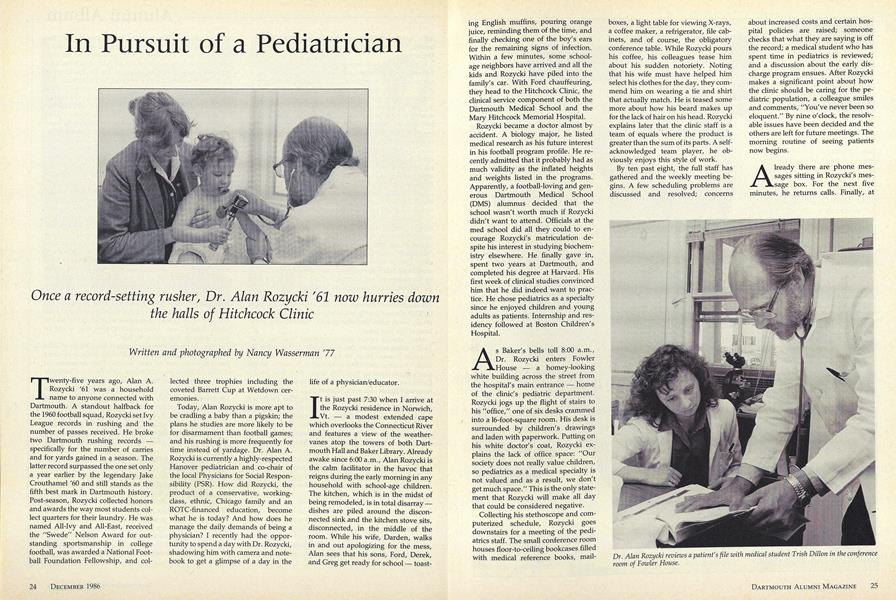

Once a record-setting rusher, Dr. Alan Rozycki '61 now hurries downthe halls of Hitchcock Clinic

Twenty-five years ago, Alan A. Rozycki '61 was a household name to anyone connected with Dartmouth. A standout halfback for the 1960 football squad, Rozycki set Ivy League records in rushing and the number of passes received. He broke two Dartmouth rushing records specifically for the number of carries and for yards gained in a season. The latter record surpassed the one set only a year earlier by the legendary Jake Crouthamel '60 and still stands as the fifth best mark in Dartmouth history. Post-season, Rozycki collected honors and awards the way most students collect quarters for their laundry. He was named All-Ivy and All-East, received the "Swede" Nelson Award for outstanding sportsmanship in college football, was awarded a National Football Foundation Fellowship, and collected three trophies including the coveted Barrett Cup at Wetdown ceremonies.

Today, Alan Rozycki is more apt to be cradling a baby than a pigskin; the plans he studies are more likely to be for disarmament than football games; and his rushing is more frequently for time instead of yardage. Dr. Alan A. Rozycki is currently a highly-respected Hanover pediatrician and co-chair of the local Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR). How did Rozycki, the product of a conservative, working- class, ethnic, Chicago family and an ROTC-financed education, become what he is today? And how does he manage the daily demands of being a physician? I recently had the opportunity to spend a day with Dr. Rozycki, shadowing him with camera and notebook to get a glimpse of a day in the life of a physician/educator.

It is just past 7:30 when I arrive at the Rozycki residence in Norwich, Vt. a modest extended cape which overlooks the Connecticut River and features a view of the weathervanes atop the towers of both Dartmouth Hall and Baker Library. Already awake since 6:00 a.m., Alan Rozycki is the calm facilitator in the havoc that reigns during the early morning in any household with school age children. The kitchen, which is in the midst of being remodeled, is in total disarray dishes are piled around the disconnected sink and the kitchen stove sits, disconnected, in the middle of the room. While his wife, Darden, walks in and out apologizing for the mess, Alan sees that his sons, Ford, Derek, and Greg get ready for school toasting English muffins, pouring orange juice, reminding them of the time, and finally checking one of the boy's ears for the remaining signs of infection. Within a few minutes, some school age neighbors have arrived and all the kids and Rozycki have piled into the family's car. With Ford chauffeuring, they head to the Hitchcock Clinic, the clinical service component of both the Dartmouth Medical School and the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital.

Rozycki became a doctor almost by accident. A biology major, he listed medical research as his future interest in his football program profile. He recently admitted that it probably had as much validity as the inflated heights and weights listed in the programs. Apparently, a football loving and generous Dartmouth Medical School (DMS) alumnus decided that the school wasn't worth much if Rozycki didn't want to attend. Officials at the med school did all they could to encourage Rozycki's matriculation despite his interest in studying biochemistry elsewhere. He finally gave in, spent two years at Dartmouth, and completed his degree at Harvard. His first week of clinical studies convinced him that he did indeed want to practice. He chose pediatrics as a specialty since he enjoyed children and young adults as patients. Internship and residency followed at Boston Children's Hospital.

As Baker's bells toll 8:00 a.m., Dr. Rozycki enters Fowler House a homey-looking white building across the street from the hospital's main entrance home of the clinic's pediatric department. Rozycki jogs up the flight of stairs to his "office," one of six desks crammed into a 16-foot-square room. His desk is surrounded by children's drawings and laden with paperwork. Putting on his white doctor's coat, Rozycki explains the lack of office space: "Our society does not really value children, so pediatrics as a medical specialty is not valued and as a result, we don't get much space." This is the only statement that Rozycki will make all day that could be considered negative.

Collecting his stethoscope and computerized schedule, Rozycki goes downstairs for a meeting of the pediatrics staff. The small conference room houses floor-to-ceiling bookcases filled with medical reference books, mailboxes, a light table for viewing X-rays, a coffee maker, a refrigerator, file cabinets, and of course, the obligatory conference table. While Rozycki pours his coffee, his colleagues tease him about his sudden notoriety. Noting that his wife must have helped him select his clothes for the day, they commend him on wearing a tie and shirt that actually match. He is teased some more about how his beard makes up for the lack of hair on his head. Rozycki explains later that the clinic staff is a team of equals where the product is greater than the sum of its parts. A self acknowledged team player, he obviously enjoys this style of work. By ten past eight, the full staff has gathered and the weekly meeting begins. A few scheduling problems are discussed and resolved; concerns about increased costs and certain hospital policies are raised; someone checks that what they are saying is off the record; a medical student who has spent time in pediatrics is reviewed; and a discussion about the early discharge program ensues. After Rozycki makes a significant point about how the clinic should be caring for the pediatric population, a colleague smiles and comments, "You've never been so eloquent." By nine o'clock, the resolvable issues have been decided and the others are left for future meetings. The morning routine of seeing patients now begins.

Already there are phone messages sitting in Rozycki's message box. For the next five minutes, he returns calls. Finally, at 9:15, he sees his first patient, a teenager in need of a medical check-up certificate to complete her application for a summer exchange program. After explaining why he is being followed by a photographer, he gets on with the business at hand. The two, doctor and patient, sit in street clothes discussing school, family, social life, health concerns, and general well being. Rozycki asks about everything from what the woman does in her free time to how regularly she wears seat belts. After asking about dates, he confirms that she knows about contraception. Finally, it is time for the physical exam. While the patient changes into a dressing gown, Rozycki returns some new phone calls and then returns with a nurse to do the exam.

About five or ten minutes later, he is back in the hallway, completing the paperwork and ready to head into another examining room. Awaiting him is a six-month-old baby with cold-related respiratory problems. Rozycki discusses the baby's symptoms and similar problems encountered by the baby's older brother with the child's mother, while the child sits on the lap of his grandmother. As he conducts the physical exam, Rozycki begins his constant and very genuine banter: "What a great-looking baby! Aren't you lucky to have both your mom and grandma here with you? Let's take a look here what a great smile. OK, little fellow, time to stand up." Within seconds, or so it seems, he diagnoses an ear infection, checks that the mother is familiar with how to administer the medication, and writes a prescription. As we leave the examining room, he returns yet another call.

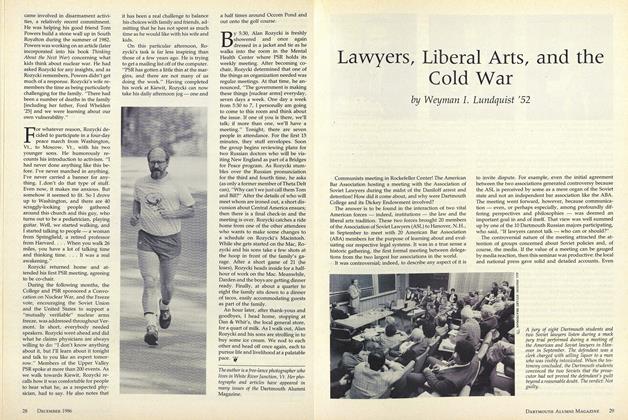

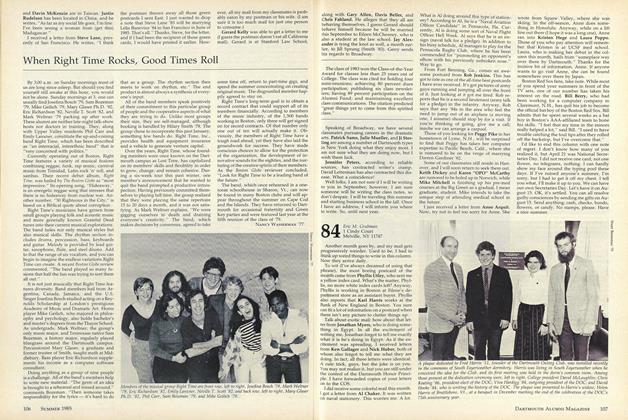

Pediatric resident Mark Kopper catches Rozycki and seeks his advice about the patient he is examining. All of the pediatricians working at the clinic rotate the tasks of providing consultation to other physicians or assistants and supervising the pediatric medical students. This morning, Rozycki has been assigned both. The two doctors go to the conference room and discuss Kopper's concern that the child in question might have tonsilitis. They both return to see the patient. As Rozycki examines the child, he explains what he is finding in medical terms to Kopper. After indicating to Kopper that he was right to be concerned, Rozycki turns to the mother and explains their con It is now 10:30. Two new families have filled the examining rooms, and Trish Dillon, a third-year student at the medical school, has arrived to spend the day. In the conference room, Rozycki and Dillon review the files on one of the patients. She goes to one room to get initial information on that patient, while he sees the other family across the hall a four-day-old baby and his mother. The curious, lighthearted questioning begins immediately. "Congratulations. How was the delivery? When did you go home? What does his daddy think of him?" followed by the familiar Rozycki monologue, "Aren't you a handsome little fellow? Don't you look great." Sufficiently complimented, the young lad relieves himself in Rozycki's direction. Noting, with a grin, that this is why doctors wear white coats, Rozycki adds, "You little cuss," followed again by the more positive banter. Dillon interrupts the exam to check with Rozycki. Apologizing as he leaves, Rozycki stops in the hallway to discuss the particulars of an apparent ear infection. Entering the room, he examines the sick youngster on his mother's lap, then performs the same ritual on his well-behaved older brother. The two student and experienced doctor concur on the diagnosis, and Rozycki scribbles out a prescription.

Returning to the tiny new baby, Rozycki remembers an exercise in medical school where he observed a newborn for the first 24 hours of her life. He shows us how the child he is seeing has assumed what is called the "fencing position," commenting that "these first hours of a child's life are when they are observing and learning at an incredibly intense pace." Then, there is a return to information gathering. Rozycki phrases his questions so as to preclude value judgments. Mom is asked, "Do you work outside the home?" and "What's his daddy do?" Rozycki's patients throughout the Upper Valley comment favorably and willingly on his demeanor and caring.

The morning continues in a similar fashion more patients, consultations, paperwork, and phone calls. By half past noon, I am exhausted. I promise myself that I will never again complain about waiting in a cold examining room for the doctor to appear. It is close to 1:30 by the time Rozycki finishes seeing his "morning" patients. He has seen 11 different patients along with their brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, and grandmothers. He has given parents encouragement and advice about the challenges of parenting ("half this job is psychology," he will admit later), written a half dozen prescriptions, and attempted to comfort a couple of crying youngsters. He has consulted twice each with the pediatric resident and the physician's assistant. In addition, he has returned at least 20 calls.

Since it is Tuesday, Rozycki has the afternoon "off." He grabs a cup of coffee and a few cookies for lunch. For the next hour Rozycki dons his role as Director of the DMS Alumni Fund and meets in a private session with the Medical School's Assistant Director of Capital Giving to review plans for a special development project.

At 2:30, Rozycki switches his Medical School folders for those concerned with Physicians for Social Responsibility and heads to Kiewit Computer Center. Rozycki explained how he became involved in disarmament activities, a relatively recent commitment. He was helping his good friend Tom Powers build a stone wall up in South Royalton during the summer of 1982. Powers was working on an article (later incorporated into his book ThinkingAbout the Next War) concerning what kids think about nuclear war. He had asked Rozycki for any insights, and as Rozycki remembers, Powers didn't get much of a response. Rozycki's wife remembers the time as being particularly challenging for the family. "There had been a number of deaths in the family [including her father, Ford Whelden '25] and we were learning about our own vulnerability."

For whatever reason, Rozycki decided to participate in a four-day peace march from Washington, Vt., to Moscow, Vt., with his two younger sons. He humorously recounts his introduction to activism. "I had never done anything like this before. I've never marched in anything. I've never carried a banner for anything. I don't do that type of stuff. Even now, it makes me anxious. But somehow it seemed to fit. So I drove up to Washington, and there are 40 scraggly-looking people gathered around this church and this guy, who turns out to be a pediatrician, playing guitar. Well, we started walking, and I started talking to people a woman from Springfield, a retired professor from Harvard. . . . When you walk 26 miles, you have a lot of talking time and thinking time. ... It was a real awakening."

Rozycki returned home and attended his first PSR meeting, agreeing to be co-chair.

During the following months, the College and PSR sponsored a Convocation on Nuclear War, and the Freeze vote, encouraging the Soviet Union and the United States to support a "mutually verifiable" nuclear arms freeze, was addressed throughout Vermont. In short, everybody needed speakers. Rozycki went ahead and did what he claims physicians are always willing to do: "I don't know anything about it, but I'll learn about it tonight and talk to you like an expert tomorrow." Members of the Upper Valley PSR spoke at more than 200 events. As we walk towards Kiewit, Rozycki recalls how it was comfortable for people to hear what he, as a respected physician, had to say. He also notes that it has been a real challenge to balance his choices with family and friends, admitting that he has not spent as much time as he would like with his wife and kids.

On this particular afternoon, Rozycki's task is far less inspiring than those of a few years ago. He is trying to get a mailing list off of the computer. "PSR has gotten a little thin at the margins, and there are not many of us doing the work." Having completed his work at Kiewit, Rozycki can now take his daily afternoon jog one and a half times around Occom Pond and out onto the golf course.

By 5:30, Alan Rozycki is freshly showered and once again dressed in a jacket and tie as he walks into the room in the Mental Health Center where PSR holds its weekly meeting. After becoming co-chair, Rozycki determined that one of the things an organization needed was regular meetings. At that time, he announced, "The government is making these things [nuclear arms] everyday, seven days a week. One day a week from 5:30 to 7, I personally am going to come to this room and think about the issue. If one of you is there, we'll talk; if more than one, we'll have a meeting." Tonight, there are seven people in attendance. For the first 15 minutes, they stuff envelopes. Soon the group begins reviewing plans for two Russian doctors who will be visiting New England as part of a Bridges for Peace program. As Rozycki stumbles over the Russian pronunciation for the third and fourth time, he asks (as only a former member of Theta Delt can), "Why can't we just call them Tom and Bill?" After the details of who will meet whom are ironed out, a short discussion about Central America ensues; then there is a final check-in and the meeting is over. Rozycki catches a ride home from one of the other attendees who wants to make some changes to a schedule on Rozycki's Macintosh. While she gets started on the Mac, Rozycki and his sons take a few shots at the hoop in front of the family's garage. After a short game of 21 (he loses), Rozycki heads inside for a half-hour of work on the Mac. Meanwhile, Darden and the boys are getting dinner ready. Finally, at about a quarter to eight the family sits down to a dinner of tacos, easily accommodating guests as part of the family.

An hour later, after thank-yous and goodbyes, I head home, stopping at Dan & Whit's, the local general store, for a quart of milk. As I walk out, Alan Rozycki and his sons are strolling in to buy some ice cream. We nod to each other and head off once again, each to pursue life and livelihood at a palatable pace.

Dr. Alan Rozycki reviews a patient's file with medical student Trish Dillon in the conferenceroom of Fowler House.

cerns, reassuring her that, in this case, it is not tonsilitis.

The author is a free-lance photographer wholives in White River Junction, Vt. Her photographs and articles have appeared inmany issues of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLawyers, Liberal Arts, and the Cold War

December 1986 By Weyman I. Lundquist '52 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Hovey: The Incomplete Arthurian

December 1986 By Daniel P. Nastali -

Feature

FeatureSnowmaking at the Dartmouth Skiway: Taking the Wonder Out of Winter

December 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleMarianne Alverson: At home in many worlds

December 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

ArticleHarold Sack '32: A master of pieces of the past

December 1986 By Rex Roberts -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

December 1986 By C. E. Widmayer

Nancy Wasserman '77

-

Article

ArticleBackstairs and Blooms

April 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWearers of the Green

OCTOBER 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleTimothy Sheyda '72: Providing Food for Thought

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWhen Right Time Rocks, Good Times Roll

June • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

DECEMBER • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Sports

SportsWhitewater Weekend

June 1987 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Features

-

Feature

FeatureVincent Starzinger Professor of Government 1,000 miles in o single scull

January 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCOMMENCEMENT

June • 1985 -

Feature

FeatureWORDS AND PICTURES MARRIED The Beginnings of DR.SEUSS

April 1976 By Edward Connery Lathem -

FEATURE

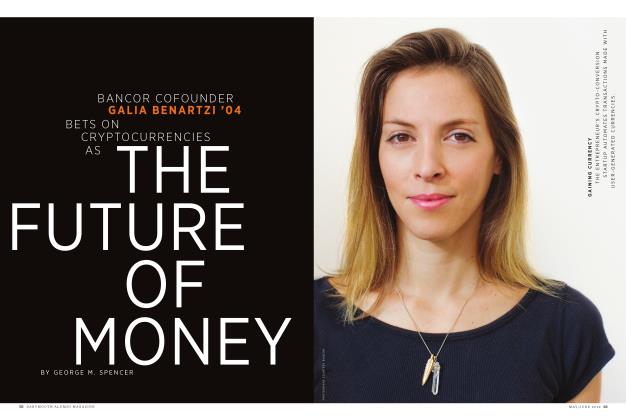

FEATUREThe Future of Money

MAY | JUNE 2019 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

COVER STORY

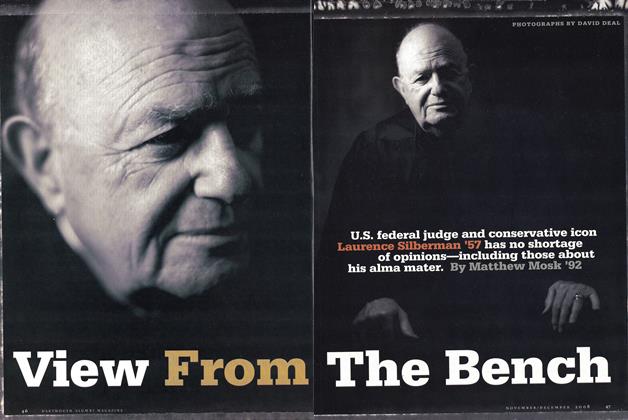

COVER STORYView From the Bench

Nov/Dec 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

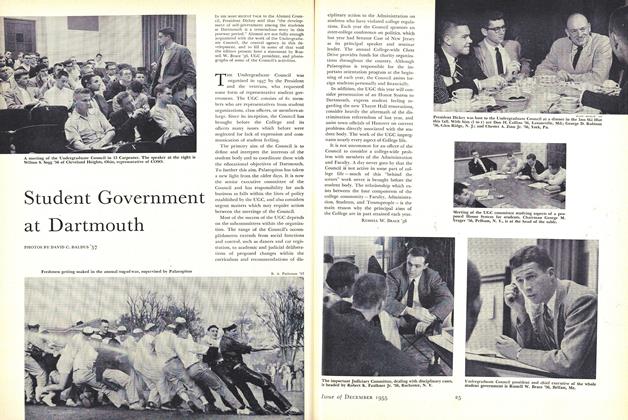

FeatureStudent Government at Dartmouth

December 1955 By RUSSELL W. BRACE '56