Learning Curve

A professor emeritus recalls his early days of standing at a lectern with no idea what he was going to say.

July/August 2005 James HeffernanA professor emeritus recalls his early days of standing at a lectern with no idea what he was going to say.

July/August 2005 James HeffernanA professor emeritus recalls his early days of standing at a lectern with no idea what he was going to say.

DANTE BEGINS THE INFERNO BY TELLING us that in the middle of life's journeynelmezzo delcammin dinostra vita—he found himself lost in a dark wood. I know the feeling. In the middle of the spring term of 1966, near the end of my first year at Dartmouth as an assistant professor of English, I felt I was sinking into quicksand.

I was teaching two courses that term, as I had done in the fall and winter. (In the mid-19605, before year-round operation, we normally taught six courses in an academic year.) But those earlier classes had been small, powered mainly by discussion. With nearly 100 students, the course on English Romantic poetry that Ed been asked to teach with another assistant professor called for something I had never produced before: lectures. Nowadays, newcomers to the English department usually arrive with at least some lecturing experience. I had managed to get through graduate school without gaining any, and at Dartmouth I had run all my courses with ample help from the students, who were regularly asked to say something- anything—to help me fill up the class hour. Of course teachers can always throw out questions of their own in the midst of a lecture, but in a big class such questions are usually met with resounding silenceon the perfectly reasonable assumption that they are rhetorical pit stops meant only to rev up the engine of exposition for another lap around the track. Essentially, then, I was expected to talk nonstop for the better part of an hour, with perhaps a few minutes left for questions at the end.

I was on the mound in this way for every other class, a good deal more than usual for newcomers in the 19605. Typically, new members of the department at that time were paired with veterans in large courses and asked to give just a few lectures. But I was paired with another assistant professor, and we each took half of them. As a result, I spent much of class time babbling, flailing my arms to keep from sinking wholly into the sand and making as much noise as possible to fill the pedagogical void. We assigned so much poetry that we had barely time to read it ourselves, much less explore it effectively in class. In the middle of the term, when we gave an exam stuffed with questions that we had scarcely touched in our lectures, we nearly provoked a mutiny.

told me howwell the department had been placing its former members at other institutions. Only after stepping out of his office did I realize what he was telling me: My Dartmouth days were numbered. They were not quite up, though. The nice thing about a three-year contract is that for anything less than gross turpitude—as distinct from my gross ineptitude—you can't be sacked after just one year. But this hardly meant that I could coast to tenure; it meant only that I had another year or so to learn how to lecture. Along with the bum's rush cordially proffered by the chair, the experience of lecturing for the first time taught me a simple lesson: I could never do it well without a lot more work.

Fortunately, my second year at Dartmouth gave me time to prepare a lecture in a course team-taught by senior as well as junior members of the department. The senior members included one of the best lecturers I've ever heard: Bob Hunter. Talking about Shakespeare's The Tempest, Hunter took his point of departure from the one-man Chorus in Henry V, who bids us visualize all the events that words can evoke, to "piece out our imperfecmerely tions with your thoughts." The idea that even Shakespeare could fall short of perfection, that even he needed our imaginations to make his plays work, was merely the first of a series of provocative points that Hunter made with captivating wit and dramatic force. Quoting the Chorus' apology for "the flat unraised spirits" that dared to re-create a battlefield on a stage, he reminded us that Shakespeare's women were all originally played by boys—"flat unraised spirits" indeed! Talking of political usurpation in TheTempest, he pointed straight to the moment when Antonio—the usurping duke of Milan—goads Sebastian to kill his sleeping brother Alonso so as to gain the throne of Naples. (Alonso doesn't actually get killed, but that's another matter.) Hunter knew how to seize hold the attention of the class, and as I listened I realized fully—for the first time—that good lecturing is a performing art. Like any other performing art, it calls for study of those who are good at it, extensive preparation, and plenty of practice.

For the team-taught course I was asked to give just one lecture—on Emily Bronte's Withering Heights. Writing it out in full (I've never learned how to lecture well from notes), I developed a fairly simple idea: The irrepressible passion of Heath cliff and Catherine can never be contained or regulated, even after they die, by the order and conventions of the civilized world that surrounds them. It was a fairly simple approach to the novel, but the passion of its central characters drove my argument along, and I managed to carry the class with me. Afterwards, a sophomore—God bless him—told me it was the best lecture he had ever heard (though I don't think he'd yet heard many). I thus discovered that lecturing was something I could learn to do.

But of course it took a lot more learning and listening to do it well. Besides Hunter, the other great powerhouse in the English department during most of my Dartmouth years was Jim Cox. No one could crack up an audience the way Cox did, but more to the point, no one could better crack open a work of literature. His special force as a teacher sprang from his capacity to imagine the feelings of the reader at crucial points in a narrative. He never simply explained what the work meant; he caught us leaping to conclusions, as we do in Huckleberry Finn when Huck decides that he will "go to hell" rather than reporting on a runaway slave. Of course, Cox would say, you want to assure Huck that he will go straight to heaven for helping the runaway gain his freedom. But then Cox would show how the ending of the novel detonates that sentimental inference by turning the enterprise of liberation into a boy s cruel joke on a man who has already been freed.

I learned a lot from studying great lecturers at work, but some of the more important things I learned came from listening to my students. One afternoon during my very first year in teaching (as an instructor at the University of Virginia, where I taught for two years before coming to Dartmouth), I was struggling to lead about 30 students through Milton's Samson Agonistes—not exactly a picnic on the beach. Near the end of the class—my third of the day, and it ran for 75 minutes- I was running on empty when a student asked why it mattered so much that Samson pulled down the temple. As I started to say something halfway plausible, a hand shot up in the back of the room and I had the good sense to call on its owner. Vigorously explaining how Samson took down all the Philistine leaders along with the temple itself, he hit the question right out of the park, and thus taught me a crucial lesson: Always give students the first crack at each others questions.

In the midst of a lecture, it can be hard to make room for any questions at all. But course evaluations give every student a chance to grade the lecturer, and when several students complained one year that I was reading my lectures, I knew I had to work harder to make them sound improvised. The bane of classrooms and academic conferences alike is the mechanically "read" paper, the oral transmission of something written for the page alone. What's written for the ear must be pungent, artfully repetitive (not all repetition is bad!), often interrogative and regularly punctuated by short, pithy sentences that encapsulate a central point. (Sample: While the scientist says, "it is," a Romantic poet such as William Blake declares, "I am")

Lecturing well, I have learned, means not simply explaining a work of literature but getting inside the head of a student meeting it for the first time. This doesn't mean vulgarizing, oversimplifying or dumbing anything down. It means anticipating the kinds of questions—and the kinds of resistance—that a given work may provoke. Yeats once wrote that we make rhetoric out of our quarrels with others but poetry from our quarrels with ourselves. Good lecturers on literature strive, I think, not so much to make speeches as to stage a running dialogue between themselves and first-time readers bursting with their first impressions. Years ago, lecturing for the first time on Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles, I foolishly assumed I could quickly settle a thorny question—is the heroine raped or seduced?—before moving on to what I thought were more important points. In the days before coeducation, a classful of men might have let that assumption pass. But the women in this class would not. For them no question raised by the novel trumps the importance of how Tess loser her virginity. Though I still believe that she is seduced, I soon realized that I could never again talk about this novel without carefully discussing why any readermale or female—might think otherwise.

I taught English at Dartmouth for 39 years—a bit longer than Arthur Jensen once anticipated. (He also failed to foresee that I would inherit both his office and his chair.) Afew years ago I was asked to record 24 lectures on James Joyces Ulysses for the the Teaching Company, which markets lectures on various academic topics to the general public via CD, DVD and videotape. The company liked the Joyce lectures well enough to ask for a second helping: 24 lectures on great authors from Wordsworth to Samuel Beckett. I could never have generated these lectures without the experience I gained at Dartmouth, which gave me the time and the means to crawl up out of the quicksand and learn my trade.

The experience of lecturing for the first time taught me a simple lesson: I could never do it well without a lot more work.

JAMES HEFFERNAN is aprofessor of Englishemeritus. His latest book—forthcoming in2006—is Cultivating Picturacy: Visual Art and Verbal Interventions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

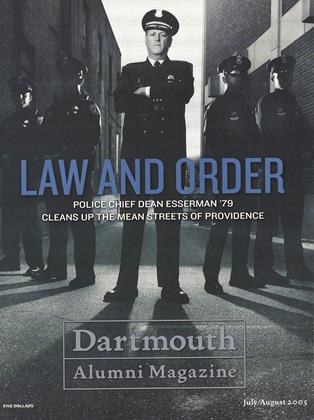

Cover Story

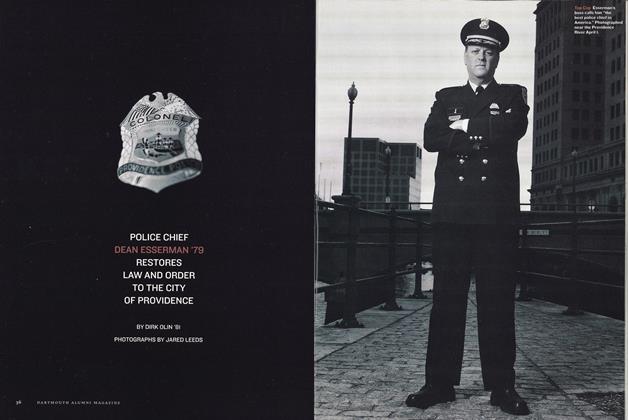

Cover StoryPolice Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence

July | August 2005 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureMud, Madras and Madness!

July | August 2005 By Gina Barreca ’79 -

Feature

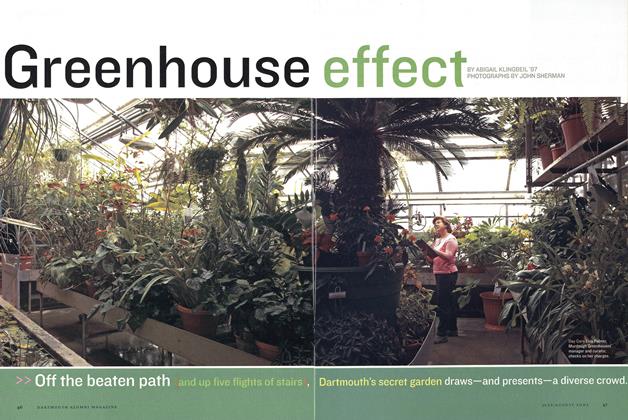

FeatureGreenhouse Effect

July | August 2005 By ABIGAIL KLINGBEIL ’97 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2005 By Thomas Vieth '80 -

Sports

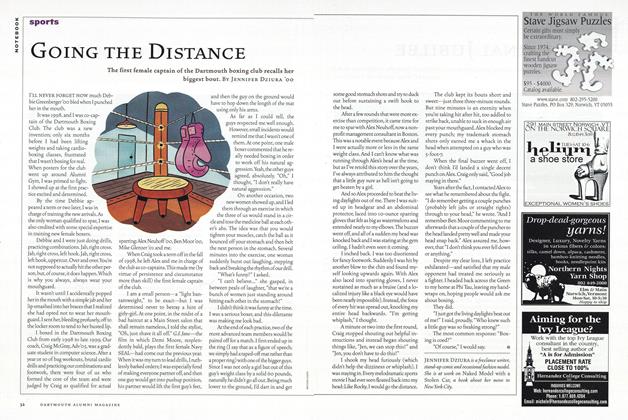

SportsGoing the Distance

July | August 2005 By Jennifer Dziura ’00

James Heffernan

FACULTY

-

Faculty

FacultySubject Matter

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 -

FACULTY

FACULTYSeeing and Believing

Nov/Dec 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

FACULTY

FACULTYOut of the Ordinary

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By LAUREN VESPOLI '13 -

FACULTY

FACULTYMore than a Game

Mar/Apr 2005 By Lauren Zeranski ’02 -

FACULTY

FACULTYPoetic Justice

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

FACULTY

FACULTYThe Truth Is Out There

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14