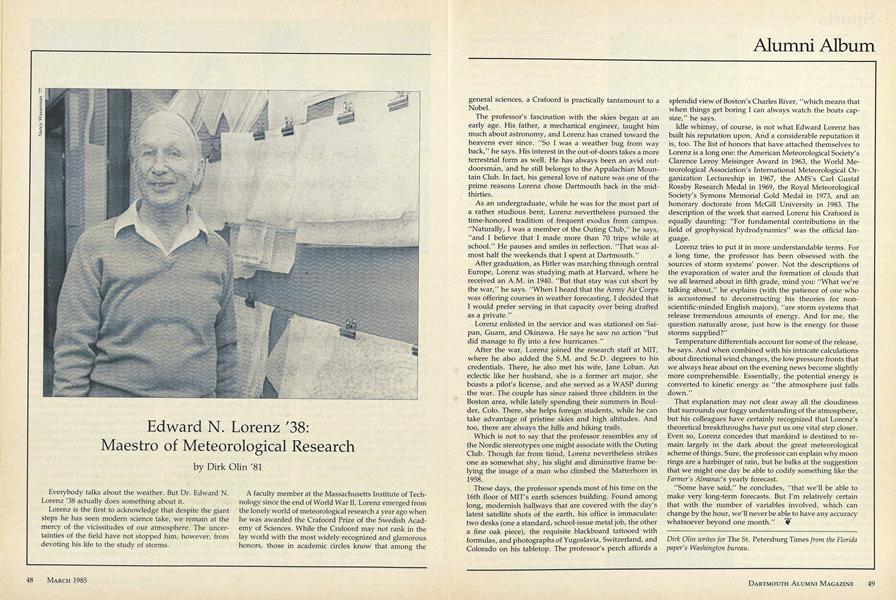

Everybody talks about the weather. But Dr. Edward N. Lorenz '38 actually does something about it.

Lorenz is the first to acknowledge that despite the giant steps he has seen modern science take, we remain at the mercy of the vicissitudes of our atmosphere. The uncertainties of the field have not stopped him, however, from devoting his life to the study of storms.

A faculty member at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology since the end of World War II, Lorenz emerged from the lonely world of meteorological research a year ago when he was awarded the Crafoord Prize of the Swedish Academy of Sciences. While the Crafoord may not rank in the lay world with the most widely-recognized and glamorous honors, those in academic circles know that among the general sciences, a Crafoord is practically tantamount to a Nobel.

The professor's fascination with the skies began at an early age. His father, a mechanical engineer, taught him much about astronomy, and Lorenz has craned toward the heavens ever since. "So I was a weather bug from way back," he says. His interest in the out-of-doors takes a more terrestrial form as well. He has always been an avid outdoorsman, and he still belongs to the Appalachian Mountain Club. In fact, his general love of nature was one of the prime reasons Lorenz chose Dartmouth back in the midthirties.

As an undergraduate, while he was for the most part of a rather studious bent, Lorenz nevertheless pursued the time-honored tradition of frequent exodus from campus. "Naturally, I was a member of the Outing Club," he says, "and I believe that I made more than 70 trips while at school." He pauses and smiles in reflection. "That was almost half the weekends that I spent at Dartmouth."

After graduation, as Hitler was marching through central Europe, Lorenz was studying math at Harvard, where he received an A.M. in 1940. "But that stay was cut short by the war," he says. "When I heard that the Army Air Corps was offering courses in weather forecasting, I decided that I would prefer serving in that capacity over being drafted as a private."

Lorenz enlisted in the service and was stationed on Sai- pan, Guam, and Okinawa. He says he saw no action "but did manage to fly into a few hurricanes."

After the war, Lorenz joined the research staff at MIT, where he also added the S.M. and Sc.D. degrees to his credentials. There, he also met his wife, Jane Loban. An eclectic like her husband, she is a former art major, she boasts a pilot's license, and she served as a WASP during the war. The couple has since raised three children in the Boston area, while lately spending their summers in Boulder, Colo. There, she helps foreign students, while he can take advantage of pristine skies and high altitudes. And too, there are always the hills and hiking trails.

Which is not to say that the professor resembles any of the Nordic stereotypes one might associate with the Outing Club. Though far from timid, Lorenz nevertheless strikes one as somewhat shy, his slight and diminutive frame belying the image of a man who climbed the Matterhorn in 1958.

These days, the professor spends most of his time on the 16th floor of MlT's earth sciences building. Found among long, modernish hallways that are covered with the day's latest satellite shots of the earth, his office is immaculate: two desks (one a standard, school-issue metal job, the other a fine oak piece), the requisite blackboard tattooed with formulas, and photographs of Yugoslavia, Switzerland, and Colorado on his tabletop. The professor's perch affords a splendid view of Boston's Charles River, "which means that when things get boring I can always watch the boats capsize he says.

Idle whimsy, of course, is not what Edward Lorenz has built his reputation upon. And a considerable reputation it is, too. The list of honors that have attached themselves to Lorenz is a long one: the American Meteorological Society's Clarence Leroy Meisinger Award in 1963, the World Meteorological Association's International Meteorological Organization Lectureship in 1967, the AMS's Carl Gustaf Rossby Research Medal in 1969, the Royal Meteorological Society's Symons Memorial Gold Medal in 1973, and an honorary doctorate from McGill University in 1983. The description of the work that earned Lorenz his Crafoord is equally daunting: "For fundamental contributions in the field of geophysical hydrodynamics" was the official language.

Lorenz tries to put it in more understandable terms. For a long time, the professor has been obsessed with the sources of storm systems' power. Not the descriptions of the evaporation of water and the formation of clouds that we all learned about in fifth grade, mind you: "What we're talking about," he explains (with the patience of one who is accustomed to deconstructing his theories for nonscientific-minded English majors), "are storm systems that release tremendous amounts of energy. And for me, the question naturally arose, just how is the energy for those storms supplied?"

Temperature differentials account for some of the release, he says. And when combined with his intricate calculations about directional wind changes, the low pressure fronts that we always hear about on the evening news become slightly more comprehensible. Essentially, the potential energy is converted to kinetic energy as "the atmosphere just falls down."

That explanation may not clear away all the cloudiness that surrounds our foggy understanding of the atmosphere, but his colleagues have certainly recognized that Lorenz's theoretical breakthroughs have put us one vital step closer. Even so, Lorenz concedes that mankind is destined to remain largely in the dark about the great meteorological scheme of things. Sure, the professor can explain why moon rings are a harbinger of rain, but he balks at the suggestion that we might one day be able to codify something like the Farmer's Almanac's yearly forecast.

"Some have said," he concludes, "that we'll be able to make very long-term forecasts. But I'm relatively certain that with the number of variables involved, which can change by the hour, we'll never be able to have any accuracy whatsoever beyond one month."

Dirk Olin writes for The St. Petersburg Times from the Floridapaper's Washington bureau.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

March 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY EVOLUTION?

March 1985 By Warren D. Allmon '82 -

Feature

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

March 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Sports

SportsRecruiters' haul

March 1985 By Jim Kenyan -

Article

ArticleDynamite

March 1985 By Alice Dragoon '86 -

Article

ArticleRandom Thoughts

March 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85

Dirk Olin '81

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

OCTOBER 1991 -

Feature

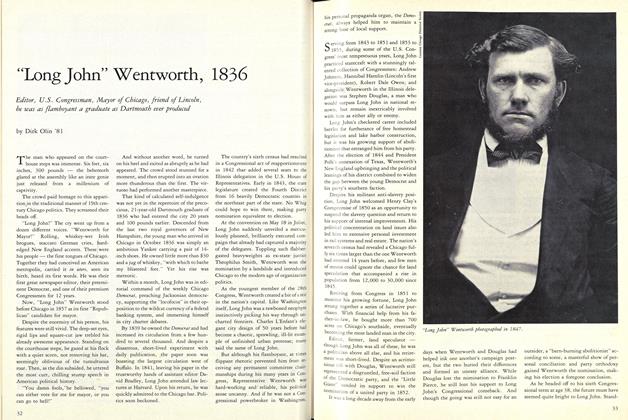

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

MARCH 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Article

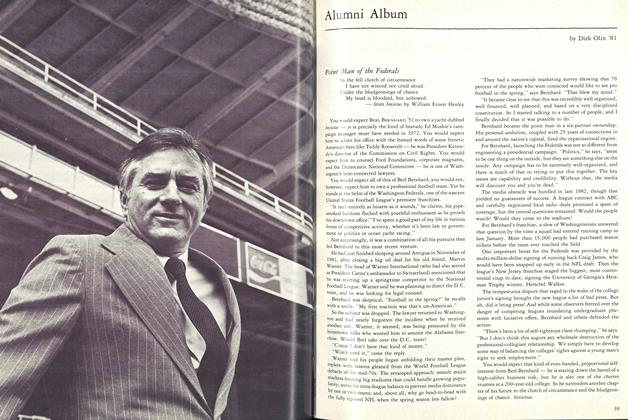

ArticleAlumni Album

APRIL 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Interviews

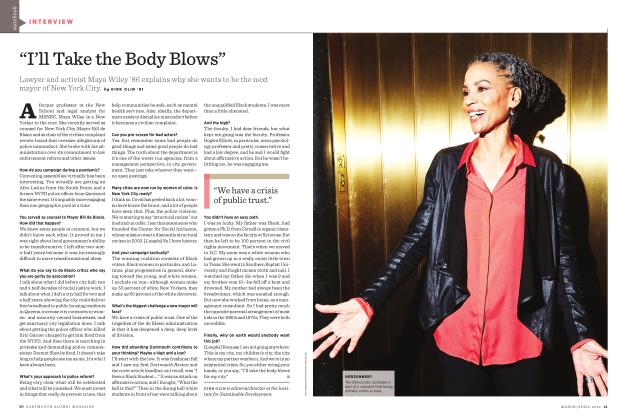

Interviews“I’ll Take the Body Blows”

MARCH | APRIL 2021 By DIRK OLIN '81 -

Voices in the Wilderness

Voices in the WildernessOrder in the Court

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By Dirk Olin '81

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH SONG

December, 1908 -

Article

ArticleHistory Test Results

March 1943 -

Article

Article$128,947 Over Fund Goal

OCTOBER 1963 -

Article

ArticleIndian Youth Conference

JANUARY 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate

December 1946 By Charles Clucas '44 -

Article

ArticleI. WANT. YOU. TO.

September | October 2013 By DANIYAL MUEENUDDIN