MUSIC IN THE NEW WORLD by Professor Charles Hamm Norton, 1983. 122 pp., $25.00, cloth

When I was young, the history of music tended to be naively thought of in terms of the great men who made it; the view that it was an interaction between the private and the public life was suspect. Times have changed. If man, as Sir John Davies put it during the High Renaissance, is "a proud and yet a wretched thing," we have, as humanism has soured, become more conscious of his wretchedness, less of his pride, and have increasingly come to think of him; and of the languages in which he makes himself manifest, as "structurally" conditioned. Though the pendulum may have swung too far from a belief in man's potential, there are some consequences of the swing that qualify as assets. One is the admission that music exists only in the context of man-made societies, wherein it does things to us at many levels. "Pure music is not just an implausible concept; it is an impossibility.

Writing this new history of American music, Charles Hamm is always concerned with what-, at a given time, music is, and what its specific functions in the community it serves are. Good, bad, and indifferent music will coexist at all levels aristocratic, bourgeois, and demotic in contexts both rural and urban. All these musics not only coexist but also interrelate, and in investigating these interrelationships, any musicologist today becomes also an ethnomusicologist. The central merit of Hamm's book is that it considers music was as a creative activity in the then-present; and, complementarily, in dealing with a current moment, is concetned not with what might have happened or ought to happen, but with what in fart.occurs, here and now, as races, culancl genres commingle. Our apparnt musical confusion is seminal. "The province of the historian is to find out, not what was," Thoreau wrote, "but what is."

While Charles Hamm does much to "present" the past, he would certainly not deny that the task is difficult, and not merely for the obvious reason that there's so much of it. His overt intention is not to make value judgments but to reveal the unfolding pattern of American musicmaking. Yet implicit judgments cannot be avoided and, since art is "news that stays news," many of them have already been made by history. Given a few modifica- tions of emphasis, this works with art mu- sic of the past, and in dealing with more recent manifestations which "history" hasn't had time to evaluate, one at least has the yardsticks of precedent.

In the fields of pop music the matter is trickier, especially since most of the music is notated inadequately or not at all. Is value here to be equated with efficacy, in the way that Amerindians, for instance, judge music by its therapeutic results? The multifaceted realms of pop music are bedevilled by this kind of ambiguity. Commentators shilly-shally between the criteria of a number's position in the "charts" and its intrinsic merits, believing that a commercially successful number must presumably fulfil its social function with maximum efficiency, while being teased by a feeling that commercialization might be a betrayal. In the long run, there's nothing to do but admit that the relation between social efficacy and artistic value is always complex: so one must assess each case on its merits, which takes time. For this reason, among others, the comprehensive history of music must inevitably be superficial and in some ways misleading. Charles Hamm's history misleads much less than most.

In areas that are more sociological and anthropological than musical, this book is always useful and often revealing. Hamm quotes copiously and astutely from con- temporary documents bearing on early American musics both polite and demotic; especially pertinent is his backdrop to shape-note music and to American marching bands. He's good at the anthropology of Tin Pan Alley, but he is less convincing when he comes to assess not the quality but the character of the individual composers of Broadway. At any meaningful level, that could be achieved only with fairly detailed analysis, for which he has no space; so we trundle over the surface of the vast industrial landscape, taking in the sights, but not learning much about the human creatures that inhabit them.

The problem, though less acute, still exists with the "art" composers. I don't quarrel with the fact that Stephen Foster gets more space than Aaron Copland, since the memorability of Foster's songs is a creation of genius, not just talent, and the songs are a profoundly American testament which has lasted a hundred and fifty years; we can't be sure that Copland's will prove that durable. I'm less happy that 19th century worthies like Paine, Foote, and Chadwick are discussed in relation to their background, whereas pioneering eccentrics like Ornstein and Rudhyar don't rate a mention, and even the great Ruggles gets no more than citation in a roll-call. These men are at the heart of the American Experience in a way that the Europeanized exponents of the Genteel Tradition are not. Their omission is the more surprising because Hamm has no doubt that Ives is the first major American composer and perhaps the first composer of democratic principle; moreover, he writes emphatically of Conlon Nancarrow, of Cage, and of that great old aboriginal of the Californian deserts, Harry Partch.

Another Californian, Lou Harrison, is not mentioned; which seems regrettable, not merely because he's a fine composer but also because, since Partch's death, Harrison has assumed his mantle, and acquired documentary as weir as intrinsic significance. I don't want to indulge in a puerile game of who's in, who's out except insofar as it does matter, a history book being inevitably selective, on what principles admissions and omissions are decided. Just occasionally Hamm seems to approach "art" composers with a nervous shuffle more appropriate to stars of the pop world, citing the number of prizes they've won as though that were itself a qualification. It tells us something about the qualities an intellectual art-world is looking for at a given moment, just as the charts tell us something about popular prejudice and preconception. I wish Charles Hamm had been a shade more courageous in looking behind facades, though I have nothing but respect for his comprehensive generosity of spirit. We're grateful for a book that, in helping us to understand America better also helps us to understand ourselves.

Wilfrid Mellers, Professor Emeritus of Muskat the University of York in England andauthor of, among many other works, Music in a New Found Land, was recently a visitingprofessor in the Dartmouth music department fortwo terms.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe View from the Women's Locker Room

June 1983 By Agnes Kurtz -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

June 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

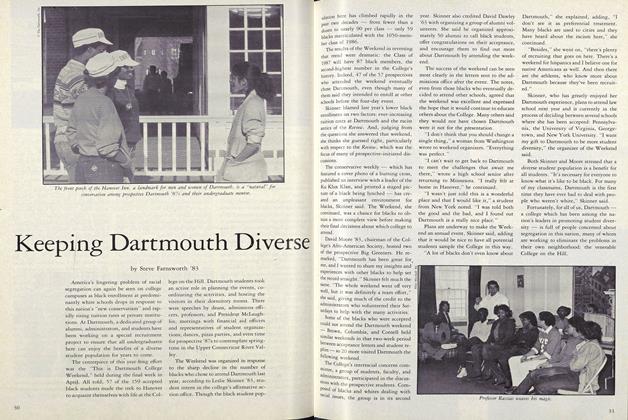

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

June 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83 -

Feature

FeatureJustifiable Pesticide

June 1983 By Robert Bell '67 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Ledyard's Wake

June 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz '83 -

Feature

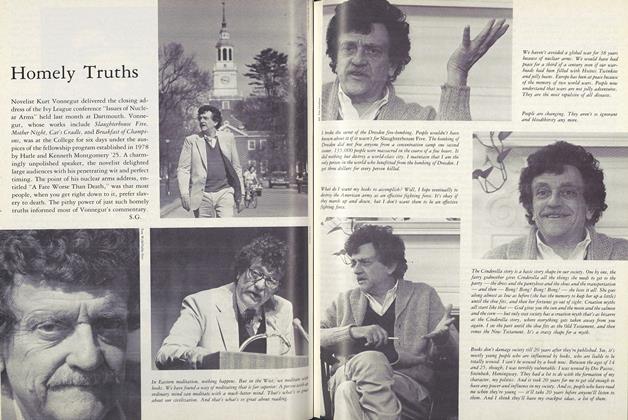

FeatureHomely Truths

June 1983 By S.G.

Books

-

Books

BooksJAPAN: IMAGES AND REALITIES.

JANUARY 1970 By ALMON B. IVES -

Books

BooksINTRODUCTION TO FINITE MATHEMATICS

March 1957 By BANCROFT H. BROWN -

Books

BooksTHE GEOLOGY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, PART I — SURFICIAL GEOLOGY

November 1952 By E. D. Elston -

Books

BooksSPARROW HAWKS

October 1950 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksGAUGING PUBLIC OPINION

June 1944 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Books

BooksNO PLACE TO HIDE

January 1949 By Herbert F. West '22