ARABS IN THE JEWISH STATE by Professor Ian S. Lustick University of Texas, 1980 385 pp. $19.95; $10.95, paper

Since the establishment of the state of Israel 33 years ago, Israel's Arab minority has been without a political party of its own. Nor have any Arab economic, social, cultural, or professional organizations of major importance come into being. In all of Israel there are no Arab-owned banks, no independent Arab newspapers or mass-based civil rights organizations, no Arab-controlled businesses or farms of appreciable size or significance.

In Arabs in the Jewish State, a detailed study developed out of hundreds of interviews with Israeli Arabs and Jewish policymakers, lan Lustick, an assistant professor of government at Dartmouth, argues cogently that this situation is being perpetuated by an interrelated system of controls exercised by Israeli authorities over every major aspect of Arab life in Israel.

Going back to the days of the Basel Congresses and the Balfour Declaration, Lustick points to a marked failure on the part of early Zionist theoreticians to define the role and status of an Arab population in a Jewish state. This, Lustick maintains, contributed to creating an atmosphere in which the ideal of strict equality of all citizens in a Jewish state was frequently undermined by the exigencies of the moment, particularly in the first years of statehood when civilian officials as well as the military administration looked upon the vast majority of Israel's native Arab population as a potential threat to Israel's welfare.

i Significant economic and educational ine- qualities between Israeli Arabs and Jews have contributed to creating a system of internal colonialism with the overriding objective of the stronger group controlling the weaker minority, according to Lustick, who defines this system in terms of three components of control ― segmentation, dependence, cooptation ― each of which he then relates to historical and cultural circumstances, Jewish institutional factors, and Israeli government policies.

In contradiction to Israel's stated policy of achieving complete integration of its minorities into all spheres of life, Lustick identifies a number of official and quasi-official organizations whose policies unquestionably reinforce the isolation of the Arab minority from the Jewish population. Chief among these are Israel's government ministries and agencies that deal exclusively with Arab or Jewish affairs; a military organization from which most Moslem Arabs are excluded; Jewish political parties sponsoring "affiliated lists" of Arabs; Histadrut, a general union of workers which still refuses to allow Arabs entrance into positions of authority; the Jewish Agency and the Jewish National Fund, autonomous institutions channeling resources to the Jewish population for vocational training, economic development projects, land acquisition, and social services.

Given such conditions, Israel's Arab population has remained inordinately dependent on a Jewish-controlled economy. Arab laborers, Arab teachers, Arab civil servants, Arab politicians practically all are dependent on Jews for jobs. For many the threat of being blacklisted for speaking out against government policies is potent indeed.

In addition to lacking autonomous bases of economic power, Israel's Arabs have been further weakened by wholesale expropriations of their land, inadequate compensation programs, and discrimination in regard to the leasing of land. Additional measures have made it difficult if not impossible for them to overcome their political and cultural differences to the point of uniting to protect themselves from further exploitation. Among these are various internal obstacles utilized by Israeli authorities to maintain a perpetual state of fragmentation both within Arab communities and between Arab subcultures.

The situation as described here is far from encouraging. Under conditions of general mobilization against its Arab neighbors, the permissible level of Arab political activity in Israel is not likely to be raised appreciably. In fact, there are those who would argue (without in any way condoning specific acts of injustice) that political realities have severely limited the range of viable options available to government and institutional policymakers in their treatment of Arabs. Lustick might have given more attention to such considerations. Even so, Arabs in the Jewish State presents a sobering account of emotion-charged events, and as such it constitutes a useful survey in the field of Mideast studies.

Kenneth Libo, English-language editor for the Jewish Daily Forward, is co-author, with IrvingHowe, of World of Our Fathers and How We Lived: A Documentary History of Immigrant Jews in America.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTenure: an academic necessity

April 1981 By A. E. DeMaggio -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureTenure: the tragedy of the slaughterhouse

April 1981 By Peter W. Travis -

Cover Story

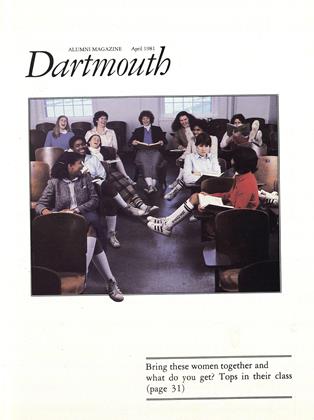

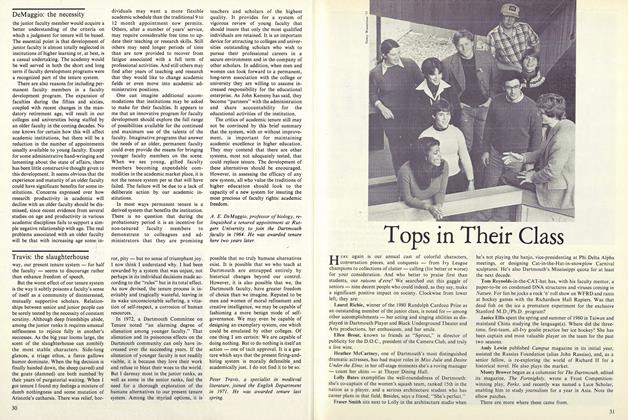

Cover StoryTops in Their Class

April 1981 -

Cover Story

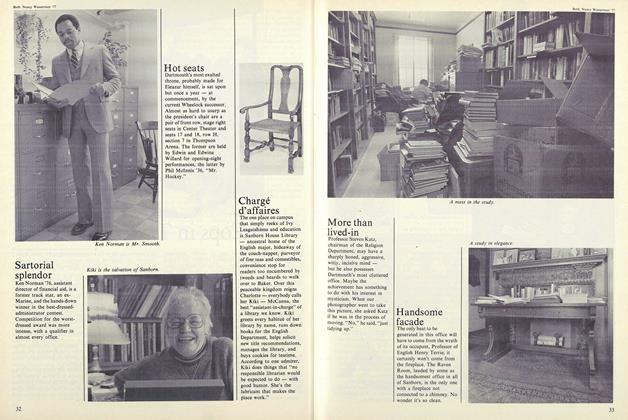

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Cover Story

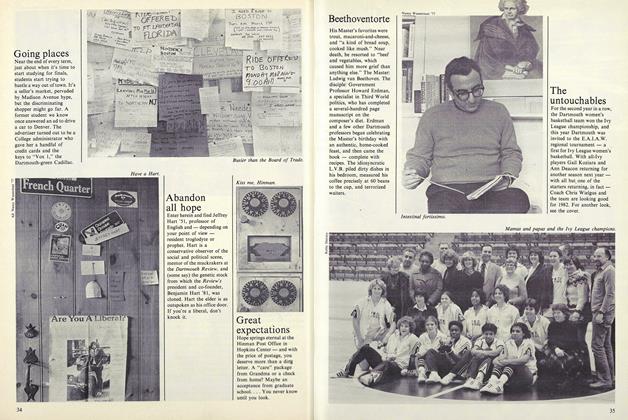

Cover StoryBeethoventorte

April 1981

Books

-

Books

BooksM. A. Donohue & Co

OCTOBER 1931 -

Books

BooksNORTHERN LIGHTS: WRITERS FROM THE UPPER VALLEY OF VERMONT AND NEW HAMPSHIRE.

June 1974 By CLAUDE G. LIMAN '65 -

Books

BooksSome Makers of American Literature

April 1924 By F. P. E. -

Books

BooksTHE DISENCHANTED,

December 1950 By JOSEPH A. MILLIMET '36 -

Books

BooksCOMMUNICATING WITH EMPLOYEES.

NOVEMBER 1963 By ROBERT H. GUEST -

Books

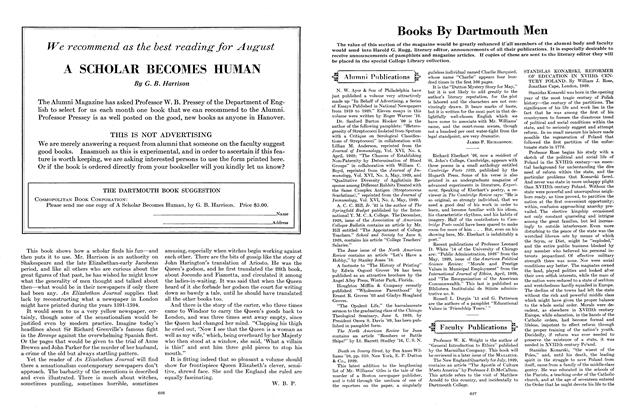

BooksSTANISLAS KONARSKI, REFORMER OF EDUCATION IN XVIIIth CENTURY POLAND

AUGUST 1929 By W. R. W.