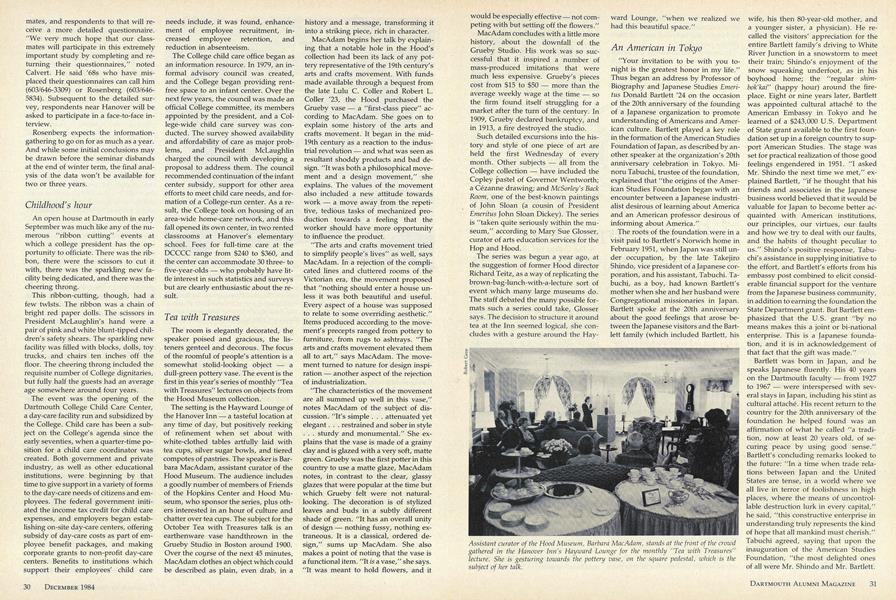

The room is elegantly decorated, the speaker poised and gracious, the listeners genteel and decorous. The focus of the roomful of people's attention is a somewhat stolid looking object a dull green pottery vase. The event is the first in this year's series of monthly "Tea with Treasures" lectures on objects from the Hood Museum collection.

The setting is the Hayward Lounge of the Hanover Inn a tasteful location at any time of day, but positively reeking of refinement when set about with white-clothed tables artfully laid with tea cups, silver sugar bowls, and tiered compotes of pastries. The speaker is Barbara MacAdam, assistant curator of the Hood Museum. The audience includes a goodly number of members of Friends of the Hopkins Center and Hood Museum, who sponsor the series, plus others interested in an hour of culture and chatter over tea cups. The subject for the October Tea with Treasures talk is an earthenware vase handthrown in the Grueby Studio in Boston around 1900. Over the course of the next 45 minutes, MacAdam clothes an object which could be described as plain, even drab, in a history and a message, transforming it into a striking piece, rich in character.

MacAdam begins her talk by explaining that a notable hole in the Hood's collection had been its lack of any pottery representative of the 19th century's arts and crafts movement. With funds made available through a bequest from the late Lulu C. Coller and Robert L. Coller '23, the Hood purchased the Grueby vase a "first class piece" according to Mac Adam. She goes on to explain some history of the arts and crafts movement. It began in the mid19th century as a reaction to the industrial revolution and what was seen as resultant shoddy products and bad design. "It was both a philosophical movement and a design movement," she explains. The values of the movement also included a new attitude towards work a move away from the repetitive, tedious tasks of mechanized production towards a feeling that the worker should have more opportunity to influence the product.

"The arts and crafts movement tried to simplify people's lives" as well, says Mac Adam. In a rejection of the complicated lines and cluttered rooms of the Victorian era, the movement proposed that "nothing should enter a house unless it was both beautiful and useful. Every aspect of a house was supposed to relate to some overriding aesthetic." Items produced according to the movement's precepts ranged from pottery to furniture, from rugs to ashtrays. "The arts and crafts movement elevated them all to art," says Mac Adam. The movement turned to nature for design inspiration another aspect of the rejection of industrialization.

"The characteristics of the movement are all summed up well in this vase," notes Mac Adam of the subject of discussion. "It's simple . . . attenuated yet elegant. . . restrained and sober in style . . . sturdy and monumental." She explains that the vase is made of a grainy clay and is glazed with a very soft, matte green. Grueby was the first potter in this country to use a matte glaze, MacAdam notes, in contrast to the clear, glassy glazes that were popular at the time but which Grueby felt were not naturallooking. The decoration is of stylized leaves and buds in a subtly different shade of green. "It has an overall unity of design nothing fussy, nothing extraneous. It is a classical, ordered design," sums up Mac Adam. She also makes a point of noting that the vase is a functional item. "It is a vase," she says. "It was meant to hold flowers, and it would be especially effective not competing with but setting off the flowers."

MacAdam concludes with a little more history, about the downfall of the Grueby Studio. His work was so successful that it inspired a number of mass produced imitations that were much less expensive. Grueby's pieces cost from $15 to $50 more than the average weekly wage at the time so the firm found itself struggling for a market after the turn of the century. In 1909, Grueby declared bankruptcy, and in 1913, a fire destroyed the studio.

Such detailed excursions into the history and style of one piece of art are held the first Wednesday of every month. Other subjects all from the College collection have included the Copley pastel of Governor Wentworth; a Cezanne drawing; and Mcsorley's BackRoom, one of the best known paintings of John Sloan (a cousin of President Emeritus John Sloan Dickey). The series is "taken quite seriously within the museum," according to Mary Sue Glosser, curator of arts education services for the Hop and Hood.

The series was begun a year ago, at the suggestion of former Hood director Richard Teitz, as a way of replicating the brown bag lunch with a lecture sort of event which many large museums do. The staff debated the many possible formats such a series could take, Glosser says.The decision to structure it around tea at the Inn seemed logical, she concludes with a gesture around the Hay ward Lounge, "when we realized we had this beautiful space."

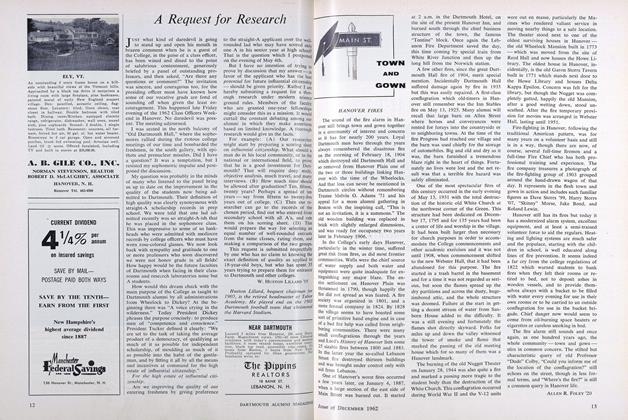

Assistant curator of the Hood Museum, Barbara Mac Adam, stands at the front of the crowdgathered in the Hanover Inn's Hayward Lounge for the monthly "Tea with Treasures"lecture. She is gesturing towards the pottery vase, on the square pedestal, which is thesubject of her talk.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe College Today

December 1984 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth Hall (1784-1984) A Bicentennial Tribute

December 1984 By Charlotte K. Younger -

Feature

FeatureChronicling the DOC

December 1984 By David O. Hooke '84 -

Feature

FeatureHanover's Bests

December 1984 -

Article

ArticleLover of parades

December 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1984 By Richard J. Goulder