Notes on a Pulitzer not given and on Dr. Bob, a gruff, humane Yankee who helped found AA

JUNE 1977 R.H.R.Notes on a Pulitzer not given and on Dr. Bob, a gruff, humane Yankee who helped found AA R.H.R. JUNE 1977

ONE DOESN'T normally choose to try conclusions with such august bodies as the Pulitzer Prize Advisory Board. For one thing, they sit, presumably, at the hub of the nation's book publishing activities, and we sit in Hanover, New Hampshire. And for another, it smacks of sour grapes. But just this once we've got to disagree with them, august body or not. We hereby file our demurrer. Dear Pulitzer Prize Advisory Board: You were wrong. Yours respectfully, Dartmouth Alumni Magazine.

We confess to the possibility of just the slightest touch of partisanship in our disagreement, perhaps even a faint proprietary feeling, for the case in point is A River Runs Through It by Norman Maclean '24. In our June 1976 issue, very shortly after the book was published, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, with Maclean's and the publisher's permission, reprinted sizable excerpts from A River Runs Through It because we believed it was, quite simply, the finest piece of writing in its genre that we had seen for some years. It was a remarkable literary achievement, we thought, a piece of nature writing that suffered no whit by comparison to the best of the Hemingway fishing stories.

Of course, it was also gratifying to see that others agreed. "A stunning debut," Publisher'sWeekly wrote, and Fly Fisherman called it "one of those rare memoirs that can be called a masterpiece." Book reviewers in major newspapers and national journals added their praise; critical acclaim swelled by the week. Inevitably, by mid-summer a Pulitzer Prize became a real possibility, and later, indeed a near-certainty when the initial selection committee chose A River Runs Through It for the 1976 Pulitzer Prize fiction award.

It was not to be. As Israel Shenker wrote in a rueful piece on Maclean in the New York Times on April 24, "To be 74 years old, to have written a first book that is critically acclaimed and chosen by the Pulitzer Prize fiction jury as this year's best, and then to have the Pulitzer Prize advisory board turn down the choice - such is Norman Maclean's joust with fate." The Times headline writer summed it up more succinctly: "Pulitzer Loser Proves Winner In Other Areas." Amen!

For as Shenker also reports, all is not lost. Not by a long shot. The first printing was 15,000 copies; another is in the works; and two movie producers are currently negotiating for rights to use two of Maclean's stories for films.

So there, august Pulitzer Prize Advisory Board! And good luck to you, Norman Maclean '24. You can put your flyrod over your shoulder and laugh all the way to the river. We hope you turn out to be as good a movie actor as you are a short story writer.

AS NOTED elsewhere in this month's reviews section, a new book on alcoholism by Bome Patten '52 owes much of its genesis to Alcoholics Anonymous. It therefore seems appropriate to recall here that one of the co-founders of this unique organization was a graduate of Dartmouth: Dr. Robert Holbrook Smith '02. Anonymity of course goes to the heart of AA, and except for the fact that in 1949 Dr. Bob, as he was known within the group, chose to break his own zealously guarded anonymity in paying tribute to his wife's considerable part in founding AA, this fact might never have become publicly known.

Curiously, no biography of this remarkable man seems to have been written. What little is knowable must be pieced together from a few public sources: occasional mentions in the '02 class notes and several tributes which appeared in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE after his death in 1950; obituaries in prominent newspapers; an occasional magazine article on AA; and a scanty biographical sketch in a 1951 memorial issue of the Grapevine, the newsletter of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Born in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, he came to Dartmouth in 1898, like many another freshman "a rebellious young colt" finally "free of his parents' restraining supervision," as the writer of the Grapevine sketch recorded. In Hanover he quickly gained fame among his classmates "for a capacity for drinking beer that was matched by few and topped by none." Nevertheless, he was "a good student in spite of himself" and completed a pre-med course in 1902. After three years of desultory employment he entered first the University of Michigan Medical School and then Rush Medical College in Chicago and received his M.D. degree in 1910. For the following 41 years he practiced medicine in Akron, Ohio.

It was at Rush that alcoholism assumed the proportions of a potential disaster for Dr. Bob; one prolonged drinking crisis required him to withdraw from school for several months and to postpone his degree while he dried out. The problem persisted, indeed worsened, throughout the years of medical practice in Akron and was on the point of irretrievably destroying his professional career until one day in May 1935, when a benign fate brought Dr. Bob and Bill W. together.

The two had much in common. A New York stock broker temporarily in Akron to conduct a proxy fight. Bill W. was also an ex-Vermonter - and also a near-hopeless alcoholic. Out of Dr. Bob's and Bill W.'s first conversation about their shared plight the idea of Alcoholics Anonymous was born. "You see," Bill W. later wrote, "our talk was a completely mutual thing. . . . I knew I needed this alcoholic as much as he needed me. This was it. And this mutual give-and-take is at the very heart of all of AA's Twelfth Step work today.... The final missing link was located right there in my first talk with Dr. Bob."

Impressions of Dr. Bob vary. Whatever else, he was a transplanted Vermonter all the way. He "spoke with a broad New England accent," one Ohioan noted, and another characterized him as a "cadaverous-looking Yankee," a "gruff person, a bit forbidding." But beneath the New England granite there was also that characteristically elusive, understated sense of humor of the Northeast Kingdom. All agree that he was an accomplished story-teller who could tell a riotous story with absolute Vermont deadpan. When asked perhaps a shade too solemnly to outline his ambitions, he did so: "to have curly hair, to tap dance, to play the piano, to own a convertible." And he wrote to his Class Secretary during the last year of his life: "I hope to get to Cleveland July 30 to address an AA meeting at which 15,000 are expected from all over the world." And he added, characteristicallv, "That's a lot of drunks."

One of the most appropriate though long-posthumous tributes to Dr. Bob occurred in the place where it all began. Some years ago a newly appointed faculty member, already a member of Alcoholics Anonymous, arrived in Hanover to begin his teaching duties. In alien territory, he looked immediately for his first line of defense, the customary AA listing in the phone book. Nothing. Concerned, he did a little discreet inquiring. Still nothing. Windsor, yes; Woodstock, yes; but apparently no AA activity of any kind in Hanover. On the official roll of his first class he noted that the class numerals of one student were those of a class that had graduated two years previously. "What happened." he casually inquired of the student, "did you get drafted or something?" "No, Professor," came the reply, "I dropped out of college for two years because my life had become unmanageable."

The language was verbatim from Step 1 of Alcoholics Anonymous! "Are you a member of AA?" the professor asked. "Yes," said the student. "Are you, too?" The two alcoholics soon found a third, then a fourth, then a flood; lunch meetings were organized, and not many months later the Hanover Friday Night Meeting was formed. Today, some years later, that meeting is attended by 30 to 40 people each week; there are five meetings of AA per week in Hanover (some of them public), two per week in Norwich, and many others in Lebanon, White River, and other Upper Valley towns. They are regularly attended by all sorts and conditions of people, the professor reports: lawyers and laborers, students and farmers, clergy and faculty members, and "poor desperate people who can hardly read or write." The local rate of success is high, he says, well over 60 to 70 per cent.

Dr. Bob '02 would have liked that.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

June 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureYesterday's Glories Tomorrow's ?

June 1977 By JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

FeatureThey Also Went Forth

June 1977 -

Feature

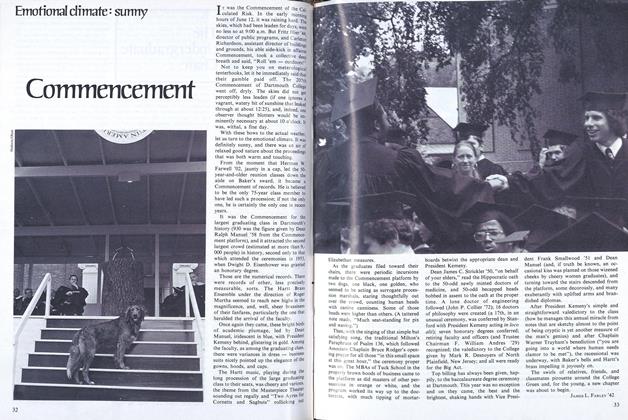

FeatureCommencement

June 1977 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Valedictories

June 1977 By JOHN FINCH -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1977

R.H.R.

-

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

May 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on an expatriate's look homeward and on a bookman in a vast, sparsely inhabited region

October 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksAn Attendant Lord

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on some gentlemen songsters, with an aside on "antique and toothless alumni"

December 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

MARCH 1978 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

Books"The Geology of New Hamshire"

December, 1925 By E. D. E. -

Books

BooksFREEDOM OF SPEECH BY RADIO AND TELEVISION.

APRIL 1959 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksHELIX,

October 1947 By Sidney Cox -

Books

Books100 AMERICAN POEMS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY.

NOVEMBER 1966 By THOMAS CARNICELLI -

Books

BooksEASTWARD THE SEA.

JULY 1959 By W. R. WATERMAN -

Books

BooksThe Tragedy of a Gentleman Activist

MARCH 1978 By WILLIAM McCURINE, JR. '69