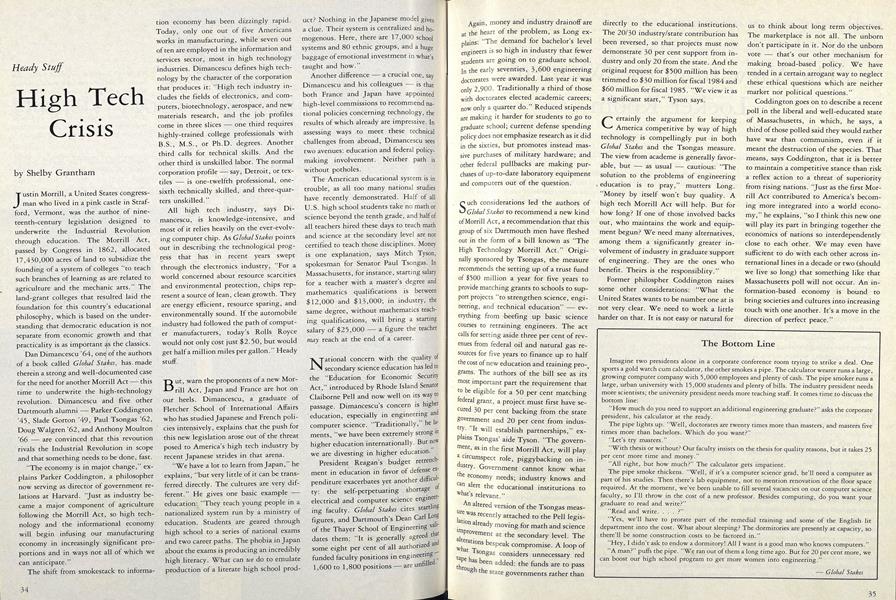

Heady Stuff

Justin Morrill, a United States congressman who lived in a pink castle in Strafford, Vermont, was the author of nineteenth-century legislation designed to underwrite the Industrial Revolution through education. The Morrill Act, passed by Congress in 1862, allocated 17,430,000 acres of land to subsidize the founding of a system of colleges "to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts." The land-grant colleges that resulted laid the foundation for this country's educational philosophy, which is based on the understanding that democratic education is not separate from economic growth and that practicality is as important as the classics.

Dan Dimancescu '64, one of the authors of a book called Global Stakes, has. made therein a strong and well-documented case for the need for another Morrill Act - this time to underwrite the high-technology revolution. Dimancescu and five other Dartmouth alumni Parker Coddington '45, Slade Gorton '49, Paul Tsongas '62, Doug Walgren '62, and Anthony Moulton '(56 are convinced that this revoution rivals the Industrial Revolution in scope and that something needs to be done, fast.

"The economy is in major change," explains Parker Coddington, a philosopher now serving as director of government relations at Harvard. "Just as industry became a major component of agriculture following the Morrill Act, so high technology and the informational economy will begin infusing our manufacturing economy in increasingly significant proportions and in ways not all of which we can anticipate."

The shift from smokestack to informa- tion economy has been dizzingly rapid. Today, only one out of five Americans works in manufacturing, while seven out often are employed in the information and services sector, most in high technology industries. Dimancescu defines high technology by the character of the corporation that produces it: "High tech industry includes the fields of electronics, and computers, biotechnology, aerospace, and new materials research, and the job profiles come in three slices one third requires highly-trained college professionals with 8.5., M.S., or Ph.D. degrees. Another third calls for technical skills. And the other third is unskilled labor. The normal corporation profile - say, Detroit, or textiles _ is one-twelfth professional, onesixth technically skilled, and three-quarters unskilled."

All high tech industry, says Dimancescu, is knowledge-intensive, and most of it relies heavily on the ever-evolving computer chip. As Global Stakes points out in describing the technological progress that has in recent years swept

through the electronics industry, "For a world concerned about resource scarcities and environmental protection, chips represent a source of lean, clean growth. They are energy efficient, resource sparing, and environmentally sound. If the automobile industry had followed the path of computer manufacturers, today's Rolls Royce would not only cost just $2.50, but would get half a million miles per gallon." Heady stuff.

But, warn the proponents of a new Morrill Act, Japan and France are hot on our heels. Dimancescu, a graduate of Fletcher School of International Affairs who has studied Japanese and French policies intensively, explains that the push for this new legislation arose out of the threat posed to America's high tech industry by recent Japanese strides in that arena.

"We have a lot to learn from Japan," he explains, "but very little of it can be transferred directly. The cultures are very different. " He gives one basic example education: "They teach young people in a nationalized system run by a ministry of education. Students are geared through high school to a series of national exams and two career paths. The phobia in Japan about the exams is producing an incredibly high literacy. What can we do to emulate production of a literate high school prod- uct? Nothing in the Japanese model gives a clue. Their system is centralized and homogenous. Here, there are 17,000 school systems and 80 ethnic groups, and a huge baggage of emotional investment in what's taught and how."

Another difference a crucial one, say Dimancescu and his colleagues is that both France and Japan have appointed high-level commissions to recommend national policies concerning technology, the results of which already are impressive. In assessing ways to meet these technical challenges from abroad, Dimancescu sees two avenues: education and federal policymaking involvement. Neither path is without potholes.

The American educational system is in trouble, as all too many national studies have recently demonstrated. Half of all U.S. high school students take no math or science beyond the tenth grade, and half of all teachers hired these days to teach math and science at the secondary level are not certified to teach those disciplines. Money is one explanation, says Mitch Tyson, spokesman for Senator Paul Tsongas. In Massachusetts, for instance, starting salary for a teacher with a master s degree and mathematics qualifications is between $12,000 and $13,000; in industry, the same degree, without mathematics teaching qualifications, will bring a starting salary of $25,000 a figure the teacher may reach at the end of a career.

National concern with the quality of secondary science education has led to the "Education for Economic Security Act," introduced by Rhode Island Senator Claiborne Pell and now well on its way to passage. Dimancescu's concern is higher education, especially in engineering and computer science. "Traditionally, he laments, "we have been extremely strong in higher education internationally. But now we are divesting in higher education.

President Reagan's budget retrenchment in education in favor of defense ex penditure exacerbates yet another difficulty: the self-perpetuating shortage of electrical and computer science engineer ing faculty. Global Stakes cites startling figures, and Dartmouth's Dean Carl Long of the Thayer School of Engineering validates them: "It is generally agreed that some eight per cent of all authorized funded faculty positions in engineering 1,600 to 1,800 positions are unfile.

Again, money and industry drainoff are at the heart of the problem, as Long explains: "The demand for bachelor's level engineers is so high in industry that fewer students are going on to graduate school. In the early seventies, 3,600 engineering doctorates were awarded. Last year it was only 2,900. Traditionally a third of those with doctorates elected academic careers; now only a quarter do." Reduced stipends are making it harder for students to go to graduate school; current defense spending policy does not emphasize research as it did in the sixties, but promotes instead massive purchases of military hardware; and other federal pullbacks are making purchases of up-to-date laboratory equipment and computers out of the question.

Such considerations led the authors of Global Stakes to recommend a new kind of Morrill Act, a recommendation that this group of six Dartmouth men have fleshed out in the form of a bill known as "The High Technology Morrill Act." Originally sponsored by Tsongas, the measure recommends the setting up of a trust fund of $500 million a year for five years to provide matching grants to schools to support projects "to strengthen science, engineering, and technical education" everything from beefing up basic science courses to retraining engineers. The act calls for setting aside three per cent of revenues from federal oil and natural gas resources for five years to finance up to half the cost of new education and training programs. The authors of the bill see as its most important part the requirement that to be eligible for a 50 per cent matching federal grant, a project must first have secured 30 per cent backing from the state government and 20 per cent from industry- It will establish partnerships," explains Tsongas' aide Tyson. "The government, as in the first Morrill Act, will play a circumspect role, piggybacking on in- dustry. Government cannot know what the economy needs; industry knows and can alert educational institutions to what's relevant."

An altered version of the Tsongas measure was recently attached to the Pell legislation already moving for math and science improvement at the secondary level. The alterations bespeak comp[romise. A loop of what Tsongas considers unnecessary red tape has been added: tje finds are to pass through the state governments rather than directly to the educational institutions. The 20/30 industry/state contribution has been reversed, so that projects must now demonstrate 30 per cent support from industry and only 20 from the state. And the original request for $500 million has been trimmed to $30 million for fiscal 1984 and $60 million for fiscal 1985. "We view it as a significant start," Tyson says.

Certainly the argument for keeping America competitive by way of high technology is compellingly put in both Global Stakes and the Tsongas measure. The view from academe is generally favorable, but as usual cautious: "The solution to the problems of engineering education is to pray," mutters Long. "Money by itself won't buy quality. A high tech Morrill Act will help. But for how long? If one of those involved backs out, who maintains the work and equipment begun? We need many alternatives, among them a significantly greater involvement of industry in graduate support of engineering. They are the ones who benefit. Theirs is the responsiblity."

Former philospher Coddington raises some other considerations: "What the United States wants to be number one at is not very clear. We need to work a little harder on that. It is not easy or natural for us to think about long term objectives. The marketplace is not all. The unborn don't participate in it. Nor do the unborn vote that's our other mechanism for making broad-based policy. We have tended in a certain arrogant way to neglect these ethical questions which are neither market nor political questions."

Coddington goes on to describe a recent poll in the liberal and well-educated state of Massachusetts, in which, he says, a third of those polled said they would rather have war than communism, even if it meant the destruction of the species. That means, says Coddington, that it is better to maintain a competitive stance than risk a reflex action to a threat of superiority from rising nations. "Just as the first Morrill Act contributed to America's becoming more integrated into a world economy, " he explains, "so I think this new one will play its part in bringing together the economics of nations so interdependently close to each other. We may even have sufficient to do with each other across international lines in a decade or two (should we live so long) that something like that Massachusetts poll will not occur. An information-based economy is bound to bring societies and cultures into increasing touch with one another. It's a move in the direction of perfect peace."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe View from the Women's Locker Room

June 1983 By Agnes Kurtz -

Feature

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

June 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Feature

FeatureJustifiable Pesticide

June 1983 By Robert Bell '67 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

June 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Feature

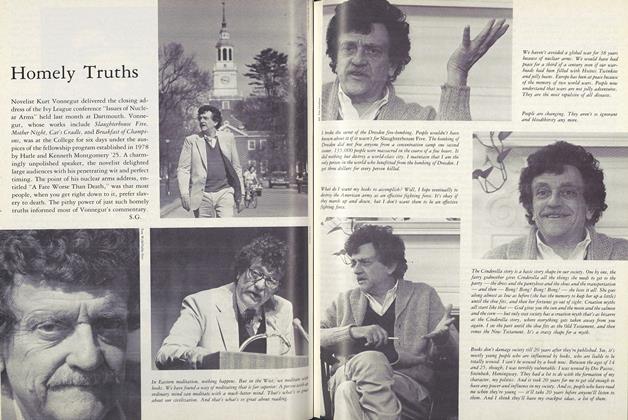

FeatureHomely Truths

June 1983 By S.G. -

Feature

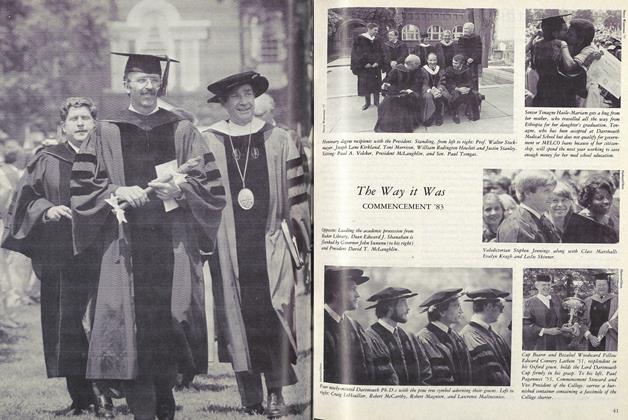

FeatureThe Way it Was

June 1983 By COMMENCEMENT '83

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

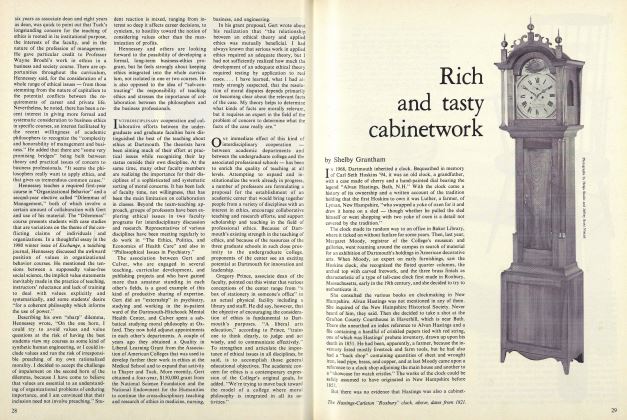

FeatureRich and tasty cabinetwork

March 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

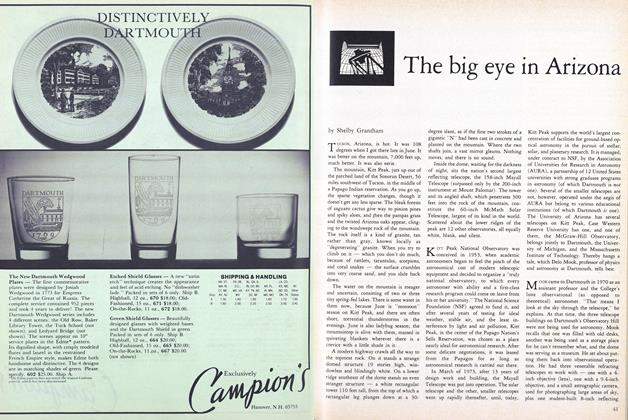

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

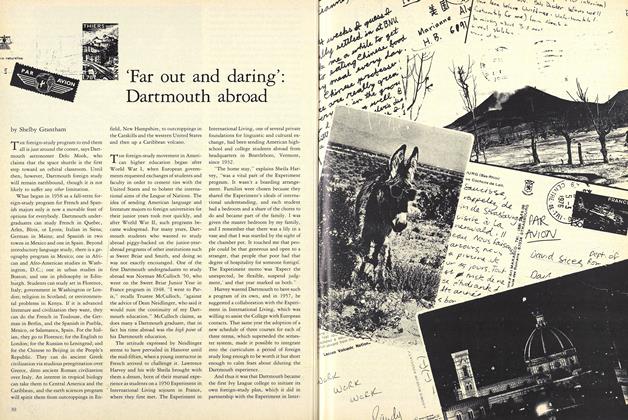

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

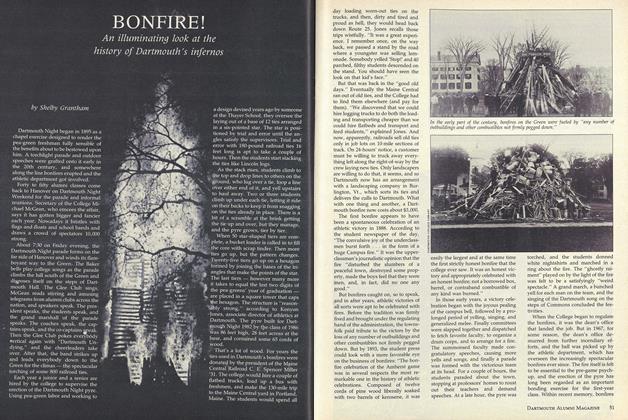

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

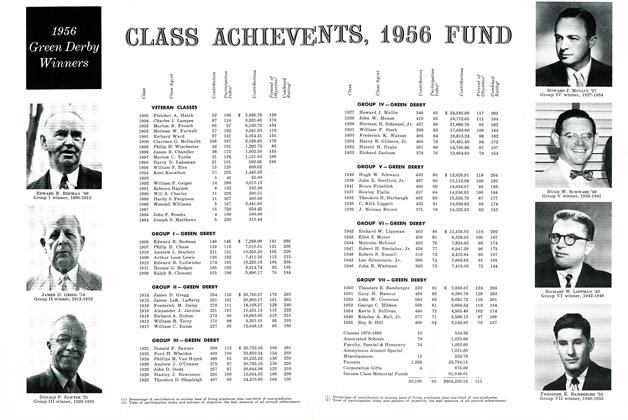

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVENTS, 1956 FUND

December 1956 -

Feature

FeatureMammalogist

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

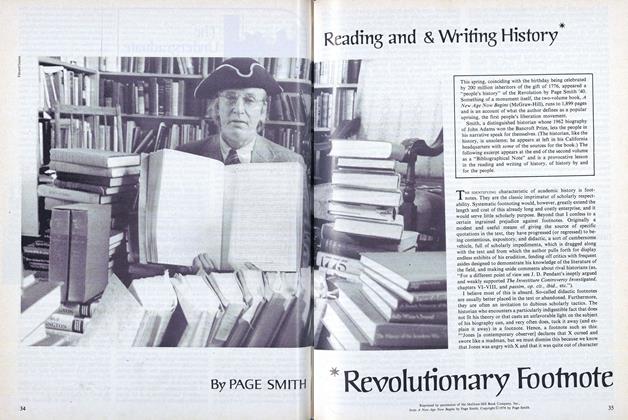

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureNaming the Animals

OCTOBER 1996 By Robert Pack '51 -

Cover Story

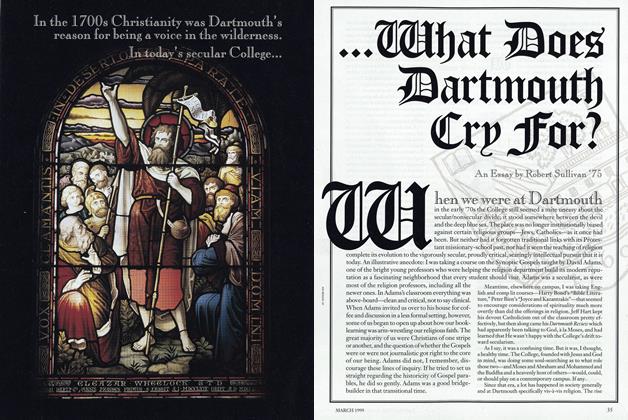

Cover StoryWhat Does Dartmouth Cry For?

MARCH 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2012 By SPORTING NEWS VIA GETTY IMAGES