Some of the Whys and Wherefores Behind The Required Freshman English Course

DEAR DAD: .... You asked me what I signed up here for. Well, I'm taking American History, Eccy 1, French 5, Hygiene, and Geology—l thought that would be the best science for me to take if I am going into the real-estate business. Oh yes, I am taking Freshman English, too. We have to take that, like Hygiene. And now in closing I will only say that if you want to send me 25 bucks more, I could sure use it.

Your loving son Ed

Ed is quite right. He may take German instead of French, Biology instead of Geology; numerous are the subjects from which he may choose. But unless he is one of a small number of men who in a qualifying examination demonstrate their exceptional maturity as readers and skill as writers, Ed along with Joe and Bob and most of the other Dartmouth freshmen will find himself enrolled throughout his first semester in English 1 and throughout his second semester in English 2, three times a week, in someone of the thirty-two or -three sections which represent the most considerable single task of the English department.

Ed's father or mother may naturally ask "Why is Freshman English a 'must'?" The answer is not simple; there are several reasons. Perhaps the "why" can be grasped more clearly if we look first at the 'what'. What goes on in English 1-2?

Briefly, what goes on is reading and writing, speaking and listening. And these four are one. For they are all forms of communication, the fundamental social activity of civilized man. Freshman English aims to increase the student's competence in communication.

At first glance, an onlooker might get the impression that Freshman English at Dartmouth is a somewhat schizoid affair. The books the student is asked to buy and study might seem rather remote from the kind of writing he is asked to do, or indeed, from any kind he could possibly do. At present, the reading in English 1 comprises selections from the Old Testament, read in the familiar King James version; some of Chaucer's' Canterbury Tales, together with his "Prologue" to these, read in the Middle English in which Chaucer wrote; and Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet and Othello. The reading in English 2 comprises an amount of Milton's Paradise Lost equivalent to four or five of its twelve 'books'; any three of the works included in a book called Four Great American Novels which contains Hawthorne's The ScarletLetter, Melville's Billy Budd, Twain's Daisy Miller; portions of The Viking Portable Conrad (of course, the late Joseph is the author mentioned); and selections from Untermeyer's combined anthologies entitled Modern American Poetry and Modern English Poetry, these selections being centered in the work of several of the most important poets of our times.

The writing expected of the freshman is, to put it mildly, quite unlike this reading, not only in quality but in kind. Besides the usual hour and final exams, designed chiefly to test the student's grasp of the books he has studied, there are a number of 500-word themes—some ten to twelve during the first semester, and four during the earlier weeks of the second semester. Some of these themes may be on topics connected in some way with the assigned reading. Some may practise the freshman in various sorts of writing—for example, an explanation of some mechanism or activity; an argument; a portrait of a friend (or, what is sometimes easier, an enemy). Some themes may be left to the student's own choice of a subject or aim. A single topic might be prescribed for all the themes of a given section of freshmen, though few freshmen instructors, each of whom follows his own ideas of pedagogy in giving out theme assignments, restrict the student's choice so narrowly as that. During the latter part of the second semester the writing of shorter themes is replaced by the composition of a single theme of 3500 or more words in length. This is somewhat grandly called a "research theme," by which is meant no more that that the topic must oblige the freshman to consult books and periodicals in the college library in order to collect his material. Before beginning work on this long theme, the freshmen are taken on a fairly detailed tour of the reference room in Baker Library. Other aids to freshman writers are individual conferences with instructors—at least one a term for each student in Freshman English, and as many more as he wishes; and a Writing Clinic maintained by the department for any student handicapped or encountering difficulty in his writing in any course in any year of the college, no matter whether the student is already enrolled in an English course or not.

At this point one might well ask "If freshman writing is largely of such a work- a-day sort, why don't the freshmen study books more closely related in kind to their own writing? If they write themes about personal experiences, why don't they read books of modern biography or travel? If they write arguments, why don't they read articles about current issues? Why must they read a sacred list of books which, however great, are remote from them in time?"

A full answer to these questions would carry us far afield. A few comments must suffice here. First, the department has in times past tried the kinds of reading such questions suggest, and has found them unsatisfactory. For one thing, students of college age should not need to read a book— Camping in Alaska—in order to write a successful theme on "The Grizzly I Almost Met." Literary models for these intimate adventures are prep-school stuff. The average freshman—or so our experience indicates can usually write a brief personal narrative about as well when he enters college as he ever will later. As for current political and economic issues, these are better handled by the several departments of the social sciences specially devoted to them—not to overlook the point that at Dartmouth, a course required of all seniors is considered a more suitable opportunity for exploring the intricate issues of our world today. Nor does the list of books studied by freshmen represent any sacred list. Nearly every year the list is altered in some particular; one book may be dropped or another added by majority vote of the instructors working in the course.

Yet in truth the books are not best thought of as a list at all. Nobody supposes that these books comprise all the great writing, not even all the very greatest of the great writing, in the English language. Some of them the student may have read before. No matter. A great book can be defined as a book that needs to be re-read in order to be read. The reading in Freshman English has been chosen so as to introduce the student to the mind of our Anglo-American civilization at successive stages in its career—and therefore to patterns and influences still to be discerned in the mind of today. That the past lives in the present is in some ways apparent to anybody. Hamlet, Falstaff, Macbeth we know them as we know our contemporaries, and from them we obtain insights into the possibilities of human nature in our time. But the past lives in the present in more pervasive if less obvious ways. When we say, for example, "Stokes is in a bad humor today," we may not realize that in the word "humor" survives the medical science and psychology of Chaucer's day, even if, like an unusual case of measles, it has changed its spots. To learn what a "humor" meant to Chaucer is at the same time to develop a richer apprehension of the rather different uses of that word today. Countless other examples, in matters great and small, could be given of the truth that the life of the past and the life of the present are one life.

The relation of Freshman English to speaking and listening needs less comment. Training in platform speaking and debate is handled by another department of instruction the Department of Speech. It likewise handles all work in the correction of speech defects and in the analysis and improvement matters require the use of intricate laboratory equipment, familiarity with which is a profession in itself. What Freshman English does to encourage speaking is to keep its recitation sections relatively small, containing on the average twenty-one or two men. Hence recitations of the old-fashioned kind ("Mr. A, what was Shakespeare's first name?" "Mr. B, what was the date of his birth?" "Mr. C, where was he born?") need not be used in an attempt to discover whether the class has "studied its lesson." Ideas arising from the reading can be introduced by the instructor, and left to be explored by the spontaneous discussion of the class. As for the students' training in listening, the propensity of professors for talking is too well known to require further comment here.

And what of performance? Freshman English may aim to do this or that, but what does it do? Well, the answer is hard to come by. For English is not a mass of data, such as one may acquire in a course in, say, commercial geography. English is the exploration of an activity—the activity of communication. Therefore the rewards are not facts; the rewards are skill and enjoyment. In writing better about matters within the student's grasp—there comes in the skill. In reading more intelligently about matters just at the edge of the student's reach—there, we hope, comes in the enjoyment. The student of writing and of literature is in fact much like a dweller in some such pleasant region as the Hanover plain. He has, let us say, some ground which he owns, with a house on it where he lives. All around lie hill and valley, field and woodland, which he does not own, but which are good to look at and to explore. And there is an interesting paradox here. By cultivating and adorning his own plot and home, the dweller is of most use to his fellows. So with the student's writing. But by beholding what he does not own, what lies toward the horizon, he is of most use to himself. It is when some inviting prospect at moments takes the eyes with beauty, when some summit glimpsed now and then lifts up the heart with joy—it is then that life, one's own life, to be oneself, seems good. So, we hope, with the student's reading. The aim of English 1-2 is that all Dartmouth freshmen may use some part of English better, and like some part of English more. Never to lose sight of this aim will be our best performance.

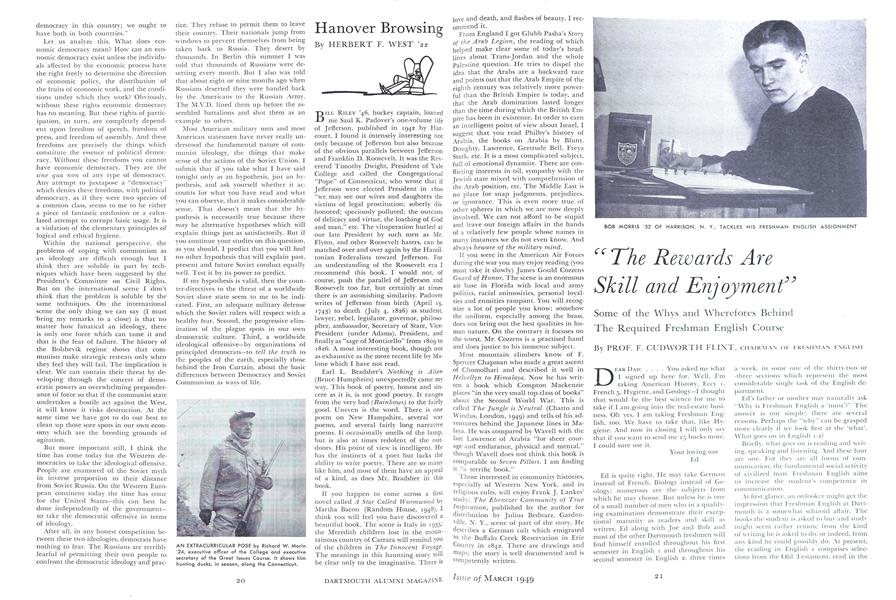

808 MORRIS '52 OF HARRISON, N. Y„ TACKLES HIS FRESHMAN ENGLISH ASSIGNMENT

THE AUTHOR: PROF. F. CUDWORTH FLINT

CHAIRMAN OF FRESHMAN ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleInternational Communism

March 1949 By SIDNEY HOOK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

March 1949 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, EDWARD B. LUITWIELER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

March 1949 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, EDWIN F. STUDWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1949 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART III, LEON H. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

March 1949 By FRANKLYN J. JACKSON, WILLIAM H. SCHERMAN

Article

-

Article

ArticleMoves to Herald

April 1941 -

Article

ArticleChange at the Medical School

November 1978 -

Article

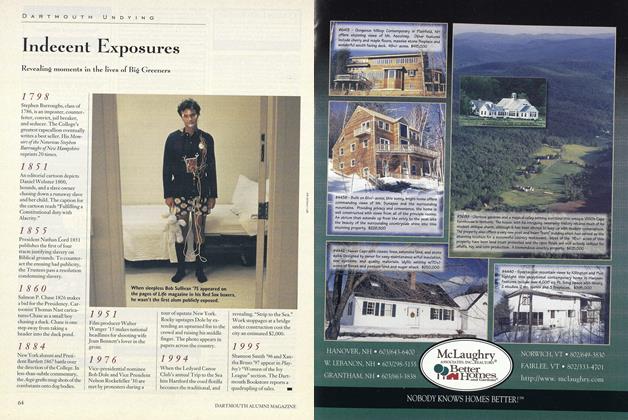

ArticleIndecent Exposures

May 1998 -

Article

ArticleTa-Te-Tung

MARCH 1930 By Charles E. Butler -

Article

ArticleCollege of a Thousand Elms

June 1937 By PROFESSOR CHARLES J. LYON -

Article

ArticleNotes on a Distinguished Defendant and the Supreme Court’s Great non-decision

DEC. 1977 By R. H. R.