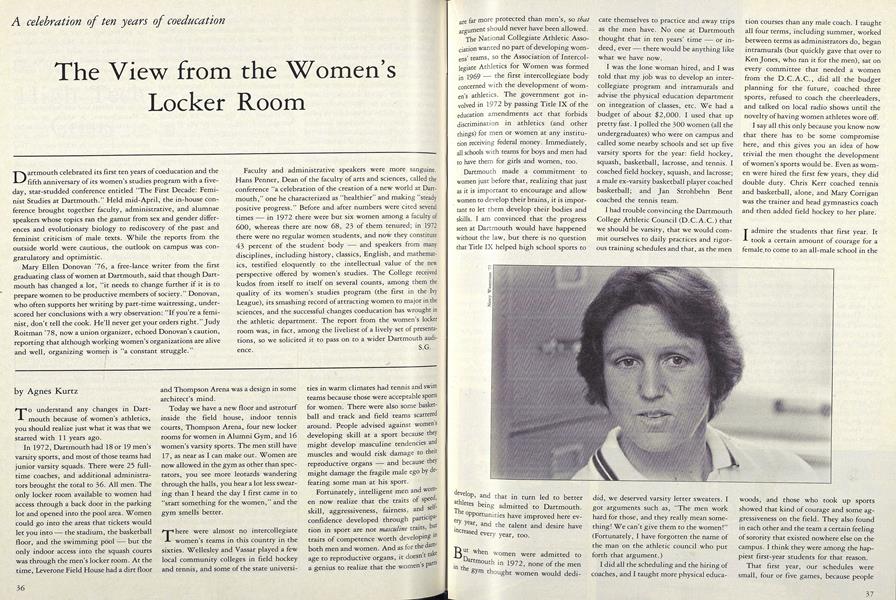

A celebration of ten years of coeducation

Dartmouth celebrated its first ten years of coeducation and the fifth anniversary of its women's studies program with a fiveday, star-studded conference entitled "The First Decade: Feminist Studies at Dartmouth." Held mid-April, the in-house conference brought together faculty, administrative, and alumnae speakers whose topics ran the gamut from sex and gender differences and evolutionary biology to rediscovery of the past and feminist criticism of male texts. While the reports from the outside world were cautious, the outlook on campus was congratulatory and optimistic.

Mary Ellen Donovan 76, a free-lance writer from the first graduating class of women at Dartmouth, said that though Dartmouth has changed a lot, "it needs to change further if it is to prepare women to be productive members of society." Donovan, who often supports her writing by part-time waitressing, underscored her conclusions with a wry observation: "If you're a feminist, don't tell the cook. He'll never get your orders right." Judy Roitman '78, now a union organizer, echoed Donovan's caution, reporting that although working women's organizations are alive and well, organizing women is "a constant struggle."

Faculty and administrative speakers were more sanguine. Hans Penner, Dean of the faculty of arts and sciences, called the conference "a celebration of the creation of a new world at Dartmouth, "one he characterized as "healthier" and making "steady positive progress." Before and after numbers were cited several times —in 1972 there were but six women among a faculty of 600, whereas there are now 68, 23 of them tenured; in 1972 there were no regular women students, and now they constitute 43 percent of the student body and speakers from many disciplines, including history, classics, English, and mathematics, testified eloquently to the intellectual value of the new perspective offered by women's studies. The College received kudos from itself to itself on several counts, among them the quality of its women's studies program (the first in the Ivy League), its smashing record of attracting women to major in the sciences, and the successful changes coeducation has wrought in the athletic department. The report from the women's locker room was, in fact, among the liveliest of a lively set of presentations, so we solicited it to pass on to a wider Dartmouth audience.

To understand any changes in Dartmouth because of women's athletics, you should realize just what it was that we started with 11 years ago.

In 1972, Dartmouth had 18 or 19 men's varsity sports, and most of those teams had junior varsity squads. There were 25 fulltime coaches, and additional administrators brought the total to 36. All men. The only locker room available to women had access through a back door in the parking lot and opened into the pool area. Women could go into the areas that tickets would let you into the stadium, the basketball floor, and the swimming pool but the only indoor access into the squash courts was through the men's locker room. At the time, Leverone Field House had a dirt floor and Thompson Arena was a design in some architect's mind.

Today we have a new floor and astroturf inside the field house, indoor tennis courts, Thompson Arena, four new locker rooms for women in Alumni Gym, and 16 women's varsity sports. The men still have 17, as near as I can make out. Women are now allowed in the gym as other than spectators, you see more leotards wandering through the halls, you hear a lot less swearing than I heard the day I first came in to "start something for the women," and the gym smells better.

There were almost no intercollegiate women's teams in this country in the sixties. Wellesley and Vassar played a few local community colleges in field hockey and tennis, and some of the state universi- ties in warm climates had tennis and swim teams because those were acceptable sports for women. There were also some basketball and track and field teams scattered around. People advised against womens developing skill at a sport because they might develop masculine tendencies and muscles and would risk damage to their reproductive organs and because they might damage the fragile male ego by defeating some man at his sport.

Fortunately, intelligent men and worn en now realize that the traits of speed, skill, aggressiveness, fairness, and self. confidence developed through participation in sport are not masculine traits, but traits of competence worth developing in both men and women. And as for the damage to reproductive organs, it doesn't a genius to realize that the women's Part are far more protected than men's, so that argument should never have been allowed.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association wanted no part of developing womens' teams, so the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women was formed in 1969 the first intercollegiate body concerned with the development of women's athletics. The government got involved in 1972 by passing Title IX of the education amendments act that forbids discrimination in athletics (and other things) for men or women at any institution receiving federal money. Immediately, all schools with teams for boys and men had to have them for girls and women, too.

Dartmouth made a commitment to women just before that, realizing that just as it is important to encourage and allow women to develop their brains, it is important to let them develop their bodies and skills. I am convinced that the progress seen at Dartmouth would have happened without the law, but there is no question that Title IX helped high school sports to cyclop, and that in turn led to better athletes being admitted to Dartmouth. The oPportunities have improved here every Year, and the talent and desire have Creased every year, too.

But when women were admitted to Dartmouth in 1972, none of the men in the gym thought women would dedi- cate themselves to practice and away trips as the men have. No one at Dartmouth thought that in ten years' time or indeed, ever there would be anything like what we have now.

I was the lone woman hired, and I was told that my job was to develop an intercollegiate program and intramurals and advise the physical education department on integration of classes, etc. We had a budget of about $2,000. I used that up pretty fast. I polled the 300 women (all the undergraduates) who were on campus and called some nearby schools and set up five varsity sports for the year: field hockey, squash, basketball, lacrosse, and tennis. I coached field hockey, squash, and lacrosse; a male ex-varsity basketball player coached basketball; and Jan Strohbehn Bent coached the tennis team.

I had trouble convincing the Dartmouth College Athletic Council (D.C.A.C.) that we should be varsity, that we would commit ourselves to daily practices and rigorous training schedules and that, as the men did, we deserved varsity letter sweaters. I got arguments such as, "The men work hard for those, and they really mean something! We can't give them to the women!" (Fortunately, I have forgotten the name of the man on the athletic council who put forth that argument.)

I did all the scheduling and the hiring of coaches, and I taught more physical educa- tion courses than any male coach. I taught all four terms, including summer, worked between terms as administrators do, began intramurals (but quickly gave that over to Ken Jones, who ran it for the men), sat on every committee that needed a women from the D.C.A.C., did all the budget planning for the future, coached three sports, refused to coach the cheerleaders, and talked on local radio shows until the novelty of having women athletes wore off.

I say all this only because you know now that there has to be some compromise here, and this gives you an idea of how trivial the men thought the development of women s sports would be. Even as women were hired the first few years, they did double duty. Chris Kerr coached tennis and basketball, alone, and Mary Corrigan was the trainer and head gymnastics coach and then added field hockey to her plate.

I admire the students that first year. It took a certain amount of courage for a female to come to an all-male school in the woods, and those who took up sports showed that kind of courage and some aggressiveness on the field. They also found in each other and the team a certain feeling of sorority that existed nowhere else on the campus. I think they were among the happiest first-year students for that reason.

That first year, our schedules were small, four or five games, because people were adding us at the last minute. We had 21 people come out for field hockey (compared to about 50, five years later). Our record was two and two against Colby Sawyer, New England College, Keene, and Smith. Smith wanted to change their game from Thursday to Friday because their coach had found out that half the team wanted to stay at Dartmouth for the weekend; since we only had one spectator to worry about, we changed the game. We had 14 for lacrosse, 9 of them beginners who actually played in the first game they ever saw. One student, Barbara Sands, had played squash, and she was runner-up in the national intercollegiate tournament two years out of four. (I've never had anyone go that far since.) Very few students then had ever run a mile. (Now we are hard pressed to find someone who hasn't.)

We had no trainers or training room because our team room and training room hadn't been finished, and no one could imagine women in the men's training room. The reason, of course, was that the men weren't used to having to put clothes on to walk from their locker room to their training room.

That first year, we spent money on equipment, saving uniforms for the second year, when we knew we had the commitment. The members of the teams bought their own T-shirts and shorts for uniforms. We ran five sports on $2,500. No one traveled by bus; very few teams even ate, let alone at McDonald's; and the sole weekend trip had four people to a room.

The second year we had eight or 'nine games on each schedule, uniforms, and another full-time coach, and we had proven that we were worthy of weekend trips. That was 1973-74, the year of the energy crisis, when gas stations closed on Sundays.

In February of that year I took the squash team to New Haven for the nation- al team championships. We should have had enough gas to get home by filling the van on Saturday, but New Haven was famous for its watered-down gas. About 25 miles south of here, on Route 91, a mile from Exit 9 and a closed gas station, and in the dark, we ran out of gas. My first thought was that if we didn't make it, everyone would blame it on women in general: they can't handle these crises or plan ahead. I realized we had just passed the exit sign, and we were almost at the top of a hill, so we all pushed the van to the top and got in and coasted at least a half mile. I got out, figuring, "We're not too far, I'll call the Campus Police. Maybe they'll come get us." They told me to go back to the van. There was a state police car waiting there and the officer called the local gas attendant and had him open up. We got gas, paid an extra $5.00 service charge, and were home within 20 minutes of our scheduled time. Phew!

Meanwhile, the men's gymnastics team ran out of gas in New York and spent the night in a motel until the stations opened on Monday. The men's squash team ran out of gas on Route 89, hitchhiked home, and had to go back to get the van on Monday.

So much for being macho

So we came. We developed teams, and suddenly we needed more money, coaches, trainers, training rooms, facilities and at least equal sharing of those facilities we could use, office space, and publicity. It's been 11 years. We have 16 varsity teams, club teams, nine full-time women coaches, and five full-time women admin- istrators, equal money for food and travel, an equal number of contests per sport, four new locker rooms, new fields at Chase and Sachem, and Thompson Arena. No wom- an is head coach of two sports: most men and women in the D.C.A.C. coach one sport as head and assist in another.

All this has led to changes in men's athletics, and at Dartmouth in general. Integration of the training room was easily accomplished in our third year. Mary Corrigan was then the women's trainer, and she was needed during football preseason. That meant the men had to wear shorts while Mary taped their pulled groin muscles, and they found out it really wasn't so bad to have women around after all.

With respect to facilities, we have new locker rooms and new fields, but we have learned to share basketball, swimming, squash and indoor practice areas during rainy weather. (Ice hockey is still a struggle.) This sharing has meant that coaches see practice times from 2:00 p.m. to 10:00 or 11:00 p.m. rather than just 3:00 to 5:00 p.m., and they share time and facility by weeks or days whatever suits them and the students' schedules.

It took a while to convince some people that women should have practice uniforms and sweats as the men do and that the most efficient way was to channel everything out of one place. The men got clothes from the basement of Davis Varsity House where no women were allowed. Again, as with the training room, the men would have to learn to pick up their gear before they began to change clothes. In trying to arrange these changes, I got, "Oh, sure. What are the women going to do with jock straps. Do we have to buy bras? Ha, ha?"

It took about a year and a half. Generally, that's what most of the changes took. You have to realize that D.C.A.C. policy was to make haste slowly."

Teaching policy has changed, too. For therr or four years, the women taught every term, whereas only men assistant coaches taught that much. Now all assistant Nt COaches teach, and head coaches teach in the off-season and that is across the board for men and women, except for foot- ball and men's and women's basketball.

Integrating the Sports Information Office has been hard. I have seen two sports information directors leave. The first one refused to say "men's varsity tennis" — it was always "varsity tennis" and "women's tennis." After he left, we were able to get equality in name. We still have a hard time getting publicity, although women's basketball does all right.

Attitudes have changed. The fact that we are here and have proven our commitment through similar practice schedules and equal game schedules has helped to change some of the men's attitudes and has silenced a few who haven't changed.

In the process of growth and development, men's wrestling was dropped in an effort to save money, and both men's and women's gymnastics were dropped a year ago for the same reason.

We have successfully combined the departments of track and field for men and women and crew for men and women. One head coach and two assistants pool their talents to help athletes of both sexes. The men's diving coach also acts as the women's diving coach.

In 1976 Dartmouth had its first Olympic rower —Judy Geer '75.

Dartmouth has won four Ivy basketball titles in a row. That has never happened before. The fact that it was the women's team has been obscured.

The men eat at McDonald's more often, the women drink more beer.

Many of the men administrators and coaches have changed since we came, but it

is interesting to note that to date every woman coach hired full-time has remained. That fact alone has contributed significantly to the quality of the teams, because continuity is important.

And I close with change number 13: the administrative structure of the D.C.A.C. An increase from 18 teams to 33, with subvarsity teams and clubs growing accordingly, has forced a different set-up in that administration. There are now women in the administrative set-up, and if Seaver Peters is indeed replaced as director of athletics with a woman, we will know we've made a difference.

Aggie Kurtz, legendary founder of women'sathletics at Dartmouth, is currently serving ashead coach of women's squash and assistantcoach of lacrosse.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

June 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

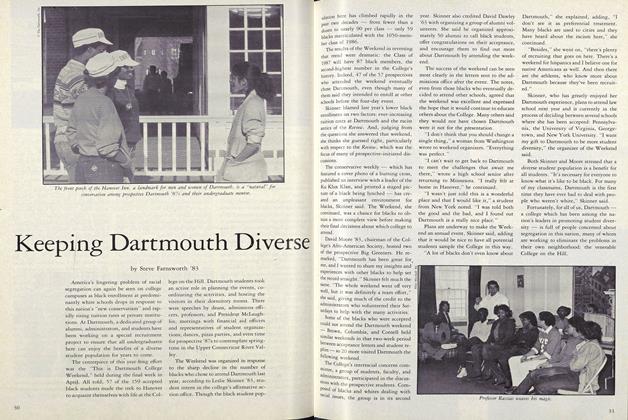

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

June 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Feature

FeatureJustifiable Pesticide

June 1983 By Robert Bell '67 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

June 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Feature

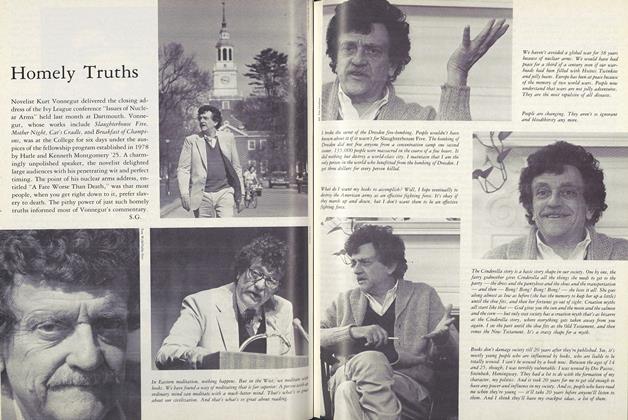

FeatureHomely Truths

June 1983 By S.G. -

Feature

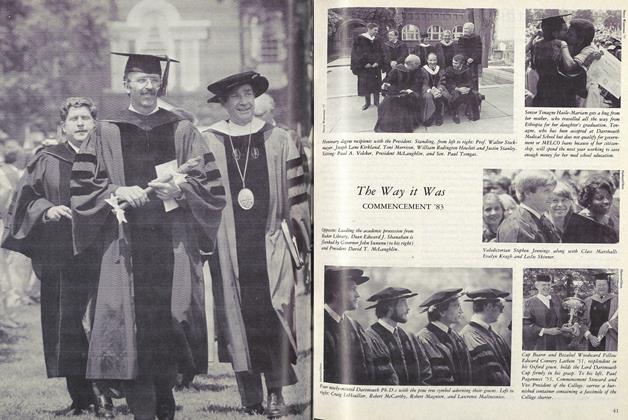

FeatureThe Way it Was

June 1983 By COMMENCEMENT '83

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Ivy League schedule for 1972 ... and some showdown games

OCTOBER 1972 -

Feature

FeatureBoston Bookmaker

May 1974 -

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

MARCH 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

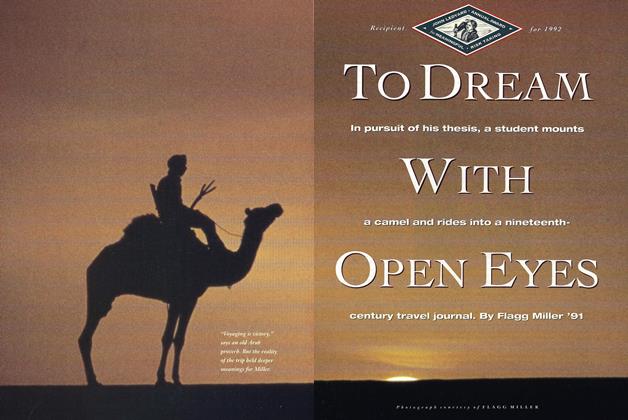

FeatureTo Dream With Open Eyes

APRIL 1992 By flagg Miller '91 -

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureA Dull Little Bug Imperils the College Grant

June 1981 By Ted Winterer