SHAKESPEARE AND THE SHAPES OF TIME by David Scott Kastan University Press of New England, 1982. 197 pp., $25.00

What, then, is time? I know well enough what it is, provided that nobody asks me; but if I am asked what it is and try to explain, I am baffled.

Augustine, Confessions

One of the (many) traumas I went through in growing up was learning to tell time. Children no longer have to learn to tell time. They simply read the numbers on a digital clock. The words "clockwise" and "counterclockwise" will have no meaning to most people by the end of this century. Our perceptions of time and of its passing are changing. If we vaguely sense a past and are remotely aware of a future, we are overwhelmed by a present, a now.

Few will be surprised to learn that Shakespeare was acutely aware of the force of time and its passage ("time" and "times" occur 1366 times in the canon). Fewer still will have seen, as David Kastan does, time as the shaping force behind Shakespeare's histories, tragedies, and romances.

In the Middle Ages, the bells of churches tolled the canonical hours, reminding Christians of the passage of time, a passage that would lead them to death and to an eternity of bliss in heaven. In the drama of the Middle Ages, in the Corpus Christi cycle, "human time historical time is circumscribed by its supra-historical limits of Creation and Judgment .... The finite progess of time is embedded in a timeless matrix of eternity."

Not so the Renaissance. Those church bells gave way to clocks that rang the hours and quarter hours away, dividing time into segments of the present, not celebrating but lamenting its passage. It is in and of this time that Shakespeare wrote his plays. Kastan's title, taken from 2 Henry IV, is elucidated in his thesis. Quite simply, Shakespeare's plays are structured, are shaped, by their attitudes toward time.

The history plays are open-ended. They do not begin and end; rather, they start and stop. Each reign is "a mere episode carved from the continuum of human time," making us "confront our fragile existence as 'time's subjects' [again 2 HenryIV] released in a world of contingency and flux." Even as Henry V proposed to Katherine, Princess of his newly conquered France, "Shall not thou and I, between St. Dennis and St. George, compound a Boy, half French, half English, that shall go to Constaninople and take the Turk by the Beard," the play's epilogue, a scant folio page away, reminds us that Henry VI, "whose state so many had the managing," not only lost France, but brought about the Wars of the Roses.

Time in the tragedies is by no means open-ended. Their structure, as they "witness the horror and mystery of human suffering," is closed. Each isolates and confines "the tragic hero within the limits of his own mortal condition. ... At the heart of tragedy is the realization that death and destruction are inescapable."

While Kastan sees the closed structures of the tragedies as utterly pessimistic, that pessimism "cannot be allowed to slide into nihilism. . . . Lear's pain is itself the measure of achieved value. Lear has learned all that can be known about a love that makes breath poor, and speech unable.' "

The only force that can defeat time, something we all know, but something we need to be reminded of constantly, is love, and it is in the structure of the romances, Shakespeare's last plays, that Kastan finds love to be most powerfully felt. These plays "direct us beyond the tragic, demanding that we see beyond time's annihilating effects beyond suffering and loss to forgiveness and reconciliation." In these plays characters are quite literally reborn as they discover and, as importantly, accept, "the miraculous capacity of the human spirit to forgive and to love."

Though I would cavil with a thesis that turns Richard 111 into a romance, leaves Macbeth's unclosed structure as an excep- tion proving the rule, and, I suppose, transforms Love's Labour's Lost into a histo- ry play, Kastan's book is a well-written and lively reminder that, as Hotspur tells us in 1 Henry IV, we "ride upon a dial's point." We know all too well where we're going. The "victories we win come not from where we go," Kastan concludes, "but how for there is only one direction though many ways to ride."

Professor of English at St. Lawrence University, Thomas Berger, like David Kastan, is bot a Shakespearean scholar and a committed runner.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Ladieees and Gentlemen.

September 1983 By Jim Tonkovich '68 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

September 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

September 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

September 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

Feature"Those Who Miss The Joy, Miss All"

September 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

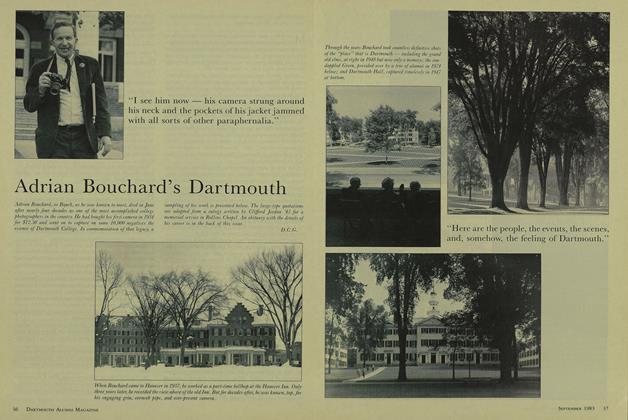

FeatureAdrian Bouchard's Dartmouth

September 1983 By D.C.G.

Thomas L. Berger '63

Books

-

Books

Books"Quinze Contes Franjais,"

APRIL 1930 -

Books

BooksA mimeographed report

APRIL 1932 -

Books

BooksTHREAD OF SCARLET

May 1939 By E. P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksSTUDY-AND WIN

December 1946 By Louis P. Benezet '99. -

Books

BooksOF A HUNTER, NOW!

May 1945 By Vernon Hall Jr. -

Books

BooksPERCEPTION AND MOTION.

MARCH 1964 By VICTOR E. McGEE