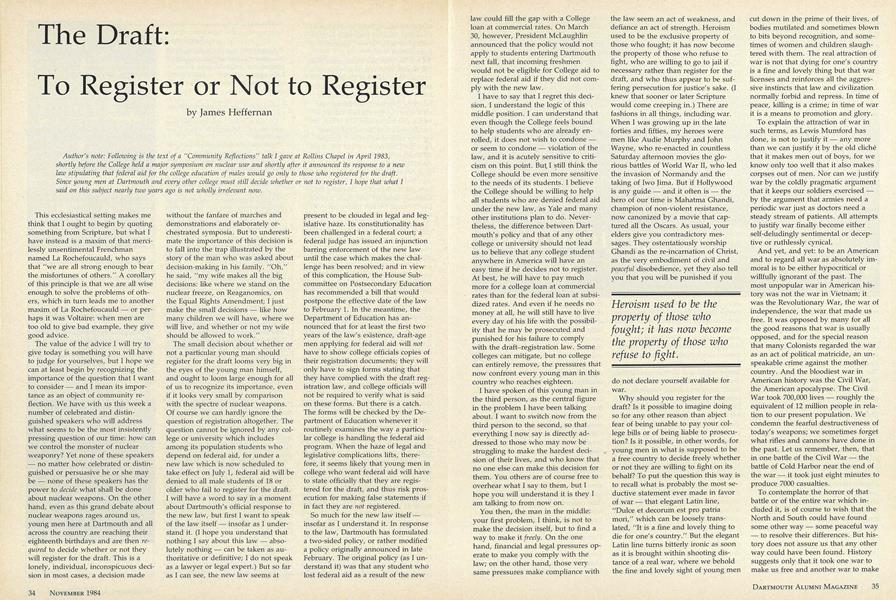

Author's note: Following is the text of a "Community Reflections" talk I gave at Rollins Chapel in April 1983, shortly before the College held a major symposium on nuclear war and shortly after it announced its response to a new law stipulating that federal aid for the college education of males would go only to those who registered for the draft. Since young men at Dartmouth and every other college must still decide whether or not to register, I hope that what I said on this subject nearly two years ago is not wholly irrelevant now.

This ecclesiastical setting makes me think that I ought to begin by quoting something from Scripture, but what I have instead is a maxim of that mercilessly unsentimental Frenchman named La Rochefoucauld, who says that "we are all strong enough to bear the misfortunes of others." A corollary of this principle is that we are all wise enough to solve the problems of others, which in turn leads me to another maxim of La Rochefoucauld or perhaps it was Voltaire: when men are too old to give bad example, they give good advice.

The value of the advice I will try to give today is something you will have to judge for yourselves, but I hope we can at least begin by recognizing the importance of the question that I want to consider and I mean its importance as an object of community reflection. We have with us this week a number of celebrated and distinguished speakers who will address what seems to be the most insistently pressing question of our time: how can we control the monster of nuclear weaponry? Yet none of these speakers no matter how celebrated or distinguished or persuasive he or she may be none of these speakers has the power to decide what shall be done about nuclear weapons. On the other hand, even as this grand debate about nuclear weapons rages around us, young men here at Dartmouth and all across the country are reaching their eighteenth birthdays and are then required to decide whether or not they will register for the draft. This is a lonely, individual, inconspicuous decision in most cases, a decision made without the fanfare of marches and demonstrations and elaborately orchestrated symposia. But to underestimate the importance of this decision is to fall into the trap illustrated by the story of the man who was asked about decision-making in his family. "Oh," he said, "my wife makes all the big decisions: like where we stand on the nuclear freeze, on Reaganomics, on the Equal Rights Amendment; I just make the small decisions like how many children we will have, where we will live, and whether or not my wife should be allowed to work."

The small decision about whether or not a particular young man should register for the draft looms very big in the eyes of the young man himself, and ought to loom large enough for all of us to recognize its importance, even if it looks very small by comparison with the spectre of nuclear weapons. Of course we can hardly ignore the question of registration altogether. The question cannot be ignored by any college or university which includes among its population students who depend on federal aid, for under a new law which is now scheduled to take effect on July I, federal aid will be denied to all male students of 18 or older who fail to register for the draft. I will have a word to say in a moment about Dartmouth's official response to the new law, but first I want to speak of the law itself insofar as I understand it. (I hope you understand that nothing I say about this law absolutely nothing can be taken as authoritative or definitive; I do not speak as a lawyer or legal expert.) But so far as I can see, the new law seems at present to be clouded in legal and legislative haze. Its constitutionality has been challenged in a federal court; a federal judge has issued an injunction barring enforcement of the new law until the case which makes the challenge has been resolved; and in view of this complication, the House Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education has recommended a bill that would postpone the effective date of the law to February 1. In the meantime, the Department of Education has announced that for at least the first two years of the law's existence, draft-age men applying for federal aid will not have to show college officials copies of their registration documents; they will only have to sign forms stating that they have complied with the draft registration law, and college officials will riot be required to verify what is said on these forms. But there is a catch. The forms will be checked by the Department of Education whenever it routinely examines the way a particular college is handling the federal aid program. When the haze of legal and legislative complications lifts, therefore, it seems likely that young men in college who want federal aid will have to state officially that they are registered for the draft, and thus risk prosecution for making false statements if in fact they are not registered.

So much for the new law itself insofar as I understand it. In response to the law, Dartmouth has formulated a two-sided policy, or rather modified a policy originally announced in late February. The original policy (as I understand it) was that any student who lost federal aid as a result of the new law could fill the gap with a College loan at commercial rates. On March 30, however, President McLaughlin announced that the policy would not apply to students entering Dartmouth next fall, that incoming freshmen would not be eligible for College aid to replace federal aid if they did not comply with the new law.

I have to say that I regret this decision. I understand the logic of this middle position. I can understand that even though the College feels bound to help students who are already enrolled, it does not wish to condone or seem to condone violation of the law, and it is acutely sensitive to criticism on this point. But I still think the College should be even more sensitive to the needs of its students. I believe the College should be willing to help all students who are denied federal aid under the new law, as Yale and many other institutions plan to do. Nevertheless, the difference between Dartmouth's policy and that of any other college or university should not lead us to believe that any college student anywhere in America will have an easy time if he decides not to register. At best, he will have to pay much more for a college loan at commercial rates than for the federal loan at subsidized rates. And even if he needs no money at all, he will still have to live every day of his life with the possibility that he may be prosecuted and punished for his failure to comply with the draft-registration law. Some colleges can mitigate, but no college can entirely remove, the pressures that now confront every young man in this country who reaches eighteen.

I have spoken of this young man in the third person, as the central figure in the problem I have been talking about. I want to switch now from the third person to the second, so that everything I now say is directly addressed to those who may now be struggling to make the hardest decision of their lives, and who know that no one else can make this decision for them. You others are of course free to overhear what I say to them, but I hope you will understand it is they I am talking to from now on.

You then, the man in the middle: your first problem, I think, is not to make the decision itself, but to find a way to make it freely. On the one hand, financial and legal pressures operate to make you comply with the law; on the other hand, those very same pressures make compliance with the law seem an act of weakness, and defiance an act of strength. Heroism used to be the exclusive property of those who fought; it has now become the property of those who refuse to fight, who are willing to go to jail if necessary rather than register for the draft, and who thus appear to be suffering persecution for justice's sake. (I knew that sooner or later Scripture would come creeping in.) There are fashions in all things, including war. When I was growing up in the late forties and fifties, my heroes were men like Audie Murphy and John Wayne, who re-enacted in countless Saturday afternoon movies the glorious battles of World War II, who led the invasion of Normandy and the taking of Iwo Jima. But if Hollywood is any guide and it often is the hero of our time is Mahatma Ghandi, champion of non-violent resistance, now canonized by a movie that captured all the Oscars. As usual, your elders give you contradictory messages. They ostentatiously worship Ghandi as the re-incarnation of Christ, as the very embodiment of civil and peaceful disobedience, yet they also tell you that you will be punished if you do not declare yourself available for war.

Why should you register for the draft? Is it possible to imagine doing so for any other reason than abject fear of being unable to pay your college bills or of being liable to prosecution? Is it possible, in other words, for young men in what is supposed to be a free country to decide freely whether or not they are willing to fight on its behalf? To put the question this way is to recall what is probably the most seductive statement ever made in favor of war that elegant Latin line, "Dulce at decorum est pro patria mori," which can be loosely translated, "It is a fine and lovely thing to die for one's country." But the elegant Latin line turns bitterly ironic as soon as it is brought within shooting distance of a real war, where we behold the fine and lovely sight of young men cut down in the prime of their lives, of bodies mutilated and sometimes blown to bits beyond recognition, and sometimes of women and children slaughtered with them. The real attraction of war is not that dying for one's country is a fine and lovely thing but that war licenses and reinforces all the aggressive instincts that law and civilization normally forbid and repress. In time of peace, killing is a crime; in time of war it is a means to promotion and glory.

To explain the attraction of war in such terms, as Lewis Mumford has done, is not to justify it any more than we can justify it by the old cliche that it makes men out of boys, for we know only too well that it also makes corpses out of men. Nor can we justify war by the coldly pragmatic argument that it keeps our soldiers exercised by the argument that armies need a periodic war just as doctors need a steady stream of patients. All attempts to justify war finally become either self-deludingly sentimental or deceptive or ruthlessly cynical.

And yet, and yet: to be an American and to regard all war as absolutely immoral is to be either hypocritical or willfully ignorant of the past. The most unpopular war in American history was not the war in Vietnam; it was the Revolutionary War, the war of independence, the war that made us free. It was opposed by many for all the good reasons that war is usually opposed, and for the special reason that many Colonists regarded the war as an act of political matricide, an unspeakable crime against the mother country. And the bloodiest war in American history was the Civil War, the American apocalypse. The Civil War took 700,000 lives roughly the equivalent of 12 million people in relation to our present population. We condemn the fearful destructiveness of today's weapons; we sometimes forget what rifles and cannons have done in the past. Let us remember, then, that in one battle of the Civil War the battle of Cold Harbor near the end of the war it took just eight minutes to produce 7000 casualties.

To contemplate the horror of that battle or of the entire war which included it, is of course to wish that the North and South could have found some other way some peaceful way to resolve their differences. But history does not assure us that any other way could have been found. History suggests only that it took one war to make us free and another war to make us united. In some deep and disturbing but ultimately undeniable sense, we are the beneficiaries of those two wars, and we cannot wish them away without wishing away at least some of the freedom and perhaps all of the union of these United States.

One can grant all that, of course, and still say that the state of the country and more importantly of the world has changed drastically in the 120 years since the time of the Civil War. It has changed drastically even since World War II, which is sometimes recalled as the last unequivocally "good" war, a war we bravely and confidently fought against an adversary who conveniently personified evil in its most diabolical form. We think back nostalgically to the heroic determination of Churchill, for instance, who roundly declared after the British were driven from Dunkirk that "we will never surrender." Yet it was Churchill who ordered the fire-bombing of Dresden, in which 130,000 men, women, and children were killed: a disaster memorably re-created by our present Montgomery Fellow in Slaughterhouse Five. And it was our own President Truman who ordered the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki an action so horrible that no sane person would wish to see it repeated, whatever the provocation.

You will want to know by now if you have not been wondering already what all this has to do with your decision about the draft, and where I stand on the question that you will finally have to answer for yourself. The reason I have no easy answer for this question is that war is an extraordinarily complicated phenomenon: ghastly to contemplate, but sometimes not so ghastly as the alternatives to it. If it is impossible to imagine anything ghastlier now than a nuclear war, we must also recognize that so-called "conventional" wars are still being fought, and so long as they constitute an alternative to nuclear war, we must be grateful for them, however grimly grateful. The day that this or any other country has nothing but nuclear weapons to fight with will not mean the end of war; it will far more likely mean the end of civilization. We will end all war only when we have found a way to sublimate all human aggression, and I honestly do not think that way will be found in my lifetime or yours.

Very well, you will say, conventional wars are still being fought and perhaps they are indeed inevitable in certain areas of the world: in the Middle East, in Afghanistan, in Latin America. But these are not our wars, you will say, and after the disaster of Vietnam, why should we consider even the possibility of drafting American men to fight in them? What possible purpose is served by the draft registration law?

To this question I have two answers One is that in spite of what we did in Vietnam, we cannot conclude that American troops bring nothing but disaster wherever they are sent. It was precisely a fear of repeating our protracted involvement in Vietnam that led the president to withdraw the Marines from Lebanon right after the PLO had been evacuated; yet it was this very withdrawal that led to a disaster. It was the absence of American troops that made it possible for Christian Falangists for those who called themselves Christian to enter the refugee camps of West Beirut and slaughter the Palestinians they found there. I don't think it is foolish to believe that the presence of American troops might well have prevented this disaster, and in spite of what has recently happened at the American embassy, the return of the Marines to Lebanon as part of a multi-national force has created at least the possibility that the Lebanese themselves may peacefully reposses their own country.

Am I suggesting, then, that you should allow yourself to be drafted so that you can play the role of international policeman? No, I am not. I am saying only that just as we cannot be sure that everything our government does is bound to be right, we cannot be sure that everything it does will be wrong. I do not now know any good reason for drafting American men, and I can see as well as you that the civil war in El Salvador would be the worst possible reason; but I am unwilling to state categorically that no good reason for a draft could ever arise. To register for the draft is to give the government what I believe it deserves: the benefit of the doubt.

Of course you may disagree. You may sharply disagree. You may believe that the government does not deserve the benefit of the doubt, that you could never support or participate in any military action that this country might choose to undertake. If you feel this way, and if you are ready to face additional debt, or at the very least the risk of prosecution for the sake of your beliefs, then I can say only that I respect the strength and sincerity of your conviction. But like the courage needed to face an enemy, the courage needed to resist the laws of one's own country is a limited resource, and should be spent carefully. The time to spend it, I think, is when and if the government drafts you to participate in a specific military action which you cannot support. Henry David Thoreau, the architect of civil disobedience and the spiritual ancestor of Ghandi and Martin Luther King, went to jail for refusing to pay a tax he believed would help support slavery and war. But Thoreau spent only one night in jail; he came out the next morning because someone else had paid the tax for him, and he saw no means of preventing that. For everything, says the Book of Ecclesiastes, "there is a season. ... a time to keep silence, and a time to speak; a time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace." In his classic essay on civil disobedience, Thoreau quietly declared war on the government, "after my own fashion," he said; but he did not say that every citizen should be perpetually at war with the government, or even that he himself expected to be. On the contrary, in words too often overlooked, Thoreau described the moral risk of civil disobedience, the moral of adopting it as a way of life. Civil disobedience "is my position at present" at a time when the United States was fighting Mexico in a war he opposed. "But," he added, "one cannot be too much on his guard in such a case, lest his action be biased by obstinacy, or an undue regard for the opinions of men. Let him see that he does only what belongs to himself and to the hour." For you at this hour I have no better advice than that. "W

Heroism used to be the property of those who fought; it has now become the property of those who refuse to fight.

...like the courage needed to face an enemy, the courage needed to resist the laws of one's own country is a limited resource, and should be spent carefully.

Prof. Heffeman, who received his Ph.D. from Princeton, came to Dartmouth in 1965. He was chairman of the Department of English from 1978 to 1981.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

November 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHamming It Up

November 1984 By Gay E. Milius, Jr. '33 and Dick Dorrance '36 -

Feature

FeatureGet a Job

November 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeaturePractice, practice, practice

November 1984 -

Books

BooksSo Much More

November 1984 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

November 1984 By Francis R. Drury Jr.

James Heffernan

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

FEATURE

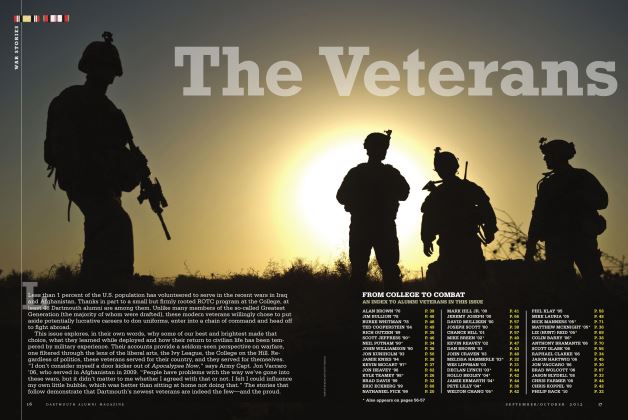

FEATUREThe Veterans

Sep - Oct By COMPILED BY LISA FURLONG -

Feature

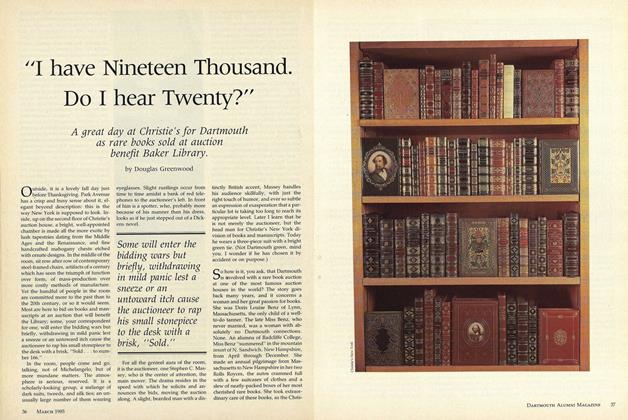

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

MARCH • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Feature

FeatureThe Vanishing Ability To Write

OCTOBER 1962 By George O’Connell -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN AN EASY BUCK WITH A CARD TRICK

Sept/Oct 2001 By MICHAEL ELLIS '39 -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75