered first for his portraits of figures of the nobility such as Lady Warwick and the Dutchess of Portland, of literary luminaries such as Henry James and Robert Louis Stevenson, and of fellow artists such as William Merritt Chase. He was the master of fashionable portraiture, earning enormous fees for recording the elegance and would-be elegance of distinguished Edwardians and well to do Americans. His technical virtuosity and audacious handling of both paint and his subjects won him a ready following. As one recent critic, Warren Adelson, noted, "During the nineties, it had ceased to be a question of who could be painted by Sargent; the question was, whom would he find time to paint."

The Dartmouth exhibition presented 65 drawings by Sargent given by his sisters, Violet and Emily, to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., augmented by ten others which the same donors presented to Dartmouth in 1929. The majority of these drawings deal with the three mural projects which dominated Sargent's work for the last 35 years of his life.

In 1890 while visiting Boston to solicit portrait commissions, the 34 year old artist was asked by the recentlyopened Boston Public Library to execute a mural project. Choosing as his subject the history of religion, he continued to labor on the mural until its completion in 1916. However, Sargent could not abandon the requests for portraits that in effect provided the opulent income to allow him the luxury of working on the mural projects and of traveling to the fashionable spas of Europe and his beloved retreats on Corfu, Majorca, Capri, and Venice. His second visit to America in 1890, for example, produced no fewer than 40 portrait commissions.

Sargent's growing frustration as high society portraitist frequently manifested itself. Writing to a relative in 1907, he quipped, "A portrait is a painting with a little something wrong about the mouth." By 1909, the artist had all but given up portraiture in oil, except for members of his family and the likenesses of John D. Rockefeller and President Woodrow Wilson that he undertook after World War I for the benefit of the Red Cross.

His second mural project was the decoration of the rotunda in the Museum of Fine Arts at Boston for which he signed a contract in 1916; appropriately, the subject was "Classical and Romantic Art." In 1922 he accepted a ommission to decorate the main staircase of Widener Library at Harvard University as a memorial for the school's graduates who had died in the war. Some five years earlier, Sargent had traveled to the front in France to prepare sketches for a monumental oil painting entitled "Gassed," in the Imperial War Museum in London.

AT his death, Sargent was, as noted earlier, the best known artist of his generation. He had won numerous prizes, from the first honorable mention at the Salon of the Academy in Paris in 1878 for "The Oyster Gatherers of Cancale" to honorary degrees from the University of Pennsylvania, Oxford, Cambridge, Yale, and Harvard, the last two in the same year, 1916. His large portraits, generally about seven feet high, brought him fees in excess of $5,000 and he regularly executed, without assistance, ten to twelve each year, sometimes as many as 25. Lionized like his historic antecedents Velazquez, Hals, Van Dyck, Reynolds, and Ingres, Sargent was subject to the charge of superficiality, and after his death many critics saw only flashiness in his technical virtuosity. His reputation went into a sharp decline.

The last two decades have seen a careful, balanced reassessment of his achievements, and an understanding of his role as practitioner, rather than theorist. As Mrs. Van Rensselaer wrote the year after his death, "Heredity favored him; environment and circumstance stimulated and encouraged him." By presenting the exhibition John Singer Sargent Drawings, Dartmouth, too, takes a fresh look at one of America's great artists. From his early academic landscapes, to his contact with Impressionism in the late 1880s, and his broad, bold style of the 1890s, one sees the growth which culminates in his late realist mural projects. Yet to see Sargent only as an extraordinary portraitist the man his contemporary, \Auguste Rodin, referred to as "the Van Dyck of our times" is to view an artist of rare ability in too narrow a vein. The Dartmouth presentation of his landscapes and his mural designs reveals the astonishing range which justifies the positive reappraisal of his role by the current generation of art historians and critics.

Olimpio Fusco.This forceful study was probably donearound 1900. The date is suggested by the type of paperused. Fusco was a model used by Sargent in London; hisname and address appear in the artist's handwriting at thelower right. Charcoal on beige paper, 24 1/2 x 18⅝ inches.Corcoran Gallery of Art.

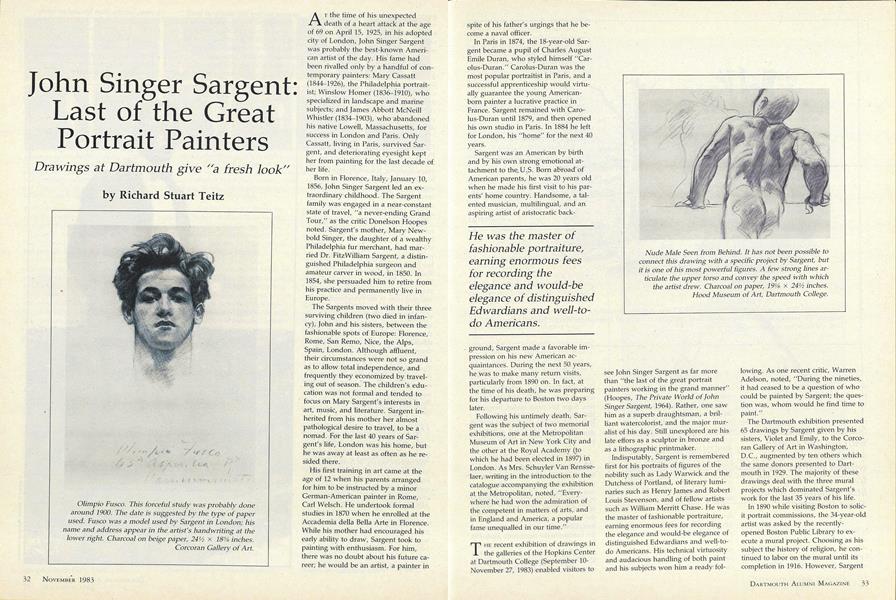

Nude Male Seen from Behind. It has not been possible toconnect this drawing with a specific project by Sargent, butit is one of his most powerful figures. A few strong lines articulate the upper torso and convey the speed with which the artist drew. Charcoal on paper, 19 1/8 x 24 1/2 inches.Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College.

Forest Scene. This drawing of trees was done in 1871 near Ramsau, in southern Germany by the 15-year-old Sargent. The young artist uses contracts of darks and lights to create an atmospheric effect. Charcoal on paper, 11⅜ X 15⅜ inches. Corcoran Callery of Art.

Falling Nude Male. This enigmatic figure may well have been intended as a study for one of the falling men in a mural composition in theBoston Public Library. If so, it probably is datable around 1918. Charcoalon paper, 24 1/2 x 18 3/4 inches. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth

Somewhat frustratedwith his role as highsociety portraitist, hewrote a relative, "A portrait is a painting with alittle something wrongabout the mouth."

He was the master offashionable portraiture,earning enormous feesfor recording theelegance and would beelegance of distinguishedEdwardians and well to do Americans.

To his contemporaryAuguste Rodin he was"the Van Dyck of ourtimes."

Richard Stuart Teitz, Professor of Art atDartmouth, is also Director of theHood Museum of Art.Suggestions for Further Reading McKibbin, David. Sargent's Boston. Catalogue of an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1956. Mount, Charles Merrill. John SingerSargent: A Biography. New York: Norton, 1955. Ormond, Richard. John Singer Sargent:Paintings, Drawings, Water colors. New York: Harper & Row, 1970. Ratcliff, Carter. John Singer Sargent. New York: Abbeville Press, 1982.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

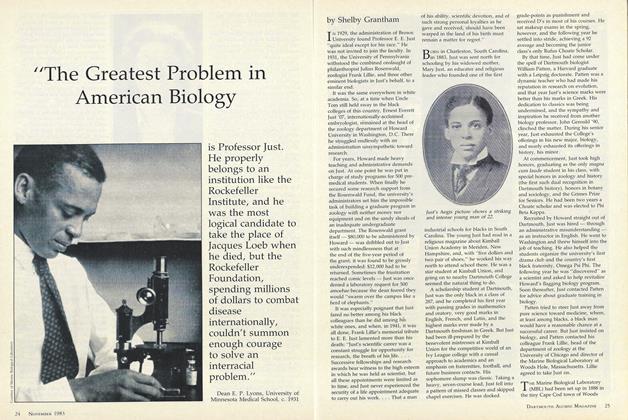

Feature"The Greatest Problem in American Biology

November 1983 -

Feature

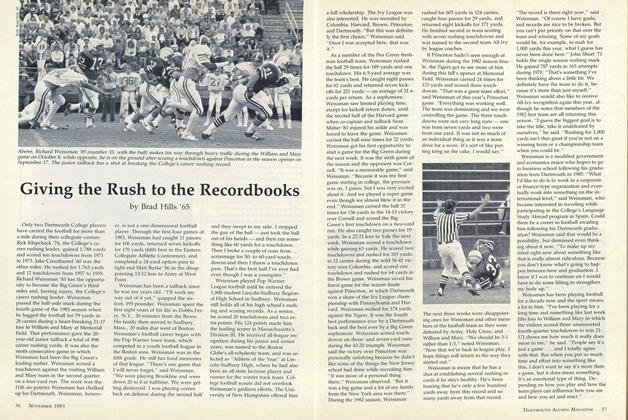

FeatureGiving the Rush to the Record books

November 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Sports

SportsSports

November 1983 By Kathy Slattery -

Books

BooksAll Biology Is Indebted . . .

November 1983 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

November 1983 By Burr Gray -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

November 1983 By Anne Barschall

Richard Stuart Teitz

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMcCulloch Heads Council

JULY 1971 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Rassias

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

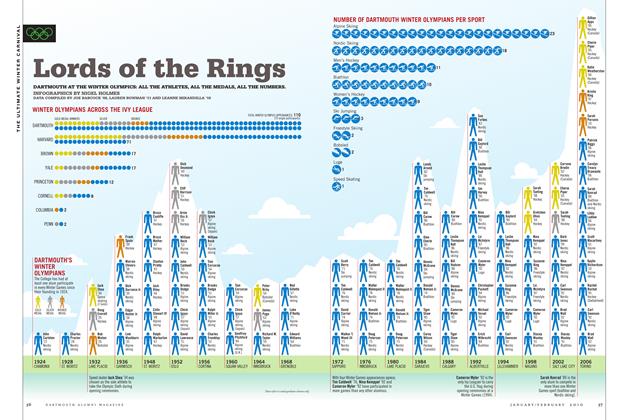

FeatureLords of the Rings

Jan/Feb 2010 -

Feature

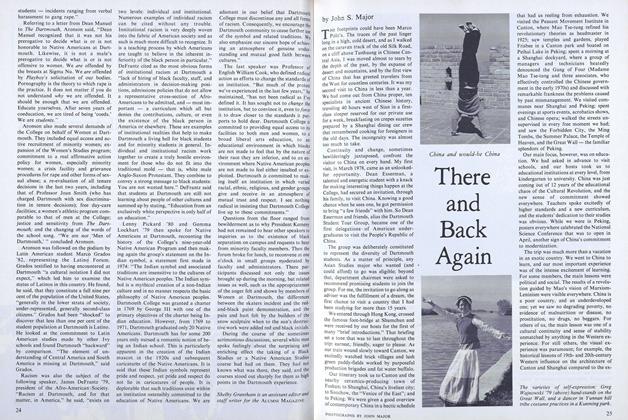

FeatureThere and Back Again

April 1979 By John S. Major -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Cover Story

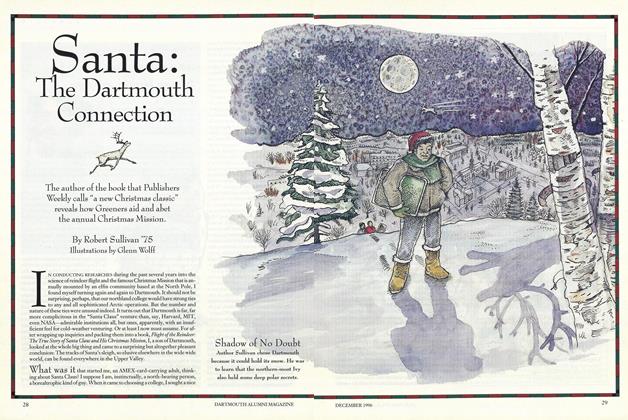

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

DECEMBER 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75