"The money is staggering," says medieval historian Andrew Lewis '65, recipient of one of this year's 22 MacArthur Fellowships. Lewis learned on February 14 that he has been awarded $204,000 over the next five years. No strings attached.

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation was activated in 1978, on the death of John MacArthur, whose firm, Bankers Life and Casualty Company, was at the time the largest privately-held insurance company in the nation. The fellows program is unique in funding talented people personally rather than for projects.

"After you recover from the shock of the sum/' says Lewis, "you understand that it's also unrestricted money. I don't know of another award that's comparable." The program relies for candidates on some 100 anonymous nominators around the country, who come from many walks of life. Nominees are voted on by a 15-member selection committee, and then the awardwinners are telephoned out of the blue with the good news.

Lewis, who admits to being stunned by his call, says he never doubted its reality. "It was too obscure to be a prank," he recalls. "I had read a couple of sentences somewhere about the fellowship, but of course it didn't apply to me."

Lewis had more reason than some to be stunned. One of many victims of the academic job crunch of the seventies, Lewis, as he decribes it, went from pillar to post for years just staying afloat in academe. Unable to find a job as he was completing his doctorate at Harvard in 1972, he postponed taking the degree a year so as to qualify for a teaching fellowship that was not available to people with doctorates. The second year, at the end of June, he landed a visiting assistant professorship on the East Coast. Year three produced only an offer, made in August, to work as a bibliographer in a library on the West Coast. The next year he found a visiting lectureship for a year in Canada. At the beginning of the following September, he was offered a one-year position teaching Western Civilization in the Midwest. The year after that, 1977, he finally came to roost in a tenure-track position teaching history (mostly Western Civilization) at Southwest Missouri State University, where he is currently associate professor of history.

Despite being "almost driven out" of the profession by acute worry about employment, Lewis managed to glean enough time and energy from teaching, worrying, and moving to put together from his graduate school research a 356-page book about the French royal dynasty founded in 987 by Hugh Capet. Harvard University Press published it in 1982, and then the tide turned a little for Lewis. RoyalSuccession in Capetian Fiance caught the delighted attention of eminent French historian Georges Duby, who declared in reviewing it that its author was "among the best medievalists of his generation."

"It is pathbreaking work," says Dartmouth Professor of History Charles Wood, who acted as one of the young scholar's mentors during his undergraduate days. "It's a book about the sociology of rulership and property. On the one hand, rulership is an abstraction, and on the other, it is a family enterprise. The toughest thing in any political system is the transference of power from one human being to another, and Andy's book explores what forces bear on that."

"My aim" Lewis explains, "was to situate the monarchy in the context of its society, in contrast to earlier national history, which tends to treat the crown and kings as a world apart. The structure and organization of the royal family is revealed through successions to offices and land, and if you compare these to similar practices among the nobility, you find they are substantially the same. Kings, in fact, patterned their behavior on that of nobles. Kings do not emerge as setting patterns."

Lewis, who was recently asked to lecture at Harvard, is described byWood as "loving and being dedicated to precision in dealing with manuscripts, many of which are nearly impossible to read." Such careful scholarship as Lewis practices, Wood explains, is rare. Lewis himself decribes working with ancient manuscripts as both difficult and mysterious: "The originals of the 11th and 12th centuries are good carefully and clearly inscribed, a pleasure to work with. But when the original is lost and you have to use a later copy, the handwriting is awful. From the 15th century on, scribes used a fluent cursive, and their scrolls are often worse than student lecture notes nightmarish. How do you deal with it? Slowly. You struggle through such a manuscript once, without much result, and try again a week later. Somehow, the second time, you usually make some headway. I've tried to figure out what the headway is based on, and I can't."

The MacArthur award, says Lewis, has come just in time: "The Harvard lecture used up the last of my graduate-school notes." He will now have time to pick up research again. Sticking with the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries, he plans to study the nobility of north and north-central France. He will continue to teach, but only part-time. After doing a good deal of microfilm spadework in this country, primarily at Harvard's Widener Library, Lewis will study original sources in France, mostly in Paris, where Napoleon concentrated most of France's archives.

"Andy is so damn good," says Wood, "and he has been caught at a place without a good library, teaching a 12-hour load. It would have been the death of him as a scholar. Now, with five years of virtually no teaching, he is liberated. And the award is incontrovertible proof of the quality of his work. It's nice that he has been recognized at last."

Merlin the Magician was this year's center-of-the-Green snow sculpture, highlighting the "Camelot Frozen in Time"Winter Carnival theme. Although hismagic wand couldn't fend off weekendlong rains, Merlin was able to conjure upthe ski team's first Carnival win since1975.

The first day of spring was ushered in by a big snow storm which has kept the snow plow busy all day around the Hanover streets. . . . But we never consider it spring in Hanover until after the Easter vacation." Douglas VanderHoof '01, in a letter dated March 1, 1900

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

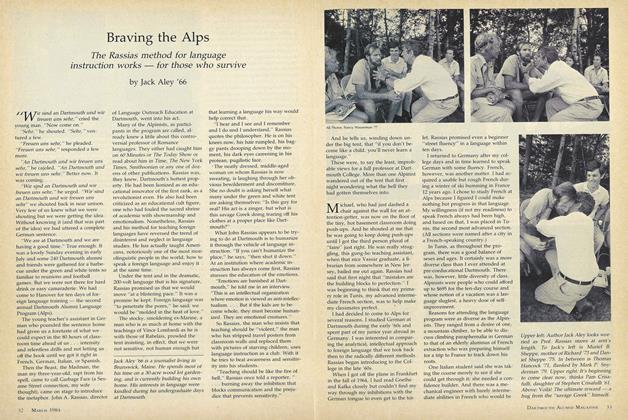

FeatureBraving the Alps

March 1984 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Public Policy: The Washington Internship Program

March 1984 By Frank Smallwood '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

March 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

FeatureThose Championship Seasons

March 1984 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Art

March 1984 By Monica Louise Latini '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

March 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower