It is a special privilege and honor for me to be with you members of the graduating class of Dartmouth, family and friends on this most auspicious of all days on the college calendar.

Central bankers, I am told, share one characteristic with the Puritans of old New England the haunting fear that someone someplace may be happy. I realize that this is hardly the time for me to reinforce that reputation; graduation day is a time for congratulation and celebration, here even more than most places given that atmosphere that seems to inspire a special loyalty and cohesion among the sons and daughters of Dartmouth.

But I also suspect that the Dartmouth atmosphere has not been entirely free of some of the characteristics affecting colleges generally in recent years a more serious mood, more conserva- tive and harder working, with a tinge of concern about a tougher economic reality out there in the real world.

I am told Bob Hope, started a commencement address a few years ago by saying his job was to talk about entering the real world. He summed up his advice in one word: "Don't."

But that, of course, is no option even if some of you can defer the day of entry for a year or two in graduate or professional schools. In any event, my name is not Bob Hope.

Quite the contrary, I am convinced that, after too many years of economic turbulence and difficulty, we have the makings of a new era of economic vitality and growth before us. A large part of my conviction is precisely that, out of the last few years, we have learned again some of the basic requirements for a healthy econo- my.

It's hard now to recall the exuberance that so many felt about the economic outlook in the mid- and1 late-19605. Then, we inherited two decades of unparalleled prosperity in the Western World. Against that background, the action took hold that we had finally learned how to maintain reasonably steady growth and low unemployment that we could, as the saying goes, count on it."

But that sense of national self-satisfaction fell prey to a human failing we began, so to speak, to "believe the press notices" instead of working to justify them. Those were the days when economists wrote learned dissertations on how much a college education was worth in dollars and cents while simultaneous- ly college students all over the country decided academic stan- dards weren't so important after all.

Ten years later, when you seniors were freshmen, the vision had turned sour. For a decade, the inflation rate had accelerated, and contrary to the textbooks, levels of unemployment tended 'g er at the same time. We were forcibly reminded cheap energy was a thing of the past, and our natural resources and environment needed protection. Productivity growth had practi- y ceased. The average worker saw the real value of his pay- declining, and speculation in real estate, gold, silver and ot* er s°-called tangibles was rife.

Against that background, a sense developed that something was wrong, and that a base for economic growth and financial stability could not be restored without dealing with inflation. It was a willingness to take and to support strong measures to that end, to restore incentives for investment and growth.

As you well know, that process has not been an easy one. In retrospect, no doubt the job could have been done better with less pain and more quickly. We could have reduced the pressures on interest rates and credit markets by smaller budget deficits; we could have had a more favorable world environment; we could have had labor and management adjust more rapidly to the prospects for greater price stability; conceivably, around the edges, we could even have had a better monetary policy!

But let's not engage in wishful thinking; in the best of circum- stances, we should never have anticipated that dealing with ingrained inflation, and rebuilding a base for growth and pro- ductivity would be fast and easy.

All that I would argue is that we had no real choice but to face up to some basic problems, and today the outlook is much improved. I'm not going to argue that you are entering the economic nirvana, but inflation is down, and we can see signs of improving productivity. Recovery is underway, and I believe we are in the process of building habits and expectations that can be consistent with greater stability and growth for years ahead.

There is a television commercial for an investment house that, in its partly facetious way, captures the mood: "They make money the old fashioned way. They earn it." I doubt that line would have struck so responsive a chord ten years ago.

Obviously, I'm in no position to offer guarantees along with my vision whether or not it is realized is going to depend, in no small part, both on our wisdom as a nation and on our willingness to "earn it."

One obvious threat lies in the prospect of continued high federal budget deficits ranging to a fifth or a quarter of the entire budget if no corrective action is taken. The outline of the problem is familiar enough, and I won't linger over it. The potential for a continuing clash in the market place as growth in the private economy generates more private credit demands a clash that would be reflected in continuing abnormally high interest rates and doubtful prospects for investment and housing is clear enough.

We are reminded almost daily of the strains and pressures in international credit markets as many developing countries strug- gle with tens of billions of debts, debts accumulated partly in the expectation that the burdens would be washed away by inflation. Too many of our industries face severe competitive problems abroad and difficulty in adjusting to changing circumstances at home. And those problems, too, are complicated by an histori- cally high level of interest rates.

In this situation, there is, of course, a tendency to seek out some single, all-embracing kind of answer. In particular, some indulge in the hope or the conviction that monetary policy if only conducted just right alone could somehow make it all ccme out appropriately.

In the end, the creation of more money or less isn't going to solve the budgetary problem; that requires hard action to reduce expenditures or increase revenues in real terms. Interest rates aren't going to move lower, certainly not for long, if lenders and borrowers alike remain skeptical about our ability to deal with inflation. And they rightly look to monetary policy to retain the necessary discipline.

I would suggest, in this area as others, you retain a healthy skepticism about single dramatic answers. Mencken had it about right years ago when he observed "For every complicated prob- lem there is a solution that is simply, easy, and wrong."

Another line of commentary on monetary policy accepts the need for discipline, but insists that discipline be incorporated in a fixed rule. I readily understand and sympathize with the desire to, in a sense, "pin down" monetary policy for the future. And all the proposals have a certain element of historical or analytic validity the idea that markets might be reassured by pre-set monetary growth targets for years ahead, by restricting the price of gold and other commodities, or by keeping foreign exchange rates or interest rates, real or nominal, short or long, within some range. The fact that those proposed rules are mutually inconsis- tent is enough to cast some suspicion on their eternal validity. In economics, as in other areas, there is wisdom in Alfred North Whitehead's remark that "There are no whole truths; all truths are half-truths. It is trying to treat them as whole truths that plays the devil."

I make no apology for the fact that the approach of the Federal Reserve through the years has necessarily been more pragmatic, relying on a certain amount of judgment in the formulation and conduct of policy. That approach seems to me an inescapable consequence of the changing institutional and financial environ- ment in which we operate. But to be at all successful we do have to retain a certain consistency and discipline in our basic ap- proach, keeping in mind that the consequences of action today are likely to persist over a long period of time.

It is in large part for that reason that, at the start of the Federal Reserve System some 70 years ago, the Congress incorporated into its charter a certain independence in its own resources.

Sometimes the objection is made that the whole thing is undemocratic that the policy decisions of the Federal Reserve are not made by elected officials. But it is elected officials who have created and maintained the structure and choose the mem- bers of the Board of Governors. And, of course, in a larger sense we are qot indeed, we should not and could not be —- independent of the "body politic." We are a part of government in a larger sense, and no monetary policy could be sustained for long without broad understanding and support of the people whose lives, in the end, are affected.

What does seem to me to have served us well over the years, and to be as relevant today as when the Federal Reserve was founded,jis that monetary policy be formulated and conducted with a degree of insulation from partisan and passing poilitical pressures, with professionalism, and with emphasis on the long- run national interest.

I have ventured to touch upon this matter this morning for two reasons. First of all, all of you have a special appreciation for another institution of a certain independence that has both in- spired great loyalty and served our nation well. Dartmouth is three times as old as the Federal Reserve and that famous Dartmouth College case more than 150 years ago tested the proposition that independent education institutions could sur- vive and prosper in the search for knowledge, understanding, and the public interest.

Second, I am convinced that with a little foresight and wis- dom, we together can meet the economic problems before us. Part of my confidence is based upon the fact that we have already come a long way toward laying the base for renewed growth part is based upon the simple notion that the challenges that we face are evident, and being known, they can be dealt with.

Graduates, you will soon be dealing with these problems first hand. Maybe in some respects it all sounds exhausting and uncomfortable not exactly in the image of the "laid back" years. But let me assert you will also find the environment challenging and invigorating and that out of the process will come the growth in jobs and satisfaction we all want.

You have been privileged to be part of this special place, and I hope you will retain the values that you have shared in the college experience the spirit of free inquiry, a willingness to work hard to achieve your goals and to have some fun in the process, the sense that you own success and satisfaction are bound up tightly with those of others.

You are under no illusion that life "out there," beyond the rolling hills of New Hampshire, is a bed of roses. It is a world where hard work, and courage, and human concern can be amply rewarded in more ways than you may now imagine. And I also wish you a little luck for sooner than you realize, it will be a world shaped not by my generation but by yours.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe View from the Women's Locker Room

June 1983 By Agnes Kurtz -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

June 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

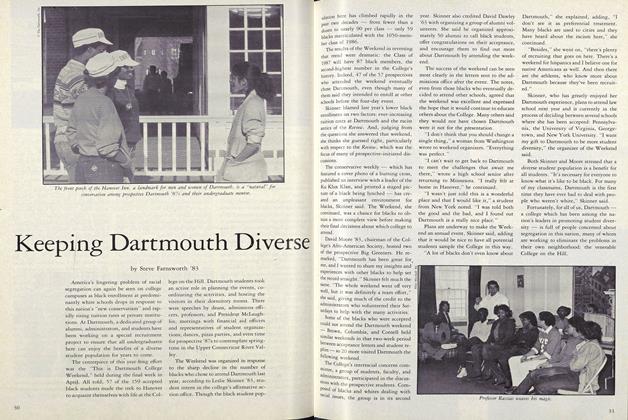

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

June 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Feature

FeatureJustifiable Pesticide

June 1983 By Robert Bell '67 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

June 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Feature

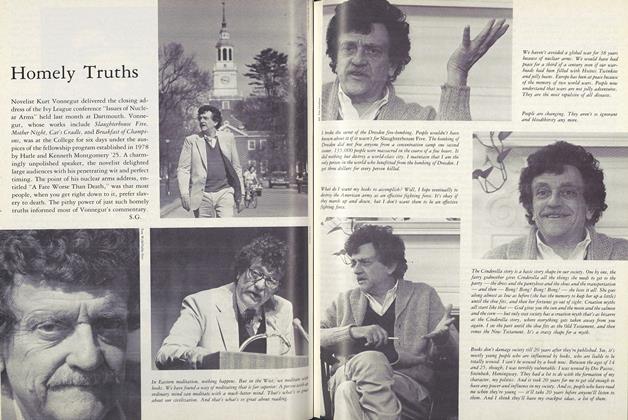

FeatureHomely Truths

June 1983 By S.G.