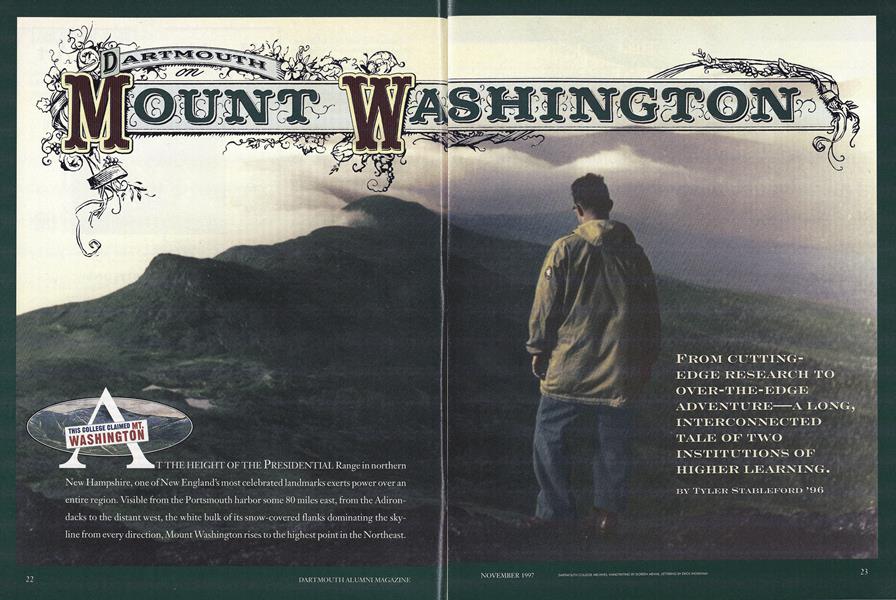

AT HEIGHT OF THE PRESIDENTIAL Range in northern New Hampshire, one of New England's most celebrated landmarks exerts power over an entire region. Visible from the Portsmouth harbor some 80 miles east, from the Adiron to the distant west, the white bulk of its snow-covered flanks dominating the skyline from every direction, Mount Washington rises to the highest point in the Northeast.

The mountain 6,288 feet of forest, alpine gardens, and blocky talus is more than just a peak to bag. Smaller than nearly every major peak in the West, Mount Washington holds the unique title of being the world's smallest big mountain. Its summit is lower in elevation than many downtown streets in, say, Colorado. But don't let its diminutive elevation fool you, for Mount Washington is never a peak to be underestimated. "Mount Washington has considerably greater objective risk than other mountains," asserts Outing Club historian David Hooke '84, in the calculated parlance of serious mountaineers. "It is the ultimate challenge."

The summit cone, rising far above the treeline, is home to the largest area of Arctic conditions in the East and some of the severest weather anywhere. With that weather, and with an unusually large endowment of snow chutes, ice gullies, exposed rock, and Arctic flora, Mount Washington has become a legendary arena for both academic research and necky adventure. A single college, naturally built on both academics and adventure, has led the way for much of the peak's scientific exploration and mountaineering feats. Mount Washington bears a particular stamp of human stewardship and exploration, the mark of a long legacy of fascination that can belong to only one institution: Dartmouth.

Dartmouth owns more than eight acres of Washington's summit, the remains of an enormous land holding that once included 59 acres of summit, the Cog Railway, and the railway's base station. But these are just the beginnings. The College has been a steward for reasons much greater than a land deed. Located 90 miles northeast of Hanover, the mountain has served as a cutting-edge research base for professors; a weekend getaway for countless students; and a testing ground for extreme skiers, Himalayan climbers, and pranksters.

Geology professor Charles Hitchcock in 1870 was the leader of the first party ever to spend a winter living on the summit and recording its weather. His expedition started a long tradition of Dartmouth research on the peak, a history that includes the founding of the Mount Washington Observatory and the measuring of the highest wind speed (231 mph) ever recorded on earth.

Olympic ski jumper Charley Proctor '28 introduced extreme skiing to America when he became the first daredevil to descend the precipitous Tuckerman's Ravine headwall a feat many of today's students still back nervously away from. Dick Durrance '39 took three first-place finishes in the legendary summit-to-base Inferno ski race, before the race was declared too treacherous to continue. Several students made their summer wages as workers on the summit-bound Cog Railway and as reporters for the historical summit newspaper. Students continue to work on the mountain on the trail crews and in the high huts of the Appalachian Mountain Club. Dartmouth holds title to many of the mountain's legends.

EARLY NATIVE AMERICANS living near the peak named Mount Washington Agiocochook. According to their beliefs, ascending to the summit would bring the penalty of death. In a sense, that belief is not wholly false. In the last two centuries of exploration, 132 people have died on the mountain, leaving a casualty list longer than that of any other peak in the country. And here, too, Dartmouth has left its mark. On the weather-torn slopes, the wind still whispers over the souls of two students who remain forever with the mountain. On Thanksgiving weekend in 1928, freshman Herbert Young '32 was hiking with other Outing Club friends, going east to west over the peak in harsh wind and sleet. Just above treeline on the western slopes, Young collapsed. His friends hurried down to get a sled and additional hands. When they returned several hours later, however, Young had died of hypothermia. Peter Friedman '83 succumbed to a more violent fate in 1980 when he fell a full rope length while ice climbing in Huntington's Ravine, ripping out his anchors and sending him 500 feet down to the ravine floor.

In the words of Mount Everest pioneer Barry Corbet '58, who trained on Washington as a student, "We went to Mount Washington to live dangerously. We wanted to learn about ice climbing, and that was the place to do it."

But Dartmouth's involvement on the mountain is not only of risk-seekers. To highlight only these few ignores the countless numbers who visit the peak in all seasons, exploring the alpine gardens in July or skiing the remote Gulf of Slides in springtime; the faculty and students from physics, earth science, and geography who take to the mountain each year to field-test their classroom work or to conduct research under Arctic conditions. Together, the academic exploration and adventures on this peak reflect the fascination and love of a certain breed of people. Perhaps nowhere else are the historical, scientific, and cultural connections so strong between a college and a mountain.

"A LITTLE BIT SCARY" AND OTHER UNDERSTATEMENTS

ski champion and member of two Olympic ski teams, described the race as "a little bit scary." Dartmouth holds a special title to Mount Washington. Because for nearly every skiing, climbing, or buffoonery feat on the mountain, Dartmouth students, somehow, were there. In March 1913, Dartmouth Outing Club founder Fred Harris '11, Joseph Cheney '13, and Carl Shumway' 13 constituted the first collegiate club to ascend and descend the mountain on skis. On April 11, 1931, Charley Proctor '28 made his famous first descent of the formidable headwall of Tuckerman's Ravine, almost certainly the steepest slope ever skied at that time. And during the hot but short-lived history of the Inferno downhill race from summit to base during the 1930s, Dick Durrance took first place three times during the race's seven-year history. Dubbed a "suicide race," competitors skied straight off the summit toward Tuckerman's Ravine, barreled over the headwall and then down through the tight trees to Pinkham Notch base. Durrance, a four-time collegiate

"The headwall is a cornice, and it grows very steep," Durrance says today. "To run a race over it is pretty hairy."

For a number of years, Dartmouth also went head to head against skiing rival Harvard during spring races lower in the ravine, often held on the tight ski chute now called Hillman's Highway. The origin of that route's name? Dartmouth downhiller and "famed wild man" Harold Hillman '40.

THE COG RAILWAY

For more than a decade, Dartmouth was one of the largest landowners on the mountain. Its holdings included the Cog Railway business and its eastern base station, plus the entire 59 acres of summit and summit buildings. A gift from a dying alum, these holdings were one man's way of saying thank you to the College.

Colonel Henry Nelson Teague, class of 1900, owned and operated the Cog Railway for 20 years, beginning in 1931. When the 1938 hurricane destroyed $60,000 of railroad trestles and threatened to put Teague out of business, the College loaned him several thousand dollars to help rebuild. Although Teague promptly repaid the loan, he never forgot the favor. When he died in 1951, he left his entire holdings to his alma mater.

For more than a few Dartmouth students, the Cog Railway was a perfect summer job. Paul Dunn '32, working under Teague, became the first college-student railroad engineer to drive the passenger trains to and from the summit.

Dartmouth sold the railway and much of the summit in 1962, but held on to 8.2 acres on the southwest side. The College leases this land to a television and radio network for $1,000 a year. Meanwhile, the College is working with the White Mountain National Forest and the Appalachian Trail Conference on creating a permanent right-of-way over part of Dartmouth's land one of the last three places in New Hampshire where the Appalachian Trail crosses private land.

"THE WORLD' S WORST WEATHER"

With an average yearly temperature of a frigid 27 degrees, and wind speeds that gust to hurricane strength on average once every third day, Mount Washington has earned the deserving title of "Home of the World's Worst Weather." But for several hardy Dartmouth researchers, the mountain has simply been called "home."

Geology professor Charles Hitchcock made headlines in 1870 and 1871 as the leader of the first party ever to spend a winter on the summit. Prior to that time, no one had dared endure Washington's winter weather for more than a brief outing. Hitchcock and his colleagues established a makeshift winter weather observatory in the Cog Railway summit depot, and telegraphed their daily recordings to the Dartmouth geology department. He and one of his partners had trained for the endeavor by spending two months in the summit house on Mount Moosilauke the previous year, daily recording the weather conditions until a winter tempest sent them running for lowland shelter at the end of February.

Official winter weather observations on Mount Washington ceased two years after Hitchcock's first expedition. It wasn't until 1932 that another team wintered on top, and again Dartmouth was there. That year Bob Monahan '29, Joe Dodge '55H, and Alex McKenzie '32 gathered funds from several large science foundations to establish the permanent Mount Washington weather observatory that still exists today.

During that first winter of 1932-33, Monahan, McKenzie, Sal Pagliuca, and a catnamed Ticky volunteered to spend the long cold months on top. They witnessed other rarely seen phenomena. The men had no replacements, and only occasional visits from College friends and professors, so they took no time off. Plus, says McKenzie, "we had neither skis nor crampons, so we had to stay. There was no sort of going up and down hill." McKenzie, in fact, spent only two days off the summit that winter, during an emergency trip to a dentist for his aching gums.

McKenzie made world-record fame in 1934 when, during his second year at the observatory, a storm on April 12 gusted well over 200 miles an hour. At 1:31 in the afternoon McKenzie and his crew recorded two gusts of 231 miles per hour a speed that has never been topped anywhere in the world. McKenzie and the others actually had to venture into the winds every hour or so during the storm to clear the rime ice from the anemometer pole. More than six decades later, McKenzie, from his home in Eaton Center, New Hampshire, still recalls the desperate struggle to keep the instruments working during the storm: "We were onto the roof in winds of 150 miles per hour," he says, "and when we climbed the ladder up to the roof ridge, all hell turned loose. We had to grasp anything we could."

BETWEEN DARTMOUTH AND THE MOUNTAIN

Possibly the only person without a college degree of any kind to have won such esteem from Dartmouth, high-school graduate Joe Dodge was the overseer of Pinkham Notch base on the mountain's western slope for 33 years. Friend to Dartmouth skiers, climbers, researchers, and observatory volunteers, Dodge was the permanent liaison between Dartmouth and the mountain. He helped found the East coast ski patrol during the Dartmouth-Harvard races in Tuckerman's Ravine, supplied Robert Monahan and Alex McKenzie during their fledgling winter in the summit observatory, and rescued more than one Dartmouth student from the mountain's wintry clutch. At his son's graduationin 1955, sitting alongside co-honoree Robert Frost, Dodge earned an honorary degree from the College. In the words of President John Sloan Dickey, who conferred the master of arts degree:

"Onetime wireless operator at sea, longtime mountaineer, student of Mount Washington's ways and weather, you have been more than a match for storms, slides, fools, skiers, and porcupines. You have rescued so many of us from both the harshness of the mountain and the soft ways leading down to boredom that you, yourself, are now beyond rescue as a legend of all that is unafraid, friendly, rigorously good, and ruggedly expressed in the out-of-doors. And with it all you gave this College a great skiing son. As one New Hampshire institution to another, Dartmouth delights to acknowledge you as master of arts."

STILL HIGHER LEARNING

Today, Dartmouth professors continue to use the mountain as an outdoor classroom and as a personal research base. Geography professor Laura Conkey takes her students to the 14-square-mile Alpine Gardens covering Mount Washington and its neighboring peaks each summer, where they map the locations of rare plant and animal species. Earth science professor Dick Birnie '66 has studied the mountain for more than 20 years, most recently as part of a remote-sensing project to detect changes in global weather patterns.

In the end, really, this is what Dartmouth's connection with Mount Washington is all about: pushing the limits of self, of nature, of knowledge.

FROM CUTTINGEDGE RESEARCH TO OVER-THE-EDGE ADVENTURE A LONG, INTERCONNECTED TALE OF TWO INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER LEARNING.

No one will ever surpass Dick Durrance '39's three victories in the "Inferno." The summit-tobase ski race was cancelled because it was too dangerous.

When the Cog Railway blew down, Dartmouth loaned Henry Teague '00 money to put the train back on track.

Clearing rime ice from weather instruments was just part of the job for Alex McKenzie '32, both on good days and in record-setting wind storms.

Kevin Hand '97 climbs Huntington Ravine's Pinnacle Gully, a testing ground for Dartmouth's most serious climbers.

Dartmouth geography students map the Alpine Garden's flora.

"Mount Washington from Mann Hill"

GANOES IN THE GLOUDS Dartmouth students took title to a unique honor in 1976: During the country's bicentennial celebrations on July 4, an eager band of students made the first "portage" of two canoes to the mountain's summit. Starting on the western base near the Cog Railway, the men and women carried two large canoes over their shoulders up, above treeline to Lakes of the Clouds Hut, where they A made the first-ever (though somewhat less than legal) canoe crossing of the. small lakes; then continued on to the summit for a patriotic celebration complete with a quarter-keg of beer that a student had carried for the. journey.

WORK Dartmouth students have been an almostconstant presence on Mount Washington. They have been Appalachian Mountain Club hut crew members, working as zany innkeepers and skilled rescue team leaders at Lakes of the Clouds Hut. They have built rock staircases and cairns as pare of the legendary Appalachian Mountain Club Trail Crew. They have worked on Mount Washington as part of A.M.C. departments of research, volunteer training, and education.

ENDLESSLY SCHLEPPING SCHLITZ Of all the skiing feats, it is an old black-and-white movie that has become a permanent part of Dartmouth history. Nearly every student on campus today has seen the film at least once: Schlitz on Moun Wasbington. A short 1930s comedy about a German doctor who finds himself engulfed by a riotous series; of misadventures and ski daredeviling, the film actually does; not feature any Dartmouth skiers. But after being discovered by the Outing Club in the 1960s, the film-has been shown religiously after Freshmen Trips dinner at Moosilauke Ravine I-, Lodge every year since. It's narrated by Lowell Thomas Sr. '77H.

HIGH PRIESTS OF JOURNALISM Dartmouth students refined their journalism skills as writers for the country's: only summit-published newspaper, Among the Clouds. (Operated every summer be- tween 1874 and 1908, the paper was an apprentice ground for reporters Ghanning Cox'01 and John Bart lett '11, who later became governors of Massachusetts arid New Hampshire, respectively.

BIG MOUNTAIN TRAINING Mount Washington was, and still is, a testing ground for aspiring mountaineers, and no place has provided better training than Huntington Ravine's, die steep, ice-choked basin north of Tuckerman's. According to Himalayan climber Andrew Harvard '71, climbing in Huntington's was as big an alpine test as anything else in the country. "Huntington's Ravine was the gathering place for big-mountain mountaineers," he says. "The weather on Mount Washington really approximates the weather you get on a high Himalayan or Alaskan peak." Using skills learned on Mount Washington, Dartmouth climbers have ventured to high mountain ranges world wide.

COME HELI OR HIGH WATER Photojoumalist Doug-aid Mac Donald '82 made a skiing first (and also, perhaps, a last) in 1984 when helicopter-skiing trip on Mount Washington for Yankee magazine. MaeDonakd and the skiing crew took two flights to the summit on a clear March day, then schussed all the way down to the base. The ski company was testing a venture heliskiing business, but the operation quit almost as soon as it had begun.

LOFTY ART Art history professor Bog McGrath uses art from Mount Washington and other White Mountain Peaks in his freshmen seminar, "Nature and the American Imagination." "Dartmouth is the best-known repository of White Mountain .Art," McGrath boasts, "including many views of Mount Washington." The Hood Museum of Art displayed this collection in its 1988 show, "A Sweet Foretaste of Heaven."

TYLER STABLEFORD '96 first skied Tuckerman's headwall in the spring of 1997. He lives among really big mountains in Colorado, where he is photo editor at Climbing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

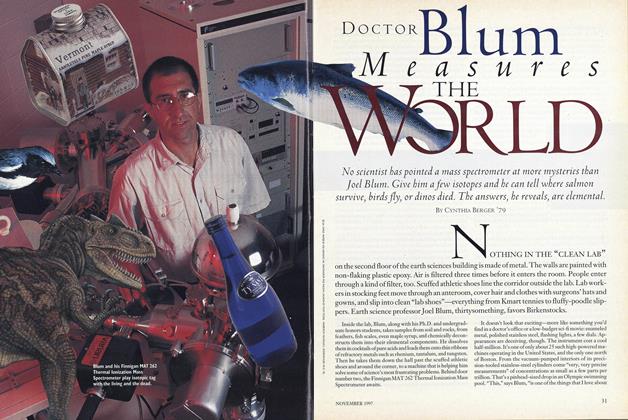

FeatureDoctor Blum Measures the World

November 1997 By Cynthia Berger '79 -

Feature

Feature"Hi. My Name's John. I'm a Zero."

November 1997 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Article

ArticleThe Truth, The Half Truth, and Nothing of the Truth

November 1997 -

Article

ArticleThe President Steps Down

November 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Collis Silverware Mystery

November 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleLiving Well by Doing Good

November 1997 By James O. Freedman

Tyler Stableford '96

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2006 -

Article

ArticleThe True Story Of the 1939 K2 Disaster

October 1993 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

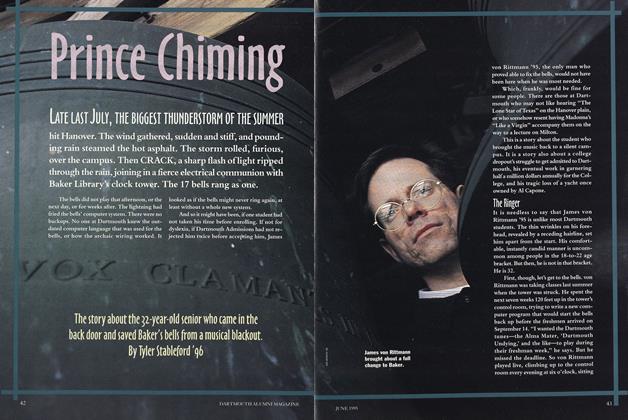

FeaturePrince Chiming

June 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Cover Story

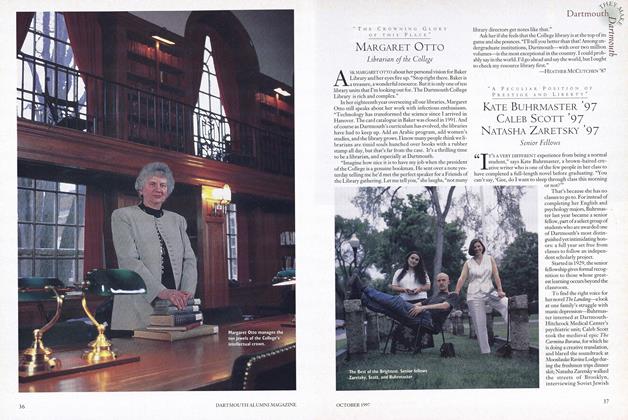

Cover StoryKate Buhrmaster '97 Caleb Scott '97 Natasha Zartsky '97

OCTOBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCarl Wallin Bary Harwick '77 Ellen O'Neil '87 Sandy Ford-Centonze

OCTOBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleRookie of the Year

May 1998 By Tyler Stableford '96

Features

-

Feature

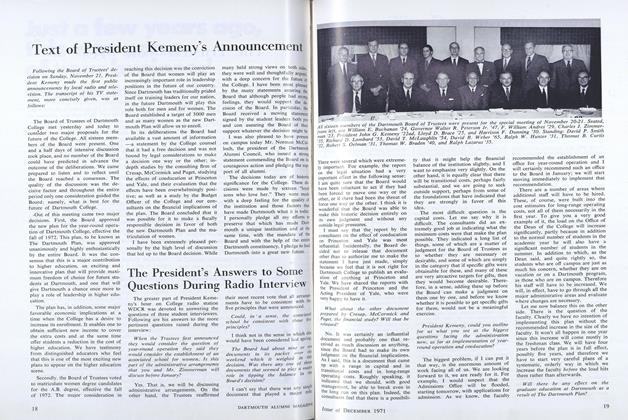

FeatureText of President Kemeny's Announcement

DECEMBER 1971 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMara Rudman '84

March 1993 -

Cover Story

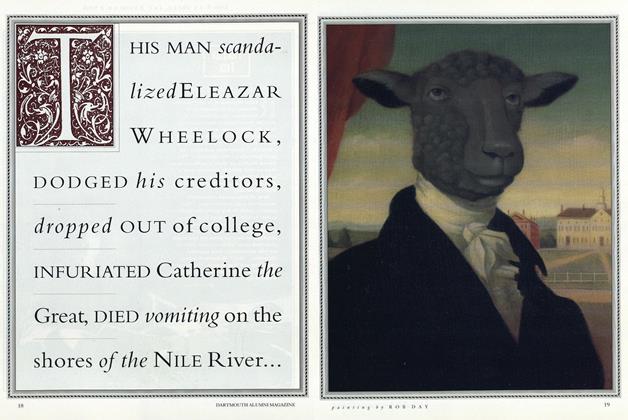

Cover StoryThis Man Scanndalized Eleazar Wheelock

June 1993 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Feature

FeatureThirty Years After

June 1957 By RICHARD W. HUSBAND '26 -

Feature

FeatureSome People Are Good Skiers

February 1975 By V.F.Z.