EXECUTIVE COMPUTING: HOW TO GET IT DONE ON YOUR OWN by John M. Nevison '66 Addison-Wesley, 1982, 319 pp., $11.95, paper

During the 1970s Dartmouth had an outstanding computing system. Jack Nevison is remembered as one of the people who showed others how to use it. The studies that he carried out with Arthur Luehrmann remain widely cited as the definitive analysis of computer usage in a university with free access computing.

When he left Dartmouth, Nevison set UP his own company which specializes in Caching computing to executives. Executive Computing is the second of his books. Is is not easy. Despite the glossy advertisements, effective computing reJlres by the user. Moreover the first stages are among the most difficult. It is hard to find ways to give executives the skills that they need to do useful work without going through a long, boring training program.

This book is definitely not an appreciation course for the executive who wishes to have a quick over-view of data processing. It is for somebody with a personal computer who is prepared to take the time to learn how to use it properly. In the true. Dartmouth tradition, the book emphasizes programming as the fundamental computing skill. Since Basic is the most common language on personal computers, all the examples are programmed in Basic. Many books teach programming in Basic, but this one has some special features.

The first is an emphasis on programming with style. Few executives want to write elaborate programs which use all the obscure features of a language. They want to write clear programs which work reliably and are easy to modify. In his other book, The Little Book of BASIC Style: Howto Write a Program You Can Read, Nevison showed that stylish programming is possible in even the most primitive dialects of Basic. The examples in this book are proof of his ideas.

The second special feature is the choice of examples. Within the 319 pages of this book lies a miniature course in the methods of management science and operations research. Net present value, inventory control, network scheduling, linear programming, regression these and many other techniques are introduced, each with its own computer program and a simple example. The examples are artificial, and the description of the techniques is inevitably no more than an introduction; however this does not destroy the value of the text. Most executives will know some of the methods and will find the translation into Basic easy to follow. The other methods will have to be taken mainly on faith, but the'book will still be an interesting introduction, giving a glimmering of many areas.

Executive Computing ends with four ap pendices,an introduction to program structure, utility programs, current equip ment, and a brief introduction to VisiCalc. Some people are coming to think that the way to teach computing to executives is to begin with practical applications, such as VisiCalc, which teach algorithmic thin ing, and leave programming until later. Perhaps the second edition will follow this approach. Until then Executive Computing can be recommended as an ambitious but rewarding text for the executive who really wants to grasp the power of a personal computer.

Professor Arms is director of computing servicesat the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe View from the Women's Locker Room

June 1983 By Agnes Kurtz -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

June 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

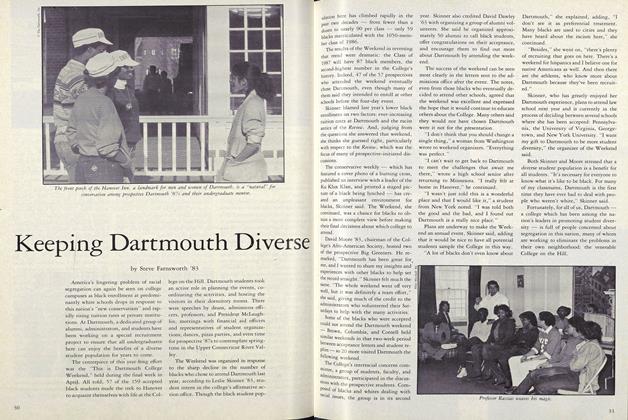

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

June 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Feature

FeatureJustifiable Pesticide

June 1983 By Robert Bell '67 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

June 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Feature

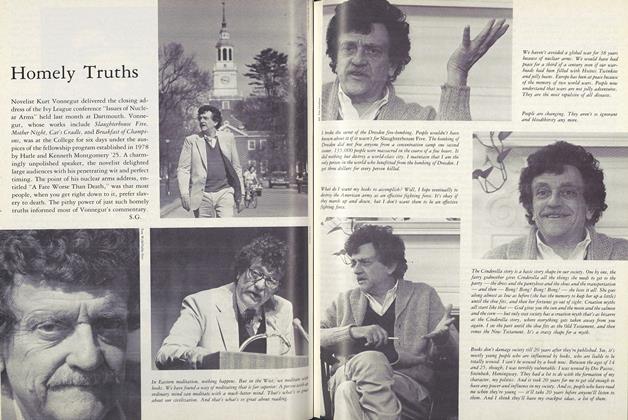

FeatureHomely Truths

June 1983 By S.G.

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

January 1936 -

Books

BooksTHE LAUGH MAKERS: A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF AMERICAN COMEDIANS.

March 1958 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

Books60 CENTURIES OF SKIING

February 1936 By Herbert F. West -

Books

BooksFAREWELL TO FOGGY BOTTOM.

DECEMBER 1964 By HON. ROBERT CHARLES HILL '42 -

Books

BooksTHE LONELY CRO WD: A STUDY OF THE CHANGING AMERICAN CHARACTER

April 1951 By KENNETH A. ROBINSON -

Books

BooksNotes on a Pulitzer not given and on Dr. Bob, a gruff, humane Yankee who helped found AA

JUNE 1977 By R.H.R.