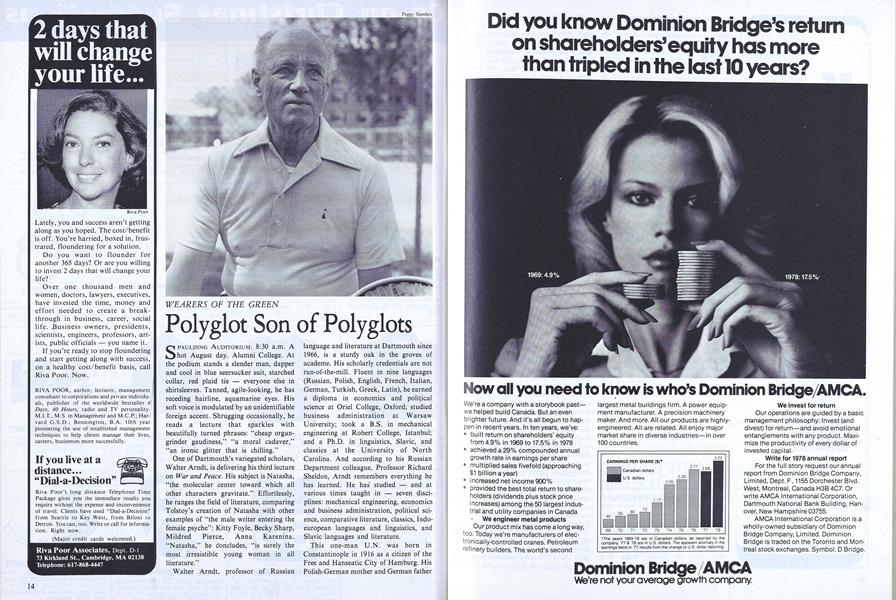

SPAULDING AUDITORIUM. 8:30 a.m. A hot August day. Alumni College. At the podium stands a slender man, dapper and cool in blue seersucker suit, starched collar, red plaid tie — everyone else in shirtsleeves. Tanned, agile-looking, he has receding hairline, aquamarine eyes. His soft voice is modulated by an unidentifiable foreign accent. Shrugging occasionally, he reads a lecture that sparkles with beautifully turned phrases: "cheap organgrinder gaudiness," "a moral cadaver," "an ironic glitter that is chilling."

One of Dartmouth's variegated scholars, Walter Arndt, is delivering his third lecture on War and Peace. His subject is Natasha, "the molecular center toward which all other characters gravitate." Effortlessly, he ranges the field of literature, comparing Tolstoy's creation of Natasha with other examples of "the male writer entering the female psyche": Kitty Foyle, Becky Sharp, Mildred Pierce, Anna Karenina. "Natasha," he concludes, "is surely the most irresistible young woman in all literature."

Walter Arndt, professor of Russian language and literature at Dartmouth since 1966, is a sturdy oak in the groves of academe. His scholarly credentials are not run-of-the-mill. Fluent in nine languages (Russian, Polish, English, French, Italian, German, Turkish, Greek, Latin), he earned a diploma in economics and political science at Oriel College, Oxford; studied business administration at Warsaw University; took a B.S. in mechanical engineering at Robert College, Istanbul; and a Ph.D. in linguistics, Slavic, and classics at the University of North Carolina. And according to his Russian Department colleague, Professor Richard Sheldon, Arndt remembers everything he has learned. He has studied — and at various times taught in - seven disciplines: mechanical engineering, economics and business administration, political science , comparative literature, classics, Indo-european languages and linguistics, and Slavic languages and literature.

This one-man U.N. was born in Constantinople in 1916 as a citizen of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg. His Polish-German mother and German father ("Both my parents were polyglots") happened to be in Turkey because his father, a well-known organic chemist, was helping Kemal Ataturk reorganize the univeristy system. Walter had nine years of classical schooling in Wroclaw, Silesia (then Breslau), but when Hitlerism erupted in 1933 his father removed the family to Oxford. Miriam Arndt, Walter's German- Jewish wife, says proudly, "My Lutheran father-in-law was one of the too few people who left Germany without having to."

Walter Arndt appears to be a pocket- size combination of James Bond, Faust, and Dick Whittington. His life overflows with adventure, scholarship, hard work, intrigue, improbable coincidences, good luck, and new beginnings. He was doing graduate work at the University of Warsaw when the Germans marched into Poland. Six months earlier, Arndt had gone to the German consulate, turned in his passport, and volunteered for the Polish army. He was through with his German citizenship forever, and was fairly high on the Nazis' hit list.

Asked about his war experiences, Arndt gives an account that is a monument to understatement. "After the peripatetic campaign of 1939, I escaped from an ill-run German POW camp, spent a year in the Polish underground at Warsaw, chiefly producing lifelike Nazi documents and passes, and finally in 1940 made my way to Istanbul via Berlin. There, in a civilian interlude imposed by Turkish neutrality, I took a degree in engineering at Robert College and resumed intensive study of Russian language and literature."

There he also joined the U.S. intelligence service, first the O.S.S. in Istanbul, then the O.W.I, in the Aegean. He did refugee resettlement work for the U.N. as well. And there he met Miriam Bach, with her flashing smile and quick wit. She was 17, he was 24. He taught her tennis and helped her with her English "and that helped in other ways." They were married in 1945 and spent the next four years trying to get to America. "Europe was out. Our world had been destroyed."

The U.S. quota system admitted 100 imgrants per year from the eastern Mediterranean. "If you had a teaching job," Arndt recalls, "you could come over outside the quota, but you couldn't get a job without an interview and you couldn't get an interview unless you came over. Catch 22." Finally, thanks to the Institute for International Education, a Friends school in Tennessee hired him sight unseen.

Few people have made a bigger leap in life than the four Arndts (two sons had been born in Turkey) made from cosmopolitan Istanbul to the quilting-bee world of Friendsville, Tennessee. They emigrated with a few heirloom oriental rugs, almost no cash, and open minds.

In Friendsville, Arndt taught eighth grade English, typing, bookkeeping, Latin, geography, and history. His salary was $1,000 a year. The Arndts were exotic birds in a town that had never seen a "furriner." The children would run up to him and say, "Talk some Turkey, gobble, gobble, gobble!" The following year they moved on to a better job at another Quaker institution, Guilford College, near Greensboro, North Carolina, but they have never forgotten the warmth and kindness of their first friends in America.

For their parents' 25th anniversary the four Arndt children (two daughters were born in North Carolina) had their father's semi-annual letters to his European relatives bound into a handsome book. It is titled as he signed his letters: All The Best,Walter. But this fascinating book could just as well be called An AcademicPilgrim's Progress, as shown by these examples:

Guilford College, 1950: "A light average teaching load [German, Latin, economics, one business course, and French in summer]. Nothing I can teach is elementary enough; in most of my young people I find no vestige of a scrap of prior knowledge."

University of North Carolina, 1957: "My new job has developed several ramifications, mostly pleasant. ... I am not entirely cooped up in the Slavic field but have been given a little niche in linguistics. ... I have one lecture in the history of the German language, which includes German and late Germanic historical phonology and lexicon, German dialect geography, the evolution of the standard language, and so 0n. ... I hope to add to the curriculum an introductory course in Slavic linguistics, combined with a brief historical sketch in Russian phonology and lexical development. ... My basic stock-in-trade is, of course, the Russian language courses (four semesters) and the lectures on 19th-century Russian literature. These will sooner or later have to be supplemented by a course in Soviet literature please God not by me. My new verse translation of Eugene Onegin (Pushkin) has crept forward as far as two cantos. ..."

Dartmouth College, 1966: "I have accepted a professorship at Dartmouth College, that hoary, gold-plated, self- consciously celibate and erudite little pile of frostbitten ivy on the Connecticut, halfway between Boston and Montreal. [Son David '7O simultaneously matriculated lated at that] sub-arctic ski-and-degree Shangri-la, his incentives being the unrivaled stage and dramatic resources of Dartmouth and the vicinity of a new flame of unprecedented candle-power."

At Dartmouth, Walter Arndt is considered remarkable for many things - his 6:00 a.m. tennis matches; his poems in Playboy (translations of three long ribald ballads by Pushkin and Lermontov); his capacity for getting grants (Fulbright, Ford, Rockefeller, Guggenheim, among others); his honorary Phi Beta Kappa key; and his Bollingen Poetry Prize for the verse translation Eugene Onegin (lustily assailed by Vladimir Nabokov, despite protests from Edmund Wilson, who insisted that Professor Arndt's "heroic tour de force" was far superior to Nabokov's "uneven and sometimes banal translation"); his ignorance of TV ("If there is another Watergate I'll buy a set"); and his widely various metier which embraces everything from glottochronology to intricate metric translations of Goethe and Anna Akhmatova.

His tastes are eclectic. He likes many things Polish, opera, venison, ice cream, Schubert lieder, Winnie-the-Pooh, singing, rowing, Sicily. He dislikes many things German, pomposity, chicken and innards, rudeness, Polish jokes, nationalism. Not closed to anything, shockproof in fact, he is eager to embrace whatever comes. It is difficult to delineate a man of so many parts. Three other voices might be helpful:

Miriam Arndt on Walter Arndt: "If I wrote about Walter it would be just a hallelujah hymn. He's fun to be with, sensitive , kind, has the patience of Job - 35 years of marriage with me proves that - never loses his temper. He just syphons off his anger with his marvelous sense of humor."

Dick Sheldon on Walter Arndt: "Student are dazzled by him, awed by the quality of his mind. Sometimes it's too much for them, but they're fond of him because he .doesn't take himself seriously, is never puffed up. And he's good with young people. On his birthday his Pushkin seminar presented him with a cake - in the shape of a bust of Pushkin - not a common occurrence in the classroom."

Walter Arndt on Walter Arndt: "I was blessed with a certain confidence that I could make fruitful use of my talents and abilities, such as they are. I'm interested in striking the bridge between experience and expression. I'm half a writer and poet who is longing by some miracle to have time to become a whole one. Much has accumulated in this long life that needs saying , and more keeps happening all the time."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

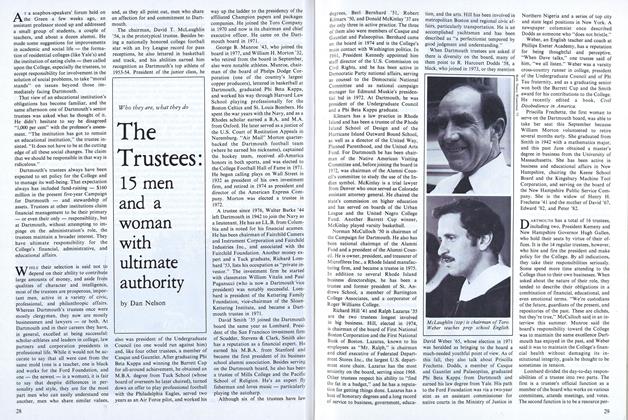

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTwo at the Top: On being a woman, a wife, a partner

October 1979 By Jean Alexander Kemeny -

Feature

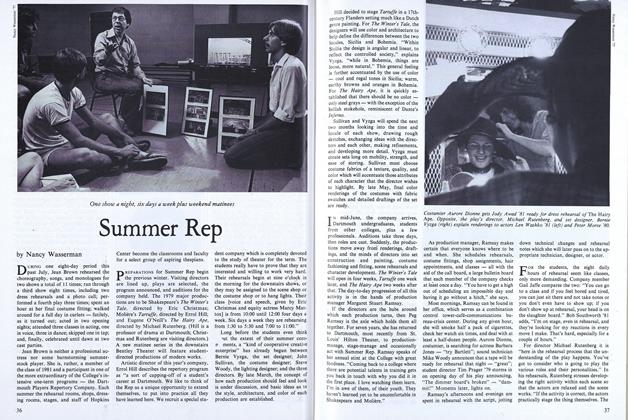

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Article

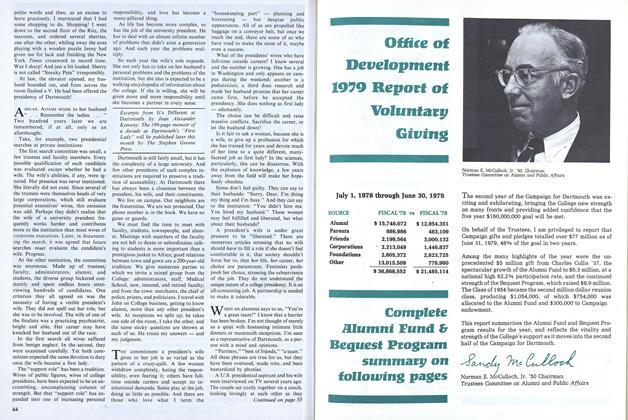

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1979 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

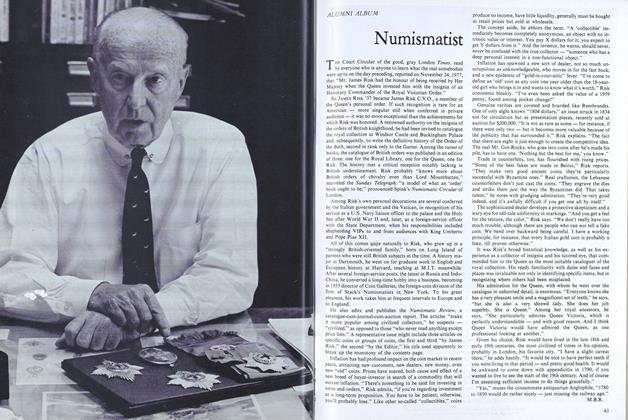

ArticleNumismatist

October 1979 By M.B.R.

NARDI REEDER CAMPION

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to Editor

September 1979 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

March 1980 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

OCTOBER 1982 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

September 1986 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA Full Disabled Life

October 1995 -

Article

ArticleJody's PALS Sing Out

NOVEMBER 1999 By Nardi Reeder Campion

Article

-

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL CAPTAINS FOR 1909

January, 1909 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH SOLDIERS IN FOREIGN UNIVERSITIES

July 1919 -

Article

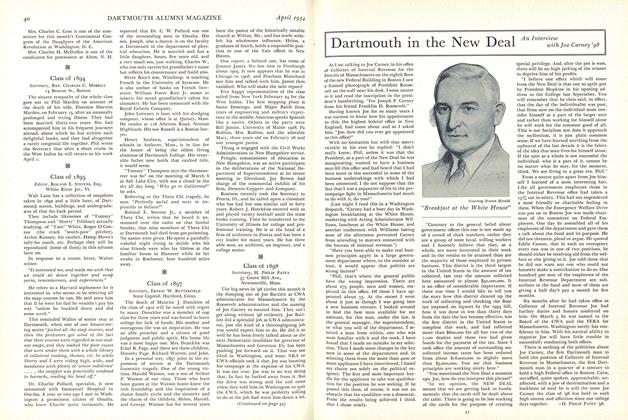

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal

April 1934 By H. Philip Patey '98 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleSTORM WARNING

December 1936 By ROBERT A. SELLMER '35 -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

May 1956 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56