Peter Fox Smith can elaborate on the relationship between art and theology in Wagnerian opera as easily as he can instruct young women in the grace of putting the shot. He does both regularly. At Leverone field house you can hear the mellifluous tones of his well-educated voice urging on the young women he works with as coach of the Dartmouth women's track teams. You can hear the same tones on Vermont Public Radio's "Saturday Afternoon at the Opera," which Smith hosts. This gray-bearded and balding embodiment of the Greek ideal of developing both Hind and body has the added distinction of having been on the Harvard faculty.

In 1970, while serving Harvard as assistant director of general education and professor of independent studies, Smith realized that the administrative problems generated by the activism of the late sixties were taking greater and greater amounts of his time, leaving less and less for teaching, his self-professed passion. At that time, with 12 years of "intensive teaching" behind him, he made the decision that where he lived was more important than what he did and opted to return himself and his family to the country in this instance, Vermont. During the next seven years, he held a variety of positions, including two years as director of the Vermont Council on the Arts. In 1977, he had decided to free-lance, when he saw an ad for the position of women's track coach at Dartmouth. He had run the half-mile, 440s, relays, and some cross-country during his college and high school years and also participated in some field events. He had also coached at Woodstock Union High School while his own children ran track. Smith applied for and received the then part-time position.

Since 1977, the caliber, commitment, and coaching demands of the track teams have expanded at an extraordinary pace. There are now three coaches for a sport that swells during the outdoor season to almost 40 women. The quality of entering students has also improved dramatically because of better recruiting and of a marked improvement in high school track programs as a result of Title IX. Dartmouth has always been attractive to distance runners because of its rural location, and Smith and his assistants have made sure that coaches throughout New England and other key regions know about the Dartmouth program and about Smith's willingness to answer the inquiries of anyone who could be competitive in the Dartmouth admissions process.

During the track program's early years, Smith found himself teaching many women the basics of running. As he explained, "Many people don't run properly. You need to assess your anatomical structure to determine what part of the foot to land on. You also need to know how to use: your arms and upper body and how to relax while putting forth energy." Although most women going out for track these days have these basics under control, Smith is still called upon to teach them to women from other athletic teams. Even so, says Smith, "I could not be lured away to coach the men's team. It is a marvelous sight to see a young woman take off her bracelets and her earrings, put on her running shoes, go out and run her legs off and die before she'll let somebody beat her and then come in, take a shower, and there she is, a full 100 per cent feminine creature, all over again."

Smith's record is so successful that the College would not want him to change his position either. His teams have captured 13 Ivy championships in the last six years, and his 1982 cross-country team defeated 31 of the 39 teams it raced. The harriers also took an upset third at the regional qualifier after being slated to place eighth. While Smith is rightly proud of his champions, he is neither a workhorse nor someone driven to create exceptional win-loss records. As the brochure describing the women's track program clearly states, "Aspirants should understand that whatever their talent, they make the squad if they commit themselves to regular training and doing their best. The program provides a home for both young women seeking a vigorous and competitive break from academic rigors and those seeking competition on the highest possible levels."

Track practices involve a lot of work, an equal amount of good-natured teasing, and a bit of chaos. Smith tries to create a "mood totally other than the intense academic experience." During a typical practice in Leverone, Smith will simultaneously watch and time his long-distance runners on one workout, time his middledistance runners working on intervals, and watch the baton-practice being coached by his assistant, Art McKinnon. In the midst of all this, he will chat with one woman about which event she wants to run in the upcoming meet, cheer on some men practicing on the inside lanes, tease quite a few women about their boy friends, and help a runner figure out what her time was relative to the lane in which she was running. During the afternoon he will also find time to step off to a quiet corner to lend a respectful ear to a team member who is discouraged. In addition, he will check out the varied illnesses and sprains that can hamper his team, being careful to keep his overzealous competitors from taking on too much too fast.

The women competitors see Smith's concern almost immediately. As one experienced freshman commented, "He's wonderful. He knew everyone's name by the second day, something that's important in building a team feeling, and he takes an interest in everyone. You know he's pushing for you." During the cross- country season, Smith frequently trains with the team, providing an important psychological boost during tough practices.

Peter Fox Smith sits in his Alumni Gym office, behind his oak desk, looking more like a professor than a coach. Wearing the quintessential academic uniform - Oxford shirt, conservative tie, knitted Ragg vest, and corduroy slacks he offers tea to his visitors. Only his Nike running shoes and the track posters and photos on the walls indicate that he is a coach. Smith comments, "I am basically a teacher. I don't think of coaching as having given up something. I've just changed the subject matter from philosophy to distance running." However, he still does a bit of more traditional teaching by lecturing throughout New England on opera and nineteenth-century philosophy. He recently delivered his twelfth annual Richard Wagner lecture at Exeter Academy.

And there's the radio teaching, too. Each Saturday afternoon, via delayed broadcast, Smith teaches Vermont Public Radio listeners to appreciate the intrigues, styles, and masters of the opera. Many a listener has discovered the joy of opera through Smith's careful and precise explanations. A longtime lover of radio, Smith confessed to listening to a portable radio between the sheets as a child, long after he should have been asleep. "There is an intimacy and mystery with regard to the radio that does not exist in other forms of mass media," he explains. Smith's fascination with the opera also began as a child; he was constantly exposed to music through his father, a professional singer. This attachment was cemented after listening to Richard Wagner's complete Ring Cycle for 16 hours while he was a graduate student at Harvard. Ideas generated during that uninterrupted listening served as the basis for Smith's doctoral dissertation concerning art and religion in Wagner's work.

In between the demands of volunteering at Vermont Public Radio and coaching the track teams, Smith finds time to work his North Pomfret farm. He and his wife garden-extensively and raise some animals. The notoriously bemused and ignorant sheep are Smith's current passion. He is determined to cross the Suffolk Blackface with the long-haired Romney. Undoubtedly, he will pursue this new endeavor with his characteristic enjoyment, vigor, passion - and success.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

March 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

Feature

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

March 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

March 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

March 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Article

ArticleSetting the Record Straight: A Senior-Year Perspective

March 1983 By Libby Schmeltzer '83 -

Sports

SportsSports

March 1983 By Brad Hills '65

Nancy Wasserman '77

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1978 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorOn Wise Teachers

February 1992 -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

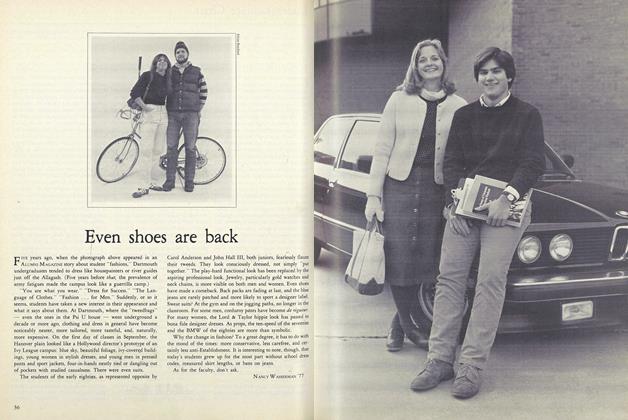

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

DECEMBER 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleToys in the Office

MARCH 1982 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureGet a Job

NOVEMBER 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77