"Mary Sue Glosser? Mary Sue Glosser is a bobby-dazzler, that's what Mary Sue Glosser is." British-born Peter Smith, former Hopkins Center director, translates his Lancashire term this way: "A bobbydazzler is someone who shines at what she does, someone who has a particular and contagious combination of ability, energy, and style."

Glosser is a small woman, deceptively fragile to look at. Her dark eyes meet yours with arresting simplicity, and the quiet intensity with which she discusses her work draws you like a magnet into the world of magical experiences that she orchestrates from her offices in Carpenter Hall. As curator of the College's Arts Education Services (a function of the Hopkins Center/Hood Museum complex), Glosser daily pulls a myriad of strings to keep a complex set of programs in operation for the benefit of the schoolchildren of the Upper Valley 27,000 of them last year.

An art historian from Illinois, Glosser came to Dartmouth from a position at the Peabody Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, where she was administrator for the educational department. She specializes in the interpretation of visual arts, and she finds the interdisciplinary richness of Dartmouth's resources in the visual and performing arts tremendously exciting. "There are 500 to 700 events a year at the Hop, and combining that resource with resident artists and faculty in the arts and a wonderful library and a first-rate museum effort is a great opportunity," she says. The situation frees her, she feels, to try almost anything: "There's always some check on what I'm doing, some authority around to let me know if I'm misinterpreting something. That's a wonderful resource.

The efforts of the Hop to reach out to the area's children have venerable roots its first director, Warner Bentley, was always delighted to see the yellow buses pull up, and he saw to it that there was always something special for children at Christ mas time. Nothing formal transpired, however, until 1971, when Peter Phillips '71, a conscientious objector, sold the idea of a Hopkins Center outreach program first to a funding agency and then (as alternative service) to the U.S. Army.

"At its most bullish," recalls Smith, "the Outreach program went beyond the schools to include special audiences, local prisons, and hospitals. It has become the most extensive program of its kind among private colleges, certainly in this part of the country, and probably in the country as a whole. The National Endowment for the Arts is very enthusiastic about it they call it a model program."

"It used to be drop-kick," explains Glosser in describing recent changes in Outreach, which has been rechristened Arts Education Services. "There would be a special exhibit of, say, watercolors, at the Hop and we might get several schools to visit or we might hire a watercolorist to go around to various schools and give demonstrations. But now we have a much deeper interest in developmental outreach." She explains how vital and inspiring it is to link up many aspects social history, studio arts, visual arts, performing arts, participatory workshops into an exciting, wide-ranging experience of art as it functions in culture. It delights her to combine, for instance, a children's workshop by an African dance troupe with both the troup's professional performance and a second-grade class in African mask-making taught by professional artists.

Money, explains Glosser predictably, is her one real problem. Half of her budget is "soft" money, and she spends a lot of her time juggling for funds. "The Friends of the Hop have been crucial," she says. They're the ones who have always budgeted for development in the arts for transportation subsidies for the schools, for instance.' Glosser describes in poignant detail the plight of some money-strapped Upper Valley schools that want to take advantage of her services but cannot afford even the minimal, subsidized fees she must charge. "It was a matter of seven dollars once," she says, wincing, and confesses that that time she couldn't bear it and donated the seven dollars from a discretionary fund.

Overseeing the development and implementation of arts-related programs that serve 97 private and public schools in Vermont and New Hampshire located within a 150-mile radius of Hanover keeps Glosser running. She hires professional artists to teach monthly classes for participating schoolchildren of all ages, persuades performers booked by the Hop to give workshops for children and for their teachers, organizes puppet theater, children's films, grade-school photography workshops, special tours of Hop exhibits, secondgrade workshops with weavers-in-resi-dence, master classes in dance, Art with Basics classes oriented around objects from the Hood, workshops in art education for elementary teachers, shepherded daytrips to historic Boston and to the Vatican exhibition in New York the list is amazing.

Until the new Hood Museum is completed, Glosser and her staff will continue in their make-shift quarters in Carpenter Fine Arts building, in a small studio that is usually full of school children. "We sometimes pump 1,000 students through by 1:00 o'clock," laughs Glosser.

She has chosen her artist-teachers carefully they share her genuine enthusiasm for opening doors in the arts for the young. The first-grade class in paper-making is not just a dry demonstration of the techniques of making paper slurry, lifting it on screens, and drying it between felts. Vibrant young painter Kathleen Smith starts the class by discussing a Japanese elm-bark robe on loan from the Hood. She has the children recall their last month's lesson on China. They discuss differences and similarities between China and Japan, with maps, and move on to look at other things Japanese from the Hood, including intricate paper stencils and the fabrics printed from them. The youngsters participate avidly, guessing what the robe is made of, offering accounts of a big brother's trip to Japan, speculating about what the Japanese wrote on before they had paper, and learning about how highly the Japanese, unlike Americans, value paper as an art form.

Then Smith mixes the cotton pulp in the vat of water and lets the children slosh it around. She shows them the simple process of submerging a screen and lifting it coated with paper. They learn to sponge off excess water and how to peel the soggy sheet from the screen. Placed between wool felts and pressed under bricks, the paper they make, Smith promises, will dry and be mailed out to their school in a few days. She tells the youngsters a Japanese story and shows them how to make special Japanese designs based on the story, and while eight of the ten youngsters make designs, two at a time come up to the paper-making vat, where each child in the class makes a piece of paper. They have to be shooed out of the studio when their hour is up.

For the older children, Glosser provides the sparkling talents of professional artist Gretchen Cochran, whose classes are half an hour longer and involve sustained exercises in drawing and painting and printing and collage. Surrounded by superrealist paintings on loan from the Hood, one of Cochran's classes discusses superrealism and plays with ways of distorting images to make them reflect a heightened "reality." Several stuffed birds from the local science museum serve as their models, and each student draws one of the birds several times, each time exaggerating some single aspect. As her students ponder their birds intently, Cochran explains her personal purpose in arts education: "Most Americans draw at a third- or fourth-grade level. Ours is not a visual culture, and it doesn't foster continued skill in seeing and drawing. Everybody knows that he or she can draw through the third grade, but after that something happens, there is a crisis of confidence about drawing, and the skill atrophies. What I want to do is guide them safely through the crisis so they will always be able to draw."

The thing about her work that has pleased her most, says Glosser, is the tremendous change she has seen in herself, a growth that has come out of the experience of seeing other people's creative development, of seeing how other people see as they experience the programs she provides. "Learning what it is that a secondgrader needs to know helps me to understand what needs to be taught at all levels," she explains, leaning forward in a way that brings the bright, compassionate eyes into play with the soft, intense voice.

There is about her a rich and almost Oriental calmness, a reflection, perhaps, of her studies of the fabled Japanese tea ceremony. A Japanese woman she met at the Peabody Museum became, she explains, her "Japanese grandmother," and taught her, through the minute and carefully-observed rituals of the tea ceremony, how to learn. "Japanese etiquette," says Glosser, "is always to do one thing more, to look one time more. You learn to see that way."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni College Retrospective

May 1983 By Jean Dalury -

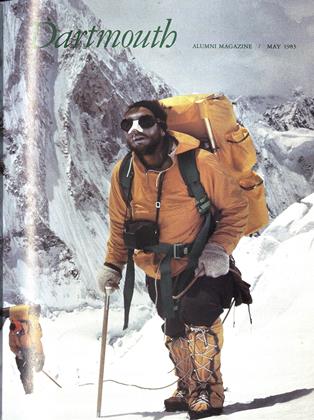

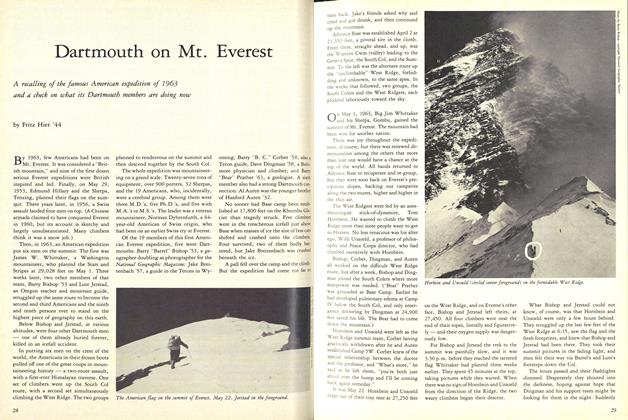

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mt. Everest

May 1983 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

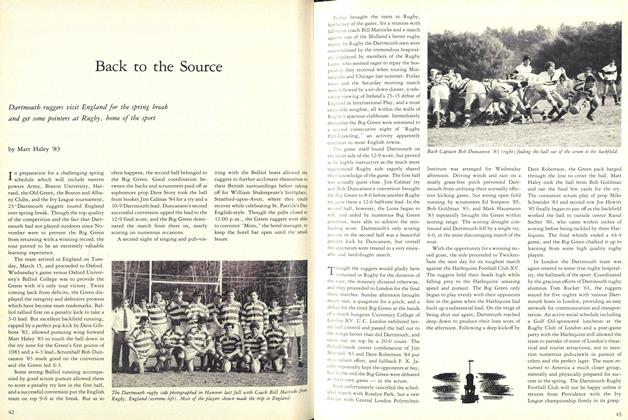

FeatureBack to the Source

May 1983 By Matt Haley '83 -

Cover Story

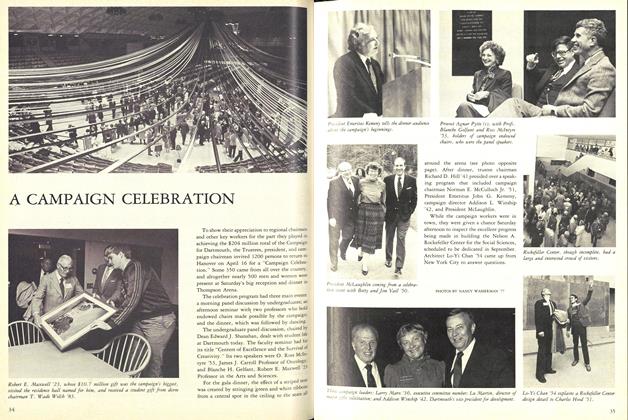

Cover StoryA CAMPAIGN CELEBRATION

May 1983 -

Sports

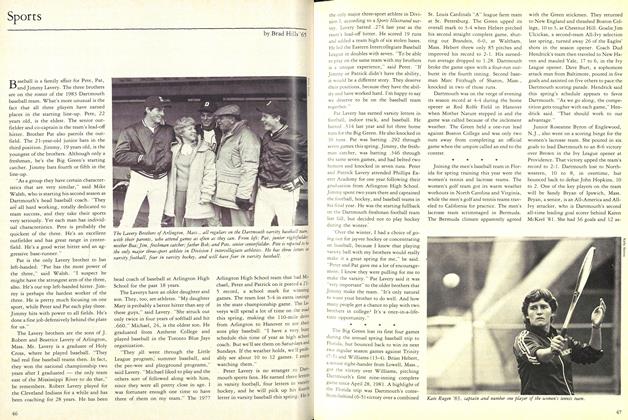

SportsSports

May 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

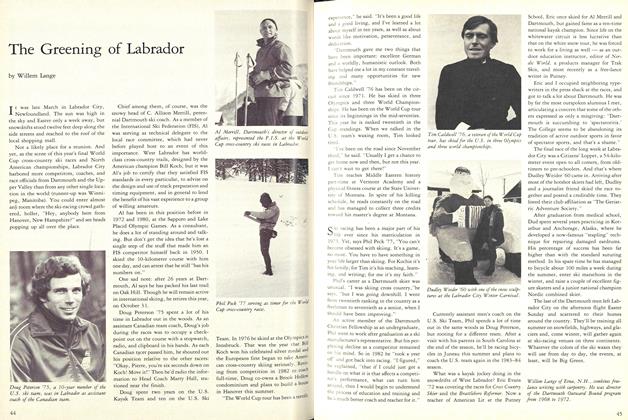

ArticleThe Greening of Labrador

May 1983 By Willem Lange

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

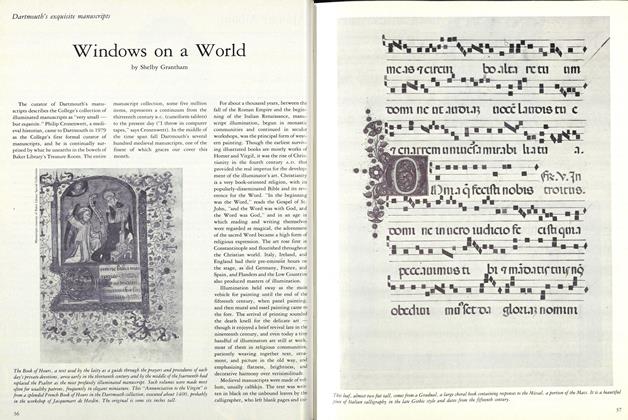

FeatureWindows on a World

DECEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

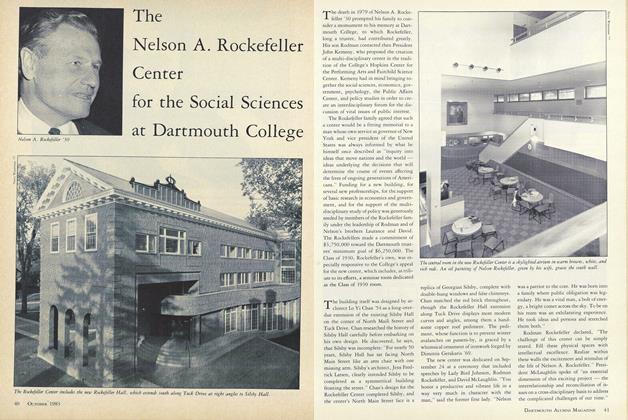

FeatureThe Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences at Dartmouth College

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham

Article

-

Article

ArticleImposters Again

January 1935 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Women's Club of Boston Holds 25th Anniversary Luncheon

June 1955 -

Article

ArticleMr. Mayor

OCTOBER 1989 -

Article

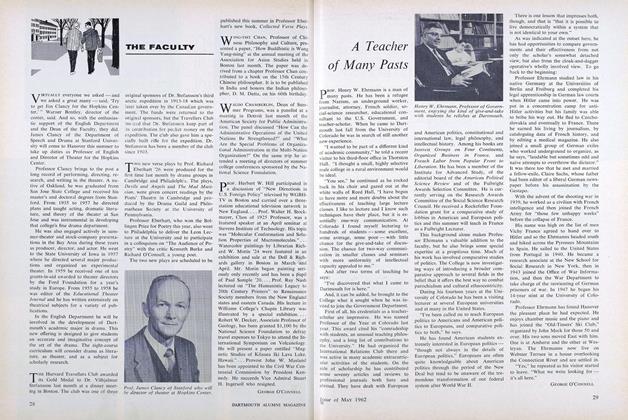

ArticleA Teacher of Many Pasts

May 1962 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

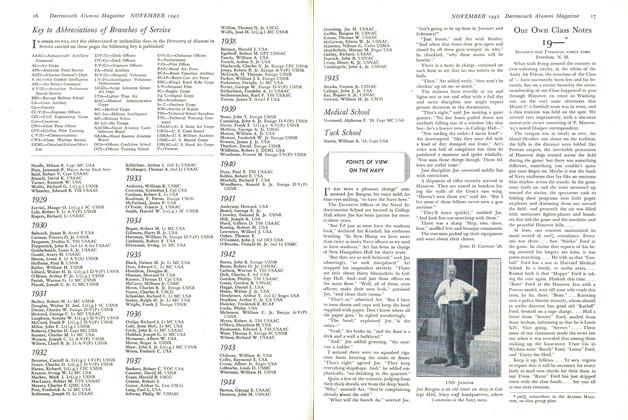

ArticlePOINTS OF VIEW ON THE NAVY

November 1942 By Jonh D. Cannon '26 -

Article

ArticleWatch Your Back

OCTOBER 1997 By Michelle Gregg '99