by Professor Jim Jordan Princeton University Press, 1984 251 pp., $55.00.

Near the end of Jim Jordan's scholarly appraisal of Paul Klee's art and thought, he states that "Klee's art. . . lies outside of most standard definitions, challenging our usual generalizations." The statement is so central to Professor Jordan's masterful study that he might well have put it in italics. Of the artists we consider giants of the modern period, the Swiss-born Klee is probably the most difficult to categorize; which is to say that he is one of the most original spirits of the twentieth century. In the attempt to locate him along the spectrum of modern art, many critics and historians have forced Klee into an uncomfortable alliance with the Surrealists, apparently assuming that the haunting and mysterious images of his paintings and drawings spring from the same subliminal urges acknowledged by the champions of Surrealism and related movements. But Klee's imagery that intriguing blend of the arcane and the innocent defies definition and circumscription, and is all the more wonderful for its defiance. What does lend itself to definition and analysis is what Jordan has made the subject of his book: the formal structure of Klee's art.

In a way, Klee was as profound an art critic and theorist as he was an artist, conscious of the many vital currents that connected his own art with that of the more progressive developments of the late nineteenth century and the daring formal experiments of the first decades of the twentieth century. Jordan has realized that an analysis of Klee's relationship to these developments is indispensable to an understanding of Klee's art, and his book is as enlightening in its survey of early modern movements as it is in its charting of Klee's own course through the turbulent waters of modern art. Beginning with Klee's early interest in the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley, Jordan proceeds to discuss the influence of Goya ("Goya hovers around me," Klee wrote in 1906), the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, the Fauves, and, of course, the Cubists. The thought and works of Picasso, Braque, and particularly Delaunay, are carefully related to Klee's early works and writings, as are the theories of those German artists who first responded to the challenge of French Cubism and were to be known as the Blue Rider Group. Having set the stage, Jordan then begins a probing analysis of Klee's Cubist-related works, exploring and defining the structure of Klee's paintings, drawings, and prints with the precision of a geologist laying bare the stones and strata of a complex terrain.

I know of few studies of the formal evolution of a modern artist as scholarly and perceptive as this invaluable book, and Jordan's judicious choice of illustrations many of them fine color reproductions makes the work visually enlightening as well as arthistorically profound. Above all, the author handles his material with a combination of clarity and eloquence that will hold the attention of scholar and layman alike. Like Paul Klee, Jim Jordan has seen modern art from both sides that of the painter and that of the historian-critic and the affinity shows. He has given us a picture of Klee's art that is as rich and thoughtful as the works revealed to us in his book.

Clifton Olds '57 is Edith Cleaves BarryProfessor of the History and Criticism of Artat Bowdoin College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

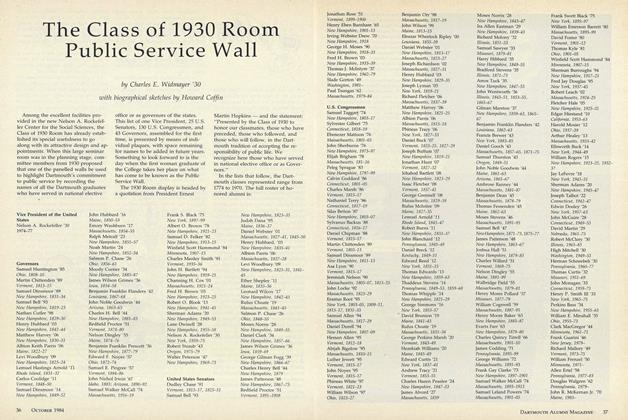

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

October 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Cover Story

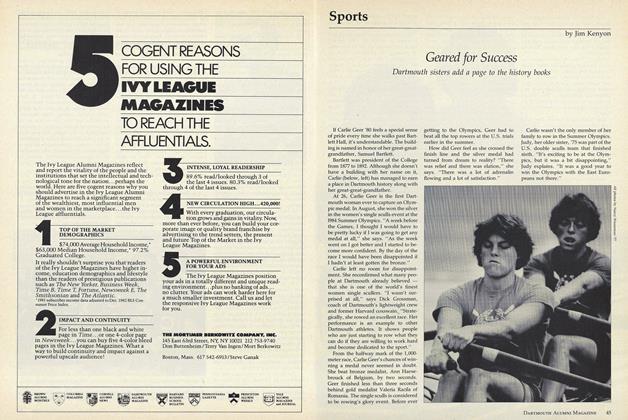

Cover StoryGeared for Success

October 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

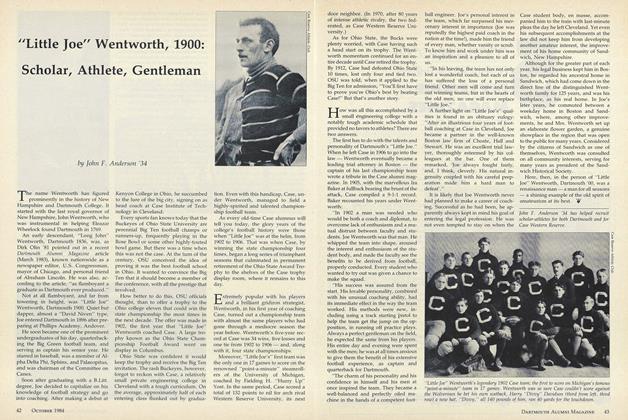

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

October 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

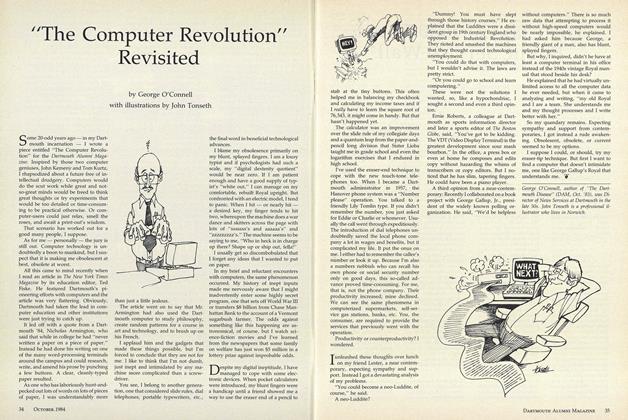

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

October 1984 By George O'Connell -

Article

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

October 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleGetting Better with Age

October 1984 By Gayle Gilman '85

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

July 1919 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MARCH 1973 -

Books

BooksA LAYMAN'S GUIDE TO NAVAL STRAT

October 1942 By Bruce Knight -

Books

BooksWar Administration of the Railways in the United States and Great Britain

July 1918 By C.A.P. -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN EAGLE.

February 1935 By Frederic P. Lord '98 -

Books

BooksTHE INTIMATE PROBLEMS OF WOMEN.

May 1954 By JOHN S. LYLE '34, M.D.