By Alexander Laing'25. New York: American Heritage Press,1971. 536 pp. Profusely illustrated. $17.50.

When Americans tend to think at all about their maritime heritage, they generally dwell upon the achievements which American technology has bestowed upon the world. Seen from this perspective, American maritime history begins with the Mayflower and ends with nuclear submarines capable of girdling the world without surfacing.

American Ships undertakes to do more than rectify these and other misconceptions about American maritime history—no mean feat in itself. Unobtrusively, yet forcefully, it sets out to revise our whole image of ourselves and our relationship to the world at large and our environment in particular. It begins by describing the grace and technological sophistication of such indigenous craft as the Peruvian balsa raft with its system of guara boards (centerboards), the Eskimo kayak and umiak, and the Indian birchbark canoe. In the best sense, these were products of a close interrelationship between man and his environment. They illustrate perfectly Laing's contention that there is no "ultimate" design, but only the right design for the right task and local conditions. The bark canoe and the Eskimo kayak, particularly the latter, represented "a Tightness that blended continually into the lives of its developers... as pure and uncluttered in conceptual form as a primary formula in scientific research."

Sadly, Europeans could not appreciate watercraft as a blending of man and his environment when they came to the New World. The native craft seemed strangely unsophisticated. Rather than using technology in conjunction with the environment to foster a mutually beneficial relationship, Europeans sought to use technology to dominate and exploit resources that had previously served principally for survival. Ships played a significant role in this activity which has led, today, to the belated awareness that the environment is not infinitely exploitable.

It is Mr. Laing's contention that marine design and technology—as with so many other aspects of European culture—may be primarily ascribed to economic or military needs. The bulk of the book demonstrates how these two motivating forces shaped the evolution of shipbuilding in North America. The history of American whaling provides the principal theme of the work, since it constitutes the most striking example of conflict between indigenous and European approaches to the resources of the New World.

Watercraft designed for the express purposes of sealing and whaling are among the oldest known boats in America. European settlers turned to native designs because they were quieter and more agile—the chief qualities required of pursuing craft—than the heavier European boats. The Yankee cedar whaleboat, an adaptation of the birchbark canoe, proved the most efficacious instrument for hunting whales in the world and enabled New Englanders to rival and then surpass European fisheries in the venture of reducing huge submersible mammals to barrels of oil and bundles of bone.

Whaling was not the only preoccupation of the colonists, however, and Laing gives ample treatment to American commercial ships—-sail and steam—and naval vessels. Traditionalists accustomed to viewing packets and clipper ships as the ultimate expression of beauty and technology in marine design may be disconcerted by the tenor of the coverage Laing gives these vessels. For him, ships do not exist in isolation, as objects to be admired nostalgically. He talks as much, or more, about men—designers, captains, deckhands—as he does about the ships themselves.

With a novelist's flair for narrative, and a poet's sense of irony (he is both poet and novelist), Laing turns what might be a relatively dry recital of names, facts and dates into a fascinating story in which individual visionaries set aside tradition to experiment with untried concepts in the quest for ever faster means of moving ships through the water or, in the case of naval design, of removing them violently from their element. Above all, he examines the motivations that, in the case of merchant vessels, begat the race for speed at all costsand, in the case of whaling, led to the remorseless hunting of leviathan, now all but extinct thanks to the horror of modern factory ships.

The illustrations in American Ships are fascinating in their own right, and they also remind us that the author has not produced a "coffee-table" book, the perfect gift for that sailing friend. It is a thoughtful, often philosophical, work of serious history, and like all .rood historical works its lesson is beamed directly at the present: "If we are luck, man's greatest achievement of the lucky, few years may be his realization at last next everything he makes and uses—not forgetting his ships—should be designed to work no injury upon the natural world, within which his own survival is linked more than symbolically to the long survival of leviathan."

Mr. Nichols, Dartmouth Professor of RomanceLanguages and Literatures, andChairman of the Freshman Tutorial Program,teaches The Nature and Criticism ofliterature.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

February 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

February 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSymphony Conductor

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureExecutive Exporter

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSnow Engineer

February 1972

STEPHEN G. NICHOLS JR. '58

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Books

BooksDistant Drum

December 1980 By Everett Wood '38 -

Books

BooksOuting Club Publishes A New Trail Guide

OCTOBER 1968 By JOHN R. PERSON '69 -

Books

BooksDANIEL WEBSTER

January, 1931 By Leon B. Richardson -

Books

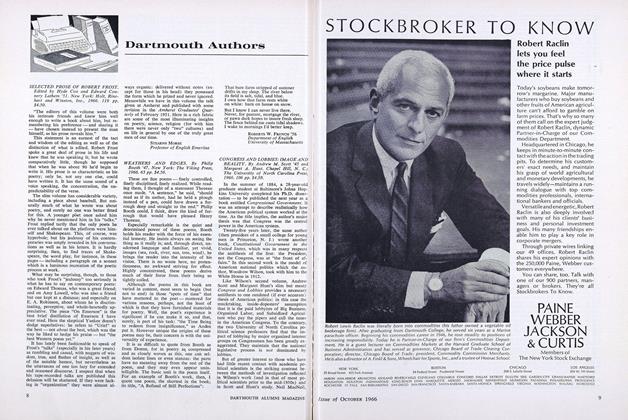

BooksSELECTED PROSE OF ROBERT FROST.

OCTOBER 1966 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksLines for a Tomb-Stone

MAY 1932 By William Kimball flaccus